International Journal of General Studies (IJGS), Vol. 3, No. 1, January-March 2023, https://klamidas.com/ijgs-v3n1-2023-01/ |

||

|

Accents in Linguistic Borrowing of English Personal Names in Izọn

By Stella Tonyo Akinola

Abstract With the influence of globalization, linguistic borrowing is inevitable. Language contact which is the bedrock of linguistic borrowing stands like a colossus. The phenomenon of borrowing personal names has had a long tradition in the Izọn culture. Many names of foreign origin have been present in the area for a long time. Some of these names have been adapted and nativized for a period of time. In recent borrowings, the foreign forms undergo some adaptation but show the tendency to resist complete adaptation, particularly in terms of spelling and pronunciation. Such pragmatically borrowed items carry significant sociolinguistic signal about the borrowers’ attitude. This paper seeks to investigate the extent of borrowed English personal names in Izọn and the accent with which they are pronounced. It also seeks to find out if the accent of the borrower reflects class or not. The research instrument adopted in this paper is interview. The study is rooted in Thomason & Kaufman’s integrated theory of language contact. The findings reveal that English names are enjoying a certain popularity, with increasing tendency amongst the Izons in UAT and that the influence of the Izon language seems to contribute to the observed accents. The study concludes that accents are endemic as evident from the data. Keywords: accent, linguistic borrowing, names, Izon, globalization Background to the Study Language as a social entity is closely linked with the social structure and the value system of a society. This gives rise to various ways of evaluating the different dialects and accents that emerge from such relationships. Every structure is a system in itself. The knowledge of the whole system is in the mind of the native speaker, and without such knowledge, sounds cannot be pronounced nor meaning understood. Cyrstal (2002) observed that children learn the melody of their language before they begin to speak. Within this period, there is room to develop and master local and foreign skills, in preparation for the day the vocal system gets developed enough to speak. Infants hear sounds that they come to recognize before words can be identified. Neural pathways are eventually established in the brain that link each sound with a meaning. When a word is frequently heard, its connection is solidified and the same goes for accent. Whichever accent the child hears from his environment, is what he holds unto. However, the first few encounters with words may likely determine the way they will pronounce them for the rest of their lives. This seems to be how accents are cultivated. During the second half of the nineteenth century, a number of societal shifts meant that contact with speakers of other languages became easier and more common. Factors such as increased travel opportunities, a growth in the middle class and a growth in universities and state sector education led to a move away from the sole preoccupation with classical languages (Lorch, 2016). Language contact which signifies culture contact, have been in the focus of interest, ever since some researchers became aware of the fact that, there is no language which would be freeof foreign elements and that languages influence one another at different levels. One of the commonest ways of creating words in human language is through borrowing. Borrowing in its simplest form means the process of taking words from one or more languages to fit into the vocabulary of another. It is important to mention that there is no language that is free from borrowing. Different forms of borrowing exist, ranging from loan-words, loan-blend to loan translation. Heath (1994) observed that languages may become mixed up with each other through the process of borrowing. Borrowing involves mixing the systems (languages). Everyday example abound; words for food, plants, music, institutions and so on, which the source language can even be identified. Problem Statement The global spread of English has had an impact on the naming practices. Name giving is related to a person’s sense of identity and the deliberate giving of a name that is taken from the English-speaking world implies a positive attitude towards the use of English and the values it is associated with. Giving of English names as first or middle names is a trend that is presently ravaging the Izon culture. The Izons seem to have embraced this considering the proliferation of names which are either English or look and sound like English. Since all languages have different accents and varieties of pronunciation, it is statutory that these names would have different pronunciation, pending on the level and manner of exposure to the English language. The accents with which these names are produced calls for attention. Aim and Objectives The aim of this study is to examine the accents that manifest in the pronunciation of some of the English personal names that the Izon people bear. Objectives

