|

International Journal of General Studies (IJGS), Vol. 2, No. 3, October-December 2022, https://klamidas.com/ijgs-v2n3-2022-06/ |

||

|

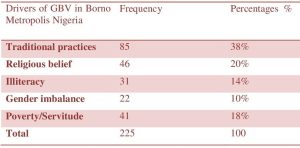

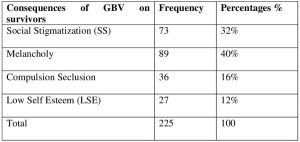

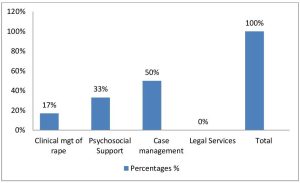

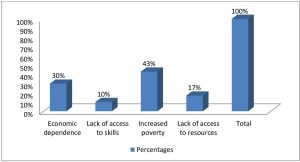

The Causes and Implications of Gender-based Violence on the Socio-Economic Status and Development of Women in Maiduguri Metropolis, Borno State, North-East Nigeria By Ikechukwu Stephen Okolie, Zara Kareto Mohammed, Ujuamara Ononye & Chukwuebuka Emmanuel Okolie* Abstract The research was conducted to identify drivers of gender-based violence (GBV) and its implications on the socio-economic status and advancement of women and the girl-child in Maiduguri Metropolis, Borno State, North-East Nigeria. The metropolis was ravaged by the actions of terrorist groups. The research objective is to measure the implications of GBV on the socio-economic status and advancement of women and the girl-child. The research adopted simple random sampling procedure and 225 participants took part in the research. Data were gathered through the use of an in-depth structured questionnaire named gender-based violence and socio-economic status and advancement questionnaire (GBVSEAQ). Results indicated the major drivers of GBV to be tradition (38%), religion (20%), illiteracy (14%), gender imbalance (10%) and poverty (18%). Regarding the consequences of gender-based violence on victims and survivors, the results are as follows: social stigmatization (32%), melancholy (40%), compulsory seclusion (16%) and low self esteem (LSE) or inferiority complex (12%). On the implications of GBV on the socio-economic status and advancement of women and the girl-child, the results point to servitude/poverty (43%), economic reliance (30%), lack of access to resources (17%) and lack of access to skills acquisition (10%). The results show that the available services to victims of GBV in the study area are clinical management of rape (17%), psycho-social support (33%), case management (50%) and legal aid service (0%). The research made some recommendations which include massive sensitisation of men on the effects of GBV on women and girls, setting up a legal aid corps to provide free legal services to GBV victims and prosecution of perpetrators of GBV. Keywords: GBV, SGBV, socio-economic development, Maiduguri, women, the girl-child

