Journal of Education, Humanities, Management and Social Sciences (JEHMSS), Vol. 2, No. 2, March 2024. https://klamidas.com/jehmss-v2n2-2024-02/ |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Fuel Subsidy Removal and the Agony of the Deprived in Nigeria Livinus Nwaugha & Ihezie Solomon Okekwe

Abstract Increase in the price of premium motor spirit (PMS) has always been a source of panic to the average Nigerian as it usually has a multiplier and inflationary effect that reduces the purchasing power of most Nigerians, especially the poor. A major reason for the concern is that most vehicles used in transporting commuters, goods and services in Nigeria are PMS-powered, and any increase in the price of PMS (petrol) directly and immediately translates to increase in the price of virtually all commodities and services. To limit the ripple effects of PMS price increase, government after government in Nigeria had been exercising control over how much consumers were asked to pay for PMS at the filling stations. Since the 1977 price control act, the federal government had been fixing the price of PMS to prevent the forces of demand and supply from swaying inordinately against consumers. However, owing to the massive corruption that characterized government’s subsidization of PMS, and the attendant financial losses borne by government over the years, President Bola Ahmed Tinubu, in his inauguration speech on May 29, 2023, announced the removal of fuel subsidy, thereby provoking a nationwide outcry against the decision. This paper examines fuel subsidy removal and the agony of the deprived in Nigeria as well as the history of fuel price increases in Nigeria. The paper examines vital issues connected with fuel subsidy in Nigeria. A mixed method of data collection was adopted for the paper: relevant data were obtained from 30 respondents who were purposively selected and interviewed while other data were sourced from extant literature. The paper revealed that putting an end to oil subsidy so that the forces of demand and supply would be determining the price of PMS is not a bad policy but that government should have put in place remedial measures to cushion the effect of the subsidy removal on the masses. Keywords: fuel subsidy removal, agony, deprived, corruption, government

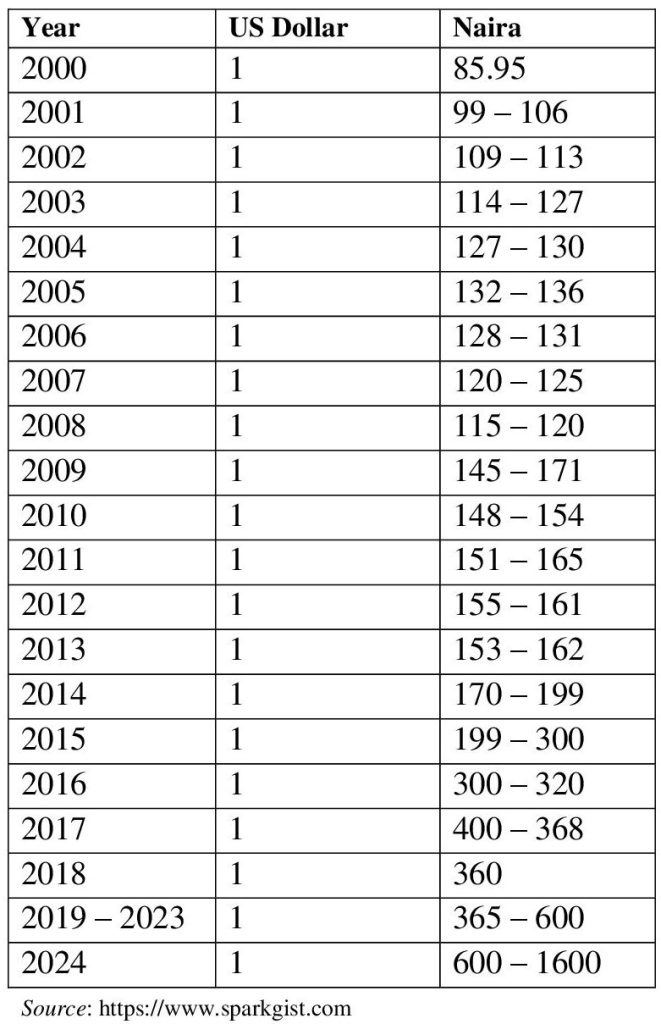

Introduction Nigeria is a nation blessed with human and natural resources. Its diverse but fertile soil types are ideal for the production of various kinds of farm produce, including highly-demanded cash crops. Its climatic and topographic diversity makes it very suitable for other forms of agricultural endeavours, such as the breeding of livestock and fishing, and for agro-based ventures, such as hides and skin processing. Nigeria’s stockpile of mineral resources includes, among several others, petroleum, gas, limestone, tin and iron ore. Before independence in 1960, Nigeria was reputed as a major exporter of cocoa, palm oil, groundnut, millet and cotton, and these, together with tin, constituted its major foreign-exchange earners (Akindele, 1988:103). This was the period adequate attention was paid to agriculture. The then regions, Northern, Western and Eastern regions, were distinctly marked and known by their agricultural output. The Northern region was the major producer of groundnut, millet, pepper, maize and cattle. Cocoa was the Western region’s cash crop, and through its cultivation the Western region was able to drive its economic development and growth; it built the impressive Cocoa House and the first television station in sub-Saharan Africa. The Eastern region was the major cultivator of palm oil and through it initiated several developmental projects in the region. In 1956 crude oil was discovered in large quantities at Olobiri in south-southern Nigeria, but became prominent as a major foreign-exchange earner in the 1970s. Before the 1970s agriculture was Nigeria’s main foreign revenue earner (Akindele, 1988). According to Atemie (1996), agriculture constituted 73% of Nigeria’s foreign-exchange earnings. But by the 1970s, Nigeria’s oil sector had taken the center stage as the mainstay