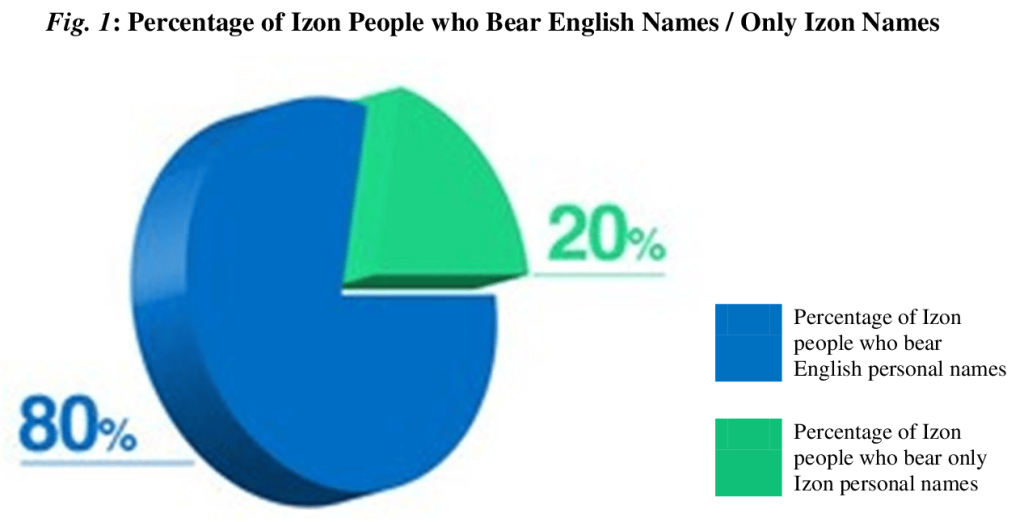

Scope The scope of this research covers the English names that originate from Anglo-American culture, including the names that go back to other languages, such as Hebrew, Greek or Latin and also pays attention to the accent with which they are pronounced. It covers two faculties: Social and Management Sciences and Basic and Applied Sciences. Significance The significance of this study lies in the fact that speakers of different varieties usually have different accents and speakers of the same variety may have different accents as well. The act of speaking and articulation of words or names has a link with self that other aspects of language do not seem to have. Thus, pronunciation has an intensely personal quality which can be revealed through such studies. Theoretical Framework Profile on Phonology (PROPH) and Prosody Profile were used in the analysis of the data gathered in course of the study. Profile on Phonology is an English profiling system that has three stages. The first is the profiling, the second is transcription and the third is matrixing. It is at the point of matrixing that the inconsistencies in sound production are revealed. Literature Review Some concepts that are relevant to the study were discussed. These include: contact language, borrowing, accent, naming, amongst others. Empirical review on some works that have been carried out in the area were also reviewed. Tone Ifode (1995) describes tone as variations in pitch that affect the meaning of words. Tone therefore, is a function of pitch in distinguishing meanings of words. Similarly, Ejele (1996) argues that tone is the significant, contrastive but relative pitch on each syllable. Thus, tone can be seen as the distinctive pitch level of a syllable that is found in the languages of the Sub-Saharan Africa amongst others. In tone languages, the tone carried by a word is an essential feature of the meaning of that word. So, tone performs a lexical function. Stress Stress is an important feature of speech which creates special problems to the Izọn speakers of English. As the airstream flow during speech, some effort is exerted for a sound but the effort exerted differs because some syllables are uttered with greater effort and muscular energy than others. Ifode (1995) defines stress as the degree of force employed in the production of a syllable. This implies that a syllable is stressed, if during its production, relatively greater articulatory energy is expended on it. Onuigbo (2010) explains that the syllables which are uttered with greater muscular energy are louder and longer and are therefore said to be stressed. Simply put, a change in stress means, a change in the degree of force with which the syllable is produced. Some syllables are said to be stressed while others are unstressed. Stress is meaningful in English just like tone. It is not surprising that a change in the stress pattern of a word may change the meaning and the word class completely. Contact Language Thomason (2001: 162) gives a broad definition of language contact induced change. “It is seen as any linguistic change that would have been less likely to occur outside a particular contact situation”. Aikhenvald (2006), on the other hand, observes that contact induced changes may be system altering or system preserving, pending on whether they involve restructuring of the grammatical system or borrowing of a term into an existing one. Kuteva (2017) stresses the importance of contact as she observes that two languages coming in contact may lead to transfer of linguistic materials from one contact language to the other. Such linguistic transfer constitutes contact induced change and encompasses a number of distinctive phenomena: syntactic and morpho-syntactic change in the two. Linguistic Borrowing Thomason and Kaufman (1988: 37) posit that linguistic borrowing is “is the incorporation of foreign features into a group’s native language by speakers of the language. In the literature, borrowing is also referred to as transfer or transference (Clyne, 2003). Trask (2000) and Aikhenvald (2006) share similar view in their description of borrowing. They describe borrowing as the transfer of features of any kind from one language as a result of contact. On the other hand, borrowing constitutes a completed contact-induced change, switching from one language to another constitutes a contact-induced speech behavior (Haspelmath, 2009). It is obvious that there is much more to the transfer of elements from one language to the other than mere adaptation at the levels of analysis. Many other factors play an extremely important part within the integration process of foreign elements into a receiving language. Wholly, the taking and integration of elements from one code to another is linguistic borrowing. Accent In sociolinguistics, an accent is a manner of pronunciation peculiar to particular individual, location or nation. All languages have different accents and other varieties of pronunciation. Accents refer “only to distinctive pronunciation” (Crystal, 2014: p24). Speakers of different dialects have different accents and speakers of the same dialect may also have different accents as well. Crystal added that the dialect known as “Standard English” is used throughout the world but it is spoken in a vast range of regional accents. Yule (2010) declares, “it is a myth that some speakers have accents while others do not.” Whether we speak a standard variety or not, we all speak with an accent, he added. Certain accents are perceived to carry more prestige in a society than others. This is often due to their association with the elite part of society but in linguistics, no difference is made among accents in regards to their prestige or correctness. However, an accent can be standardized or stigmatized. Naming In the field of linguistics, Onomastics is the study of proper names, especially the names of people (anthroponyms) and places (toponyms). Algeo (1992) observes that the study of personal names is closely related to geneology, sociology and anthropology. According to Hough (2016), Onomastics is both an old and young discipline. This is due to the fact that since Ancient Greece, names have been central to study of language, throwing more light on how humans communicate with one another and organize their world. The investigation of the origins of names is more recent in some areas while being still at the formative stage in others. McClure (2013) reports that nowadays more than six thousand (6000) personal names are registered as baby names in England and Wales, while there were probably fewer than one thousand (1000) names in use towards the end of the Middle Ages. Mencken (1962) observes that a large number and diversity of immigrants is mirrored in the diversity of names in the United States. Mencken added that the 19th century saw a growth in the use of middle names as given names. And that these tendencies have continued to increase, with the names haven become more and more imaginative and diverse. According to Herbert (1996), several names are possible throughout life and there were no surnames. Some studies indicate that in recent years English names have been growing in popularity. De Klerk (1999, 2002), found out that there is a trend towards English personal names among speakers of African languages. Out of one thousand (1000) official name changes, as documented in government gazettes in 1997, 34% of African language speakers either placed English name first or added an English name or replaced an African name with an English name. Three years later, the percentage of African name changes, preferring English, had risen to 38%. The main reasons according to De Klerk include: sociocultural, reflecting the wish to affiliate with a culture or linguistic group. This may be related to the highly favorable economic, social and educational status. Also, there are aesthetic reasons or reasons of personal taste, which may be connected to a desire for unique and different names. De Klerk concludes that taking on an English name is a symbol of upward mobility, upward education and multiculturalism. Similarly, Tan (2004) undertook a study on the influence of English naming conventions on Singaporean names. The study reveals that English naming conventions have greatly influenced the Singaporean naming system. Akinola (2020) also carried out a similar study on the personal name giving conventions and the names in Kolokuma. She observes that personal names in Kolokuma are not randomly assigned to people but given for specific reasons. Identity is the first thing but what follows is much more than identity as the names are meaningfully packaged. The colonial history left its mark on name-giving in Nigeria. With the establishment of a British government and a British educational system and through Christian missionary activities, Nigerians received English names in addition to their names and surnames were introduced. African naming traditions differ considerably from the English ones. African names are meaningful and they are unique. They typically relate to certain events associated with the birth of the child Methodology In conformity with the study objectives, a descriptive survey design was adopted. The target population in this study comprised two groups: lecturers and students in two faculties in the University of Africa: the Faculty of Social and Management Sciences and the Faculty of Basic and Applied Sciences. Fifty (50) students and fifteen (15) lecturers were selected. Simple random sampling was adopted in this study to ensure that everyone in the study population stands a chance of being represented. A table of random numbers was used with a random number generator to determine the sample size. The bulk of the relevant data for this study were collected through interview. The interviews were recorded to enable the researcher transcribe the correct responses from the respondents. Both qualitative and quantitative methods were employed in the presentation and analysis of the data. Data Presentation and Analysis The data collected in course of the study is presented here and interpretation of findings was made in accordance with the research questions that guided the study. To facilitate this, the bulk of the data is arranged orderly and presented in tables. The data were sourced from two categories of respondents, lecturers and students. The interview questions were designed for both categories of respondents. The total number of respondents interviewed were sixty-five (65) of which forty-one (41) were males and twenty-four were females. This gives a picture of male dominance in the two faculties. The number of respondents got streamlined by their responses to the interview questions. Out of the sixty-five (65) respondents, fifty-nine (59) of them are from Izon while six do not have Izon origin. Since the study is concerned about people of Izon origin who bear English names, the interview continued with the fifty-nine and the six were dropped. The fifty-nine (59) respondents were asked whether they have English personal name or names and forty-seven of them admitted having English personal names either as first or middle names. This means that 80% of the study population have English names while the rest do not bear any English name. The ratio is 4:1. The implication is that for every four, there is only one without an English name. Below is a pie chart showing the percentage of Izon people who bear English personal names and percentage of Izon people who bear only Izon personal names.

The next question addresses the issue of the giver of the name. We want to find out if the naming was done by any other person order than themselves or themselves. A good percentage (79%), which represents thirty-seven respondents, admitted that the English personal names they bear were given by persons other than themselves. These persons range from parents, guardians, aunts, uncles to siblings. The rest (ten respondents), which represents 21% of the study population, gave themselves the English names they bear. This is in consonance with Lee (2001) who said that some people gave themselves fancy names, expressing a desire for uniqueness. Based on this, one can speculate that increasing professional life, media and other forms of popular culture must have given rise to the proliferation of names which are either English or sound like English. Certain general development can be observed with the trend of English names present among the Izon people in UAT. The concept of modernization is the main thing. Others could be personal taste, which is based on existing cultural practices and beliefs that may shape the existing fashions and the future ones as well. Thus, the English names are integrated to existing names or they are used alone depending on the context. As it is evident, fashion and aesthetics have gained prominence. The English name phenomenon can be traced to the oil workers who worked in the environment. Their interaction with the oil workers, who in most cases were rich and had to spend money carelessly to the admiration of the people contributed greatly to the giving of English names. Some of the indigenes who loved their financial strength gave their names to their children. Persons with English names project them to the detriment of the native names while those without English names give themselves English names and also give prominence to them. There are cases where some names are only borne in some environments. Anyone who calls the right name in the wrong environment remains unidentified and the wrong name in the right environment also remains unidentified. This is a case of dual identity as a result of English names. Some persons whose English names were given by others order than themselves still had to change to cuter ones. The reason is not far-fetched. English and English person names enjoy the pride of place among the Izọn speakers, since it is associated with education, social and economic advancement. This contributes greatly to the hybridity of cultures and identities. The names given by the respondents in course of the study are stated below in a tabular form. The essence of the table is to display the correct transcription and stress pattern of the names given. The manner the English names were pronounced by the bearers of the names were recorded and transcribed as well. The stress patterns are also stated. Some of the respondents gave more than one name but only one was taken for the sake of analysis. This is to enable the researcher identify the accent with which such names were being pronounced. Table 1:

The data above is a revelation of the accents obtainable from the so-called English name bearers. It is crystal clear that the accents observable from the respondents are different from the English pronunciation. A lot of the sounds are pronounced differently and the stress pattern is also different. Taking a look at the first name in the data, “Beatrice”, the stress is on the first syllable [‘bi:tris] and the sound immediately the first consonant /b/ is a close, front vowel while the other has placed the stress on two different syllables. The first stress is on the first syllable while the second one is on the second syllable, [‘bia’tris]. Thus, one name has two stress marks and this makes the pronunciation quite different from the origin of the name. The sound that comes after the first consonant /b/ is a diphthong. The outright wrong use of stress and sound is bound to give a strange accent. The third item in the data is “Abigail”. A close examination of both transcriptions reveals the shortfall in stress and sound as well. The correct stress is placed on the first syllable [‘ꬱbәgeil] whereas the wrong one is placed on the third syllable, [a:bi:’gel]. The sound difference is also obvious. These are the things that account for a difference in accent. It is true that every language is spoken with an accent but this is a case where the native sometimes find it difficult to understand as a result of the strange accents in the pronunciation of personal names borne by the Izọn people. The entire data is anchored on the same premise as the example analyzed though with divers positions of stress placement and sounds, especially with the vowel sounds. A few consonant sounds are also interchanged, particularly the dental fricatives, /ɵ/ and /ð/. The following names, “Faith”, “Dorothy” and “Elizabeth” in 10, 14, and 21 in the data, have the voiceless dental fricative /ɵ/ in different environments but they were replaced with the voiceless alveolar plosive /t/ as shown: [‘feiɵ],[‘feit], [‘dↄrәɵi], [‘dↄra:’ti], [ә’lizәbәɵ], [‘eli’zabet]. In “Blossom”, the voiceless alveolar fricative is interchanged with the voiced counterpart, [‘blↄsәm][blo’zom]. The stress placements are also different. The serial number 9 in the data is also remarkable as “Joy” ,[‘ʤↄi] is pronounced [‘zoyi]. This is a case of interchanging the voiced alveolar fricative /z/ for the voiced palato-alveolar affricate /ʤ/. This trend appears to be more or less nativizing the borrowed English person names. The name bearers admire the names but lack the ability to pronounce them with the proper accent. This does not seem to be a problem because the environment accepts whatever accent the name bearer gives it. This occurs as a result of the difference in the sound systems of the two languages. Also, English language is a language that has stress while Izọn is a tonal language. Thus, its possible for the native speakers of English to hear an English name and not be able to identify the name as a result of the disparity in pronunciation. Summary of Findings The following findings were made. It is apparent that English names are enjoying a certain popularity, with increasing tendency amongst the Izons in UAT. About 80% of the respondents bear English names either as first or middle name. Almost 79% of the English names were given by parents while 21% gave themselves the names. This might not be unconnected with the fact that people tend to identify with the use of English and all the social characteristics associated with it. Influence or interaction with oil company workers who are rated very high because of their financial strength as pedals some to give English names to their children. Neurological constraints associated with brain development appear to be one of the causes of accents amongst them. The influence of the Izon language also seems to contribute to the observed accents. Conclusion Linguistic features are transferred from one language to another as a result of language contact, personal names inclusive. Quite a good number of UAT students bear English names which are either given by parents, guardians, siblings or self. It shows the place English occupies among the Izon people, where everyone is struggling to ensure that an English identity is attached to his/her identity. The accents with which these names are pronounced are nativized. Accents are processes sensitive to linguistic environment. Thus, this study concludes that accents within and beyond borders affect the pronunciation of English names amongst the Izọn speakers. Recommendations

Contribution to Scholarship This study has contributed to the body of existing knowledge. It has also contributed to the investigation of accents on English personal names by integrating perspectives from contact linguistics. References Akinola, S.T. (2020). An onomastic analysis of personal names in Kolokuma. In Adeniyi, H. Ibileye, G., & Abdul Malik (ed.). Issues in minority languages and language\development studies in Nigeria. LAN Algeo, J. (1992). Onomastics: The Oxford Companion to the English language, (ed.)., by McArthur, T. Oxford University Press. Aikhenvald, A.Y. (200). Grammars in Contact: A cross linguistic perspective. In grammars in contact, a cross linguistic typology (ed.). by Aikhenvald, A. Y. Oxford University Press Crystal, D. (2000). Language death. CUP. Crystal, D. (2014). The Cambridge encyclopedia of language. CUP. De Klerk, V. (1999). English personal names in international context. https://link.gale.com Ejele, P. (1996). An introductory course on language. Uniport Press. Haspelmath, M. (2009). Lexical borrowing: Concepts and issues in loan words in the world’s languages. A comparative handbook. In Haspelmath, M., & Uri’s (ed.). De Gruyter Mouton. p. 35 – 54. Hough, C. (2016). The Oxford handbook of names and naming. Oxford University Press. Ifode, S. (1995). Basic phonetics. Sunray Books Limited. Kuvela, T.(2017). Contact and borrowing. https/www.researchgate.net/publication. Lee, M. (2001). What’s in a name .com?: The effects of “.com” name changes on stock prices and trading. Strategic Management Journal, 22 (8) p. 793 – 804. Onuigbo, S. (2010). Oral English for schools and colleges. Africana FEP Publishers. Thomason, S.G. (2001). Language contact: An introduction. Georgetown University Press. Thomason, S.G. & Kaufman, T. (1988). Language contact, creolization and genetic linguistics. University of California Press. Trask, R.L. (2000). The dictionary of historical and comparative linguistics. Edinburgh University Press. Yule, G. (2010). The study of language (ed.). Cambridge University Press. *About the Author: Dr Stella Tonyo Akinola (stella.akinola@uat.edu.ng) is affiliated to University of Africa, Toru-Orua, Bayelsa State, Nigeria. |

||