Introduction Globally, the menace of gender-based violence is on the increase and is affecting the physical and mental health of their female victims. Some of the victims have been killed by the perpetrators of the violence. The issue of sexual and gender-based violence is not peculiar to a particular region of the world but is a worldwide phenomenon. Uwameiye et al. (2013) defined gender-based violence as any form of cruelty or injurious act carried out against the will of a person or cruel act done against a person. This injurious act is said to be based on societal endorsement of disparity among the gender within the setting of a definite culture. Gender-based violence (GBV) is any form of dangerous action which can lead to psychological problems and sexual harm to girls and women. These psychological problems can emanate from bullying, intimidation and denial of independence and right (WHO, 2002). United Nations conference regarding abolition of all types of prejudice against young girls and women, defined GBV as any behaviour that is injurious to the emotional, bodily, sexual or mental wellbeing of the girl-child and women irrespective of age and race (Bott and Ellsberg, 2005). According to Sida (2007), sexual and gender-based violence is said to be any form of cruelty meted out against the girl-child, men and women which has a depressing effects on the sexual, emotional, psychological, self identification, advancement and total wellbeing of the individual. Research has traced the causes of violence to lack of equity, induced inequalities and gender prejudice in the society. In different societies around the globe, gender-based violence is becoming institutionalised. In other contexts, it is seen as an outcome of contrast in personality and ecological factors. In view of these facts, many intellectuals, scholars, organisations and research groups have decided to engage in massive community campaigns, advocacy and sensitisation about violent behaviour against girls/women and other types of gender-based violence (Okemgbo, Omideyi & Odimegwu 2002). United Nations pronouncement regarding the eradication of violent behaviour against girsl/women, defined aggression against young girls and women as gender-based violent behaviour which happens within the family and public settings that have psychological effects on women and girls. Furthermore, it is said to be an act of intimidation and coercion with the purpose of sustaining gender discrimination in the society (Beijing platform, 1995 and Odimegwu, 2000). Internationally, the cost implications of gender-based violence cannot be quantified; apart from the personal, family, communal and societal cost, gender-based violence also has massive financial and societal effects at all levels. Within the different societies of the world, the cost of close partner brutality most times is higher than the expenditure on basic education. The World Bank Group (2014) stated that in Peru the monetary cost for close partner violent behaviour is above 3.6 % of the Gross Domestic Product and less than 1.6% for basic education. United Nations attention regarding the global menace of sexual and gender-based violence gave researchers the opportunities and funding to carry out research on sexual and gender-based violence across the continents and the societies of the world. Results from the studies conducted in Africa indicated an increase in violent behaviour against the girl-child and women which are caused by different factors (Odimegwu & Okemgbo, 2003). In ECOWAS, Nigeria is on the forefront in carrying out scientific studies on the increasing menace of sexual and gender-based violence in the region and also finding solutions to the phenomenon. This gave researchers and scholars the opportunity to conduct research on GBV and documentation of prevalent violent behaviour against women and girls (Okemgbo et al., 2002). According to Jewkes et al. (2002), result from the nationwide assessment conducted in the rainbow state of South Africa statistically showed frequency of physical brutality to be at 26.5%. Another study conducted in Egypt showed incidence of bodily brutality at 35.5% (Centre for Health and Gender Equity 1999). Other locations of Sub-Saharan Africa surveys showed occurrence rates of 31% in Uganda, Nigeria 31.1%, Sudan 42.1% and Zambia 49% (Ahmed and Elmardi, 2005, Koenig, 2003, Kishor and Johnson, 2004). In Tanzania, result from national surveys on sexual violent behaviour showed frequency of forced sexual intercourse (rape) to be 4.2% and 6.6% in Nigeria (Fawole, et al. 2005 and McCloskey, Williams and Larsen, 2005). A national survey report has shown that 2 out of 5 girls and women had been raped in South Africa, and in the Eastern Cape town 7.4% were victims of sexual coercion and rape (Sidley, 1999). There are some factors which have been identified as the drivers of gender-based violence such as depression, anxiety, belligerent conduct, dissatisfaction, compulsion marriage and internal displacement occasioned by the onslaught of armed opposition group Boko Haram Terrorists (BHT) and the Islamic State of West African Province (ISWAP) in Borno State, North East of Nigeria. The activities of these terrorist groups operating in the region are continually fuelling prevalence of sexual and gender-based violence against girls and women in Borno State. The increasing number of Vesicovaginal fistula (VVF) cases in the state is linked to underage marriage of the girl child and sexual violent behaviour against women in Maiduguri, Borno State Nigeria. According to Okolie et al (2021), there is a correlation between underage wedding, conjugal violent behaviour, sexual and gender-based violence and VVF, especially in Northern States of Nigeria. Statement of the Problem Gender-based and sexual violence is becoming a concern in Nigeria because of its increasing prevalence and implications on the overall safety of women and girls in our society. Within the South West region of Nigeria, a study conducted on sexual and gender-based violence showed that 62.1% of married ladies are battling intimate partner brutality, verbal abuses and aggression, psychological abuses and intimidation (Fatusi and Alatise, 2006). In Namibia, a country survey indicated that 60.1% of battered women had suffered trauma, emotional abuses and coercion from their partners and these have increased the level of fear and depression in them (Nangolo, 2003). According to Ndungu (2004), gender-based violence has permeated all strata of the society whereby spouses intimidate or coerce their partner to be submissive, loyal and obedient which is against the will of the victims. According to Himanshu and Panda (2007), a global survey stated that 1 in every 5 women worldwide are faced with certain types of domestic violence, sexual and gender-based violence in the course of their existence, and in most cases victims sustain severe injuries and pass away. According to United Nations Population Fund (2018), the incidence of sexual and gender-based violence is becoming alarming in Nigeria, especially in the North East region ravaged by the insurgent groups, Boko Haram terrorists and the Islamic State of West African Province (ISWAP) and in the North West region currently experiencing the unleashing of terror by herdsmen and bandits. In Nigeria, about 4 in 10 women suffered domestic or gender-based violence before they clocked 15 years of age. A 2013 National Demographic Health Survey indicated that about 28.1% of women and young girls were victims of domestic and gender-based violence which spread across cultural and socio-economic boundaries (Okwundu, 2017). Sexual and gender-based violence and other forms of violence against women and the girl-child are increasingly becoming a concern, especially in the camps sheltering Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) in Maiduguri, Nigeria. Most cases of violence were carried out by safety personnel saddled with the responsibilities of protecting occupants of these camps. Members of the insurgent groups and security forces are said to be the perpetrators of sexual violence and other violent behaviour against young girls and women in the IDP camps in this paper’s area of research (Okolie et al. 2021). In Borno State, factors like culture, customary norms, and religion are said to have hindered public acknowledgment of domestic violent behaviour, sexual and gender-based abuses. The communal imposition of the male child over the girl-child has led to the weakening of women, thereby making them to be at the receiving end of violent behaviour and subjecting them to economic hardship and perpetual reliance on their spouses (Okolie et al., 2021). A survey conducted in North-Western and North-Eastern regions of Nigeria in 2020 indicated 73.1% rate of sexual and gender-based violence against women and young girls in the regions. Another regional survey also showed that 48.1% were married before the attainment of 15 years of age, and this adversely affects the health, fertility and general wellbeing of the girls. Sexual and gender-based violence impede the advancement and socio-economic development of women as it limits them from pursuing and realising their goals in life. It is as a result of these that this research was conducted to examine drivers and implications of sexual and gender-based violence on the socio-economic advancement, wellbeing and growth of women and young girls in Maiduguri Metropolis of Borno State, North East Nigeria. Specific Aims of the Research The aims of this study are stated as follows:

Research Questions The following questions were adopted for this study:

Methodology The study adopted descriptive survey method and respondents were sampled from the 15 political wards in Maiduguri Metropolitan Area Council (Bolori I, Bolori II, Bulablin, Fezzan, Gamboru, Gwange I, Gwange II, Gwange III, Hausari, Lamisula, Limanti, Mafoni, Shehuri North and Shehuri South) of Maiduguri Metropolitan Area Council (MMC) of Borno State, North East Nigeria. Two hundred and twenty five (225) respondents, comprising fifteen (15) respondents from each of the political ward in MMC, were randomly picked. An in-depth structured questionnaire was developed and administered to each of the respondents by the field data assistants who are proficient in English, Hausa, Marghir, Bura and Kanuri dialects spoken in Borno State, North East Nigeria. The study utilized table summary and charts to present data collected from the research in line with research questions and aims of the study. Categories of Sexual and Gender-based Violence Research has shown we have different categories of gender-based violence which are explained below: Female Genital Mutilation (FGM): This type of cruelty and violence against young girls and women is prevalent in the North East, countries of Sub-Saharan Africa and North Africa and in some countries in the Americas, Asia and Europe. The female genital mutilation or circumcision is carried out by traditional practitioners who are not medical professionals or trained health workers. There is high risk of bleeding, infection and possibly death. Globally, there are about twenty nine countries where female genital mutilation (FGM) is still carried out. Majority of the girls before they clock 5 years undergo female genital mutilation; other girls go through it from 5 years to 14 years. Female genital mutilation or female genital cutting is classified into four types: removal of the clitoral hood, removal of the labia minora, removal of the labia majora and cauterization of the clitoris. According to Sida (2007), the number of young girls and women who have undergone female genital mutilation stood at 90.1% in Egypt, Guinea, Somalia and Djibouti. In countries like Nigeria, Republic of Niger, Uganda, Ghana, Togo and Cameroon, the rate is 5.1%. During the process of carrying out the female genital mutilation, victims suffer blood loss and infection. Sexual Violent Behavior: This is sexual cruelty against a person which is usually done by a single individual or group of persons. Majorly, sexual brutality occurs in the public, in private homes and in other environments. Those who carry out the sexual brutality are known by the victims who are members of the society where the victims belong. Sexual cruelty can come in any form like sexual stalking, gang sexual assault, spouse sexual assault and enforced pregnancy termination (Ganley, 1998). Bodily Cruelty: Bodily violence can come in different forms which are not limited to hitting, beating, twisting, slapping, boxing, and use of objects on the victims. The bodily cruelties are carried out by the perpetrators to instill fear in the body and mind of the victims. Most times the bodily assaults might or might not cause internal or external injuries on the victims (Okwundu, 2017). Emotional and Mental Cruelty: The psychological violence is risk to life, depression, distress, personality seclusion and lack of affection and emotional disconnection which often result to individuals committing suicide. Theoretical framework The research was anchored on the social learning theory which is also called intergenerational theory. The social learning theory talks about family unit cruelty which is said to be a “learned phenomena” stating that there is an intergenerational correlation between violent behaviour and a person’s learned attitudinal functions. This intergenerational and behavioural attitude is developed from infancy and established in the course of grooming a child (Johnson, 1988). Gelles (1972) stated that families do not only expose persons to violent behaviour; methods of aggression the family unit permits encourages the use of violence as a means to control and establish supremacy by the male folks over the females. Finkelhor, Hotaling and Yllo (1988) stated that individuals who are victims of abuse and coercion are prone to suffer from social stigma, helplessness and lack of trust on others. The individuals also suffer from trust issue and inability to make input that will lead to the growth of their locality which hampers the advancement of regular surviving procedure, thereby leading to cruelty. The postulation about cruelty is that such violent behaviour is a learned reaction which is passed on and toughened across family generations (Carden, 1994). Walker (1989) advanced a “cycle theory of violence” that highlights distinctive stages of cruelty suffered by girls in a digressive family-unit violent behaviour, which are increasing anxiety, sudden increase of cruelty and a nuptial phase. The main thrust of the social learning/intergenerational theories is based on the foundation of family-unit interpersonal relations and dynamics. Walker (1984) has made contributions to the understanding and thought about family-unit violence and family generational violence. Presentation of findings Table 1. Drivers of Sexual and Gender-based Violence in Maiduguri Metropolis Borno State North East Nigeria Table 1 below highlighted drivers of sexual and gender-based violence in Maiduguri Borno State North East Nigeria analysed in frequency and percentages. Table 1. Drivers of Sexual and Gender-based Violence in Maiduguri Metropolis

Table 1 above indicated the major principal drivers of gender-based violence in Maiduguri Metropolis, Borno State Nigeria, which showed that traditional practices constitute 38%, religious beliefs 20%, illiteracy 14%, gender imbalance 10% and poverty and servitude 18%. The data gotten and analysed indicated that traditional practices are the main principal drivers of gender-based violence in Maiduguri Metropolis, Borno State, Nigeria. Table 2. Consequences of SGBV on Victims in Maiduguri Metropolis There are consequences of sexual and gender-based violence on the victims who happened to be vulnerable young girls and women in our societies. Many of the victims of sexual and gender-based violence end up committing suicide because of the factors identified below in table 2. Table 2 below showed the consequences of sexual and gender-based violence on victims in the location of the study. Table 2. Consequences of SGBV on Victims in Maiduguri Metropolis

Table 2 summarised the consequences of sexual and gender-based violence on victims in Borno State Metropolis North East Nigeria. Data analysed indicated the followings: social stigmatization 32%, melancholy 40%, compulsion seclusion 36% and inferiority complex or low self esteem (LSE) 12%. The victims of sexual and gender-based violence in the study area are going through so many challenges which have affected their mental health and wellbeing. Figure I. Available Service to Victims of SGBV in Borno State Metropolis Nigeria There are services which are meant to be available for survivors of sexual and gender-based violence in Borno State Metropolis, North East Nigeria, which will help in the management of sexual and gender-based violence cases in the state. Data gotten and analysed have shown the availability of the following services for victims of SGBV in the study area.