of the economy, giving rise to the oil boom that characterized that petro-dollar economy (Akindele, 1988:113). The emergence of the petro-dollar economy disrupted and distorted Nigeria’s agricultural economy (Adubi, 2004). During the oil boom era, the naira was among the world’s strongest currencies; from the 1970s to the early 1980s, one US dollar exchanged for less than one naira. This exchange rate advantage could not last because Nigerians abandoned agriculture in search of oil-boom contracts, jobs and mercantile ventures. Along with that, Nigeria embarked upon massive importation of goods, many of which could have been locally produced; in no time Nigeria became one of the world’s largest importers of wheat, rice, household products, cosmetics, clothing materials, and diverse vehicles and generators, to name but a few. As Nigeria was importing almost everything while exporting virtually nothing else but crude oil, undue pressure was put on Nigeria’s foreign exchange earnings. This situation was not helped by Nigeria’s indebtedness to foreign financial institutions and organisations who ultimately pressurized it into adopting, in the mid 1980s, the structural adjustment programme (SAP) that ultimately led to the devaluation of the naira against major Western currencies, principally the US dollar. Overview of Naira’s Exchange-Rate Oscillations The devaluation of the naira signaled a distortion in the economy and a general fall in the living standard of Nigerians, a situation which was exacerbated by increase in the rate of unemployment and the rate of violent crime. All of these were aggravated by systemic maladministration and corruption at federal, state and local government levels. The international angle to naira’s devaluation was and remains the fact that oil is mostly bought and exchanged in US dollar, so any variation in the value of the US dollar automatically impacted on the price of oil in the international market. In spite of this, Nigeria’s bad domestic economic policies should be largely blamed for the country’s economic woes, including the continuous devaluation of the naira since the 1980s. For example, according to sparkgist.com, by 1986 one US dollar was equal to 90 kobo but as at 1997 one dollar was equal to ₦105. As at February 2024, more than ₦1,500 was exchanged for one US dollar at the black market. Exchange rate in the international market is subject to constant fluctuations; this is why many countries fix the exchange rate of their local currencies against the world’s major currencies for basic economic reasons (Jhingan, 2009). The exchange rate of a country’s currency vis-à-vis major currencies, like Euro, pounds sterling, and the Japanese Yen, plays a great role in stabilizing its economy. Hence, nations have continued to make policies that strengthen their currencies; despite these policies, currency exchange rates fluctuate in the international market as the value of the US dollar, the overriding currency of international transactions, increases or decreases (Jhingan, 2009). Factors that are responsible for exchange rate oscillation can be broadly grouped into two: internal and external factors. The internal factors occur when a country, through its deliberate economic policy, decides to lower its exchange rate in the form of devaluation in order to make its commodities in the international market cheaper than other countries’ commodities; comparative considerations could also make a country increase the value of its currency. External factors come into play when the exchange rate rise or fall is caused by global economic conditions, such as recession or global instability caused by, for instance, war or outbreak of a devastating pandemic. The importance of the US dollar to Nigeria’s economy cannot be overemphasized. Nigeria’s major export commodities are valued in the international market in USD, and most times Nigerians seem to believe that they do not have any direct influence on the fluctuation of NGN-USD rate. This may not be totally true. For example, when the naira was introduced on January 1, 1973, to replace the Nigerian pound, £1 = ₦2, according to CBN records. At that time the Nigerian economy was stable, the decline of Nigeria’s agricultural sector had started but many were still into farming, and Nigeria was not an indebted country. When Nigerians, especially the youth, largely abandoned agriculture in subsequent years and migrated to the cities in search of greener pastures, the country became almost totally reliant on oil. There was a notable energy crisis which affected the fortunes of Oil Producing and Exporting Countries (OPEC), one of which was Nigeria. Overwhelmed by many elephant projects and programmes, one of which was FESTAC ’77 extravaganza, Nigeria began to borrow from the International Monetary Fund (IMF); by the 1980s, Nigeria had become one of the world’s most indebted countries, a status which forced it to adopt SAP in 1986. The decline of the Nigerian economy led to the decline of the naira. By 1999, when Nigeria’s current democratic dispensation began, $1 = ₦85.95. While we may blame the military for mismanaging the Nigerian economy, and consequently the naira, the table below, which captures the dwindling fortunes of the naira under the watch of civilian politicians, indicates that Nigerian leaders, both military and civilian, have proved to be incapable of solving Nigeria’s economic problems. Below is a table which captured the slide of the naira from the year 2000 to 2024. The data provided in the table are authentic as they are similar to those stated in an independent table published in Twitter by Abubakar (2024). Table 1: Dollar-Naira Exchange Rates from 2000 to 2024

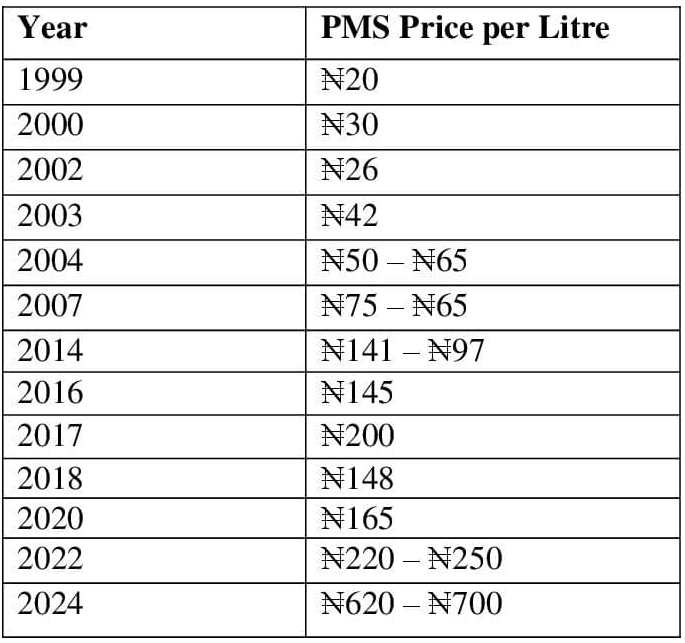

Nigeria’s Oil Production and Refining Woes Between 1978 and 1989, Nigeria established three refineries in Port Harcourt, Warri and Kaduna to make oil accessible and available to the local market as well as for export (nigeriatradehub 2024). These refineries were the drivers of the oil economy in Nigeria from the late 1970s to 2002. When the Port Harcourt refinery was completed, it had a capacity of 100,000 Bpsd; Warri refinery was completed and commissioned in 1978 with a production capacity of 100,000 Bpsd. Also in 1980, Kaduna refinery was completed and commissioned with production capacity of 50,000 Bpsd (Oaikhena, 2004). By 2002, as investment in agriculture further declined, Nigeria’s oil industry provided 98% of the country’s foreign exchange earnings. Through this singular indicator Nigeria became a mono economy. In the 1990s, during the military era, oil production capacity declined as a result of poor governance, pipeline vandalisation and upsurge of resource control issues. This continued even after the return to democratic rule in 1999. By 2002, pipeline vandalisation and kidnapping (to extort ransom) had become the order of the day in the Niger Delta region. The militancy degenerated to a war-like situation following the execution of Ken Saro-Wiwa and eight Ogoni activists by the Abacha administration in 1995. The Niger Delta, in spite of being the region where the bulk of Nigeria’s oil is extracted, has continued to experience environmental degradation and abject poverty caused mainly by the multinational oil companies, especially Shell BP, operating there. It was the abysmal state of the region that ignited the spirit of militancy which drew the attention of the government and the international community to the plight of the people of the region. The region’s different militant groups include Egbesu Boys, Niger Delta Volunteer Force and Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND), to mention but a few (CEDCOMS, 2003). The activities of these militant groups, at a point, nearly crippled the Nigerian economy as oil production reduced from 2.2 million barrels per day to 700,000 barrel per day in 2007. Even as at February 2024, due partly to the activities of militants, Nigeria’s average daily crude oil production dropped to 1.32 million barrels per day (bpd). This amounted to 105,000 bpd or 7.36 percent decrease from the 1.42 million bpd recorded in January 2024 (thecable.ng, 2024). Chronicle of Fuel Price Increases and their Ripple Effects in Nigeria The price of PMS has always been a source of concern to the average Nigerian as its increase or decrease has multiplier effects that affect the economic wellbeing of the citizens (Umoru, 2022). The reason is that most of the transportation system in Nigeria depends largely on PMS to power their vehicles, and any increase in PMS gives rise to increases in the prices of other commodities, including the prices of foodstuff and essential items that the poor and the under-privileged mostly depend on. This is why PMS price increases aggravate the condition of the downtrodden and increase the poverty level of the masses (Umoru, 2022:34). Below is a table of PMS price increases from 1999 to 2024. Table 2: The Changing Prices of PMS from 1999 to 2024

Sources: Zaccheaus Tunde Egbewole , Bolaji Aluko, Ike Okwuobi, and Umoru To show how an increase in PMS price affects the prices of other commodities in the market in Nigeria, let us see how the prices of two common food items (rice and bread) changed each time the price of PMS (as reflected in the above table) changed between 2014 to 2024. In 2014, when the price of PMS was ₦97 (there was a brief period of subsidy removal that shut up the price of PMS to ₦141 before a series of demonstrations forced back the price to ₦97), the price of a bag of rice ranged from ₦7000 to ₦8000 while a loaf of family-size bread cost ₦450. By 2016 to 2017, when the price of PMS was between ₦145 to ₦200, the price of a bag of rice was ₦39,000 to ₦40,000 while a loaf of family-size bread cost ₦750. Also by 2023 to 2024, when the price of PMS was ₦620 to ₦700, a bag of rice was sold between ₦50,000 to ₦75,000 while family-size bread cost ₦1000 to ₦1400. So, there is no doubt that an increase in PMS price influences the price of other commodities in the country. History of Fuel Subsidy Removal in Nigeria Fuel subsidy removal is a deliberate government policy to allow the forces of demand and supply determine the price of petroleum products in the market. However, the removal of fuel subsidy is a violation of 1977 Price Control Act (PCA) that mandates government to fix price of certain commodities in Nigeria, including petroleum products. The aim of fuel subsidy removal is to deregulate the price of fuel (PMS), especially as government can no longer cushion the effect of fuel subsidy now that it is faced with dire economic disequilibrium and paucity of funds caused by endemic corruption, racketeering and lack of transparency that characterized fuel subsidy management in Nigeria since the 1970s. Moves to remove fuel subsidy in Nigeria date back to 1988 when Nigeria was faced with dire economic crisis that led to the devaluation of the naira and other economic liberalization measures. However, all the earlier moves to remove fuel subsidy could not materialize as a result of opposition from the labour unions and civil society gtoups in Nigeria. A major move to remove fuel subsidy was made in 2012 by President Goodluck Jonathan who introduced SURE-P to help cushion the suffering the removal of fuel subsidy might cause the masses. SURE-P was a conscious government effort to re-inject the resources previously injected into fuel subsidy to other critical areas of the economy that would impact positively on the lives of the people. Government felt that the fraud that marked the fuel subsidy regime was endemic and that, if left unchecked, it might cripple the economy, especially as major oil marketers were engaged in diversion of petroleum products. It was to contain this market racketeering and diversion that President Jonathan assured Nigerians that with the removal of fuel subsidy other economic sectors would have enough fund that would create employment and reduce poverty –one of the cardinal objectives of Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). But the move to remove fuel subsidy was vehemently opposed by opposition parties and civil society groups. They said the move was sinister and anti-people, if not a total scam, and supported nationwide ‘occupy Nigeria’ protesters who besieged public places and government establishments. In 2016, the Buhari administration cited endemic corruption and market racketeering as some of the reasons which might necessitate the removal of fuel subsidy; for lack of political will the regime dilly-dallied until May 29th 2023 when it handed power to Bola Ahmed Tinubu as president. During his inauguration as the 16th president of Nigeria on May 29, 2023, President Ahmed Bola Tinubu bade farewell to fuel subsidy with his famous ‘fuel subsidy is gone mantra’ statement. He regarded fuel subsidy as a cankerworm that had eaten deep into the fabric of the economic fortune of Nigeria, something that must go if there must be any tangible forward leap for Nigeria’s transformation. The president adumbrated that Nigeria spent over 12 billion naira every year on fuel subsidy servicing, and said that no economy can develop that way. According to him, as cited in Sobowale (2023): Fuel subsidy payment were being funneled into the deep pockets and lavish bank accounts of selected group of individuals. This group had amassed so much wealth and power that they become a serious threat to the fairness of our economy and the integrity of our democratic governance. Nigeria could never become the society it was intended to be as long as such small powerful yet unelected group hold enormous influence over our political economy and the institution that govern it. Some fuel subsidy removal protagonists argue that fuel subsidy removal was not a bad economic move, but that government would have put some remedial measures that would have ameliorated the sufferings of the masses. International organizations, especially the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF), have hailed the fuel subsidy removal; they said that the removal will retool and kick-start economic transformation and growth. As plausible as their accolades might sound, fuel subsidy is the only welfare package Nigerian citizens are enjoying from their government. Even in the Western economies that allow the forces of demand and supply to hold sway, there are some measures of subsidy that give their citizens some respite and latitude to operate, especially in the area of agriculture. There is no economy that operates wholly an open or closed system; what obtains is mostly mixed economy. Policy Execution and Insensitivity As a primary function of the state, section 14(2) of the 1999 constitution as amended stipulates that the Nigerian government is to provide for the security and economic wellbeing of its citizens as one of the fulcrums of its legitimacy. Thus, security and economic wellbeing are interwoven and interrelated as one leads to the other. In recent times, security needs of the citizens embrace social, cultural, political and economic needs. This is because no nation that needs peace and development would pay lip-service to the basic needs of its citizenry as such neglect may lead to untold suffering and anarchy. Although the removal of fuel subsidy had foot-dragged over the years, by 2023 government was still unable to come up with sustainable palliative measures before the sudden removal. This sort of insensitive approach has characterized government policies in Nigeria since independence. And this has led to a high degree of developmental distortions that crystallize as poverty and suffering among the masses. Rather than weighing the pros and cons of government plans before announcing them, policymakers in Nigeria use suffering and hardship to test the pulse of citizens’ acceptance or rejection of public policies. The fuel subsidy removal is akin to the recent naira redesign in Nigeria where the CBN seemed not to know that the policy, especially the cash-limit aspect of it, would negatively affect the living standard of the people. Findings and Discussion As earlier mentioned, thirty (30) respondents from three geopolitical zones of Nigeria (namely, the South East, South South, and South West zones) were purposively interviewed. Respondents #1, #2, #6, #8, #9, #10, #25, #26, and #29 said that government’s action was not well thought out as it came when the economy was recovering from recession and the naira redesign crisis. Respondents #3, #4. #5, #11, #12, #13, #14, #15, #16, #19, and #24 revealed that no time was more propitious than the 29th May, 2023 Bola Ahmed Tinubu declaration that fuel subsidy was gone. They said the monumental corruption associated with the fuel subsidy regime was paralyzing the economy and enriching only a few individuals. Respondents #17, #18, #21, #22, #23, #24, #27, #26, #28, and #30 saw fuel subsidy as a cankerworm that had eaten into the nations treasure but observed that measures should have been put in place to cushion the sufferings of the common masses. Conclusion The oil sector is a very critical sector, as it is Nigeria’s main foreign-exchange earner as well as the sector that provides the petroleum products Nigeria uses domestically to power the vehicles engaged in the distribution of goods and services across the country. This study has observed and illustrated that an increase in fuel price would always have a multiplier effect that would shoot up the prices of goods and services in the country. It was also noted that to assuage the effect the increase in price of commodities might have on Nigerians, the price control Act (PCA) was enacted in 1977 as a way of controlling the forces of demand and supply. Although no government policy is expected to remain static, since the global economy is subject to change, a major change in government policy, such as fuel-subsidy removal in Nigeria, needs to be people-oriented; after all, the essence of governance is for the provision of socio-economic and security needs of citizens. Any government that is insensitive to the welfare of its citizens, especially in advanced democratic settings, is bound to lose re-election bid. But this is not often the case in many developing countries, especially Nigeria, where a politician could occupy an elective office as a result of rigging and manipulation of the electoral process. This is why such leaders come up with anti-people policies. A combination of appropriate timing and manner of implementation is what makes a policy seem good or bad. Deregulating the price of PMS, thereby allowing only market forces to determine its price, may be a defendable economic decision, but government should have embarked on basic remedial measures to cushion the effect of the removal on the masses. References Adubi, A.A. (2004). Agriculture: Its Performance, Problem and Prospects. In Imam-Bello & Obadan, M.I. (Ed). Democratic Governance and Development Management in Nigeria, Fourth Republic: 1999-2003. LGARDS, Ibadan. Akindele, R.A. (1988). Nigeria’s External Economic Relations, 1960-1985: An Analytical Overview. In Akindele, R.A. & Ate, B.E. (Ed) Nigeria’s Economic Relations with the Major Developed Market-Economy Countries, 1969-1985. NIIA In Co-operation with Nelson Publisher Limited Lagos. Atemie, J.A. (1996). Oil and Agriculture in Economic Development: The Nigerian Experience. In Alapiki, H.E. (Ed). Perspectives on Socio-Political and Economic Development in Nigeria. Volume. 1 Springfield Publisher, Imo State, pp-46-66 CEDCOMS (2003) Informal Security Groups in Nigeria in Historical Perspective. In Sesay , A. Ukeje, C. Aina, O & Odebiyi, A (Ed) Ethnic Militia and the Future of Democracy in Nigeria. Obafemi Awolowo University Press, Ile-Ife. Dele Sobowole, Tinubu Versus Buhari War Started Earlier than Expected. Vanguard Newspaper 6th August, 2023.Vanguardngre.com. https://www.cbn.gov.ng. Retrieved March 22, 2024. https://www.nigeriatradehub.gov.ng/Organizations/View-Details?OrganizationId=20 #:~:text=Between%201978%20and%201989%2C%20NNPC,in%20Port%20Harcou rt%20in%201965 https://www.sparkgist.com/record/ https://www.thecable.ng/opec-nigerias-oil-production-dropped-by-7-to-1-32m-bpd-in-february https://twitter.com/jrnaib2 Jhingan, M.L. (2009) International Economics (6th Ed) Vrinda Publication Limited Dehli Oaikhenan, H.E. (2004) Petroleum Resources: Development, Distribution and Marketing .In Imam-Bello & Obadan, M.I (Ed) Democratic Governance and Development Management in Nigeria’s fourth Republic,1999-2003. CLGARDS Ibadan Umoru, D.O. (2022). Devaluation of Naira, Shocks and Realities: Evidence Disciplining Strength. 4th Inaugural Lecture, Edo State University, Uzairue. 11th May, 2022. |

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||