The figure I above has shown the rate of available services which are accessible for the victims of sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) in Maiduguri, Borno State, North East Nigeria. The bar chart indicated that case management is 50%, psycho social support 33%, clinical management of rape 17% and legal aid services 0%. The presence of Non Governmental Organisations providing humanitarian services to the displaced population in Borno State, North East Nigeria due to the insurgency enhanced access to clinical management of rape cases and psycho-social support services available to victims of SGBV in the area of study. According to findings, there are no legal aid services for victims of SGBV in Borno State North East Nigeria. The lack of legal service to victims of SGBV can be attributed to religious and traditional belief systems. There are no legal aid council advocating for the fundamental rights of sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) victims. Likewise, there was no prosecution offenders in the study area. Figure II Implications of Sexual and Gender-based Violence on Socio-economic Status and Advancement of Girls and Women in Maiduguri Metropolis Globally, the implications of sexual and gender-based violence on the socio-economic status and advancement of girls and women cannot be accurately measured. But researches have shown that the implications of SGBV on girls and women are hindering their rapid socio-economic development, growth and economic freedom.

Socio-economic status and development of women are grossly affected by the prevalence of sexual and gender-based violence, especially in third world countries of the world where women are seen as only good for child bearing. In North and Sub Sahara African countries, women are marginalised and subjected to all kinds of sexual abuses and domestic violence. The aggressive and violent nature of some men against their wives has negative implications on the wellbeing, social, economic advancement and mental health of women and young girls. The implications of SGBV on the status and socio-economic advancement and growth of young girls and women in the area of study are many but our research indicated the following results: economic reliance 30%, prevalence of poverty 43%, lack of access to resources 17% and lack of access to skills 10%. Sexual and Gender-based violence is becoming a menace in Maiduguri Metropolis and it is caused caused by many factors. The traditional system, religious inclination, fear of speaking out and social stigma are some of the triggering factors for the increasing rate of SGBV in the study area. The non existence of legal action and prosecution of GBV perpetrators has made the offenders to continually carry out the act knowing that nothing will happen to them because their tradition and religious system protects them and prohibits victims against speaking out or taking legal action. Conclusion Violence against young girls and women is a common phenomenon in our society today and this should be a matter of concern to all agencies and governments at all levels. There are drivers which are triggering the prevalence of GBV and its implications on the victims. The drivers of GBV in the area of study are noted as follows: traditional practices, religious inclination, illiteracy, gender imbalance and abject poverty. The most vulnerable victims of GBV are women and girls and these victims suffer social stigmatization, melancholy, coerced seclusion and inferiority complex. Self isolation from the public and depression most often prompt victims of GBV to become very aggressive; some commit suicide out of frustration. The socio-economic status, advancement and growth of girls and women are stalled by various gender-based violence problems that strangulate and quench the drive for economic independence and advancement of women. The strangulation of economic drive or self-reliance of the girl-child and women has led to high rate of poverty among girls and women, most of whom lack financial and economic resources for self-reliance. It is pertinent that women’s access to acquire and own assets, and their access to credit facilities and gainful employment with appropriate wages for work carried out must be assured. Their inheritance rights also should be protected. Women and girl-child education must be a top priority of development partners and different levels of government. This will help in bridging the educational gap that exist between men and women and also help in making girls and women aware of their fundamental human rights and other rights enshrined in local and international laws. The societal, religious and cultural understanding that men are superior to women needs to be addressed to curtail abusive mentality of some men in our society. The notion of equity must be advanced in our society to promote economic development and self reliance of women, as this will decrease the rate of violence against women in our society. Recommendations At end of the research the following recommendations were made:

References Ahmed, A. M., and Elmardi, A. E. (2005). A Study of Domestic Violence among Women attending a Medical Centre in Sudan. East Mediterranean Health Journal, 11, 164–174. Beijing Platform (1995). Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action: Fourth World Conference on Women, Beijing, China, 4-15 September, 1995. Bott, S. and Ellsberg M. (2005). Preventing and responding to gender-based violence in middle and low-income countries: a global review and analysis [Online] Available at http://www.researchgate.net/publication/23723131 Accessed on: 15 June 2022. Carden, A. D. (1994). Wife abuse and the wife abuser: Review and recommendations. The Counseling Psychologist, 22(4), 539–582. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000094224001 Centre for Health and Gender Equity (1999). Population reports: Ending Violence Against Women. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health and Centre for Health and Gender Equity. Accessed at http:/www.infoforhealth.org/pr/l11/violence.pdf on 20 June 2022. Fatusi, A. O. and Alatise, O. I. (2006). Intimate Partner Violence in Ile–Ife, Nigeria: Women’s Experiences and Men’s Perspectives. Gender and Behaviour, 4, 764–781. Fawole, O. I., Ajuwon, A. J. and Osungbade, K. O. (2005). Evaluation of Interventions to Prevent Gender-Based Violence among Young Female Apprentices in Ibadan, Nigeria. Health Education, 105, 2–9. Finkelhor, D., Hotaling, G.T and Yllo, K. (1988). Stopping Family Violence, Research Priorities for Coming Decades. Ganley, A. (1998). Improving the Health Care Response to Domestic Violence: A trainers Manual for Health Care Providers. Family Violence Prevention Fund. Gelles, R. J. (1972). The violent home: A study of physical aggression between husbands and wives. Sage. Himanshu, S.R and Panda, P.K. (2007). Gender and Development: Dimension and Strategies Introduction and Overview, MPRA Paper 6559, University Library of Munich, Germany. Jewkes R, Watts C, Abrahams A, Penn-Kekana L and Garcia-Moreno C. (2002). Conducting Ethical Research on Sensitive Topics: Lessons from Gender-Based Violence Research in Southern Africa. R Health Matters 2000; 8: 93–103. Johnson, H,. (1998) Social control and the cessation of assaults on wives. PhD thesis University of Manchester, Manchester United Kingdom. Kishor, S. and Johnson, K. (2004). Profiling violence: A multi-country study. Measures DHS, ORC Marco, 53-63. Koenig, M.A., Lutalo, T., Zhao, F., Nalugoda, F., Wabwire-Mangen, F., Kiwanuka, N., Wagman, J., Serwadda, D., Wawer, M and Gray, R. (2003). “Domestic Violence in Rural Uganda: Evidence from a Community-Based Survey.” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 81:53–60. McCloskey, L. A., Williams, C. and Larsen, U. (2005). Gender Inequality and Intimate Partner Violence Among Women in Moshi: Tanzania. International Family Planning Perspectives, 31, 124–140. Nangolo, H. N. (2003). Violence Against Women and Its Mental Health Consequences in Namibia. Gender and Behaviour, 1, 16–33. Ndungu, N. (2004). Gender-based Violence within Africa Region. An Overview of United Nation Wilaf News. Odimegwu, C.O. (2000). “VAW Prevention Initiatives: Changing Societal attitudes to violence against women”, Research Report submitted to J.D. and C.T. MacArthur Foundation Fund for Leadership Development Program, Nigeria. Odimegwu, C.O. and Okemgbo, C.N. (2003). Gender role ideologies and prevalence of domestic violence in South East Nigeria”, The Anthropologist ,(forthcoming). Okemgbo, C. N., Omideyi, A. K., and Odimegwu, C. O. (2002). Prevalence, patterns and correlates of domestic violence in selected Igbo communities of Imo State, Nigeria. African journal of reproductive health, 101-114. Okolie, I.S, Mohammed, Z.K and Ononye, U. (2021). Domestic Violence Against Women In Maiduguri Borno State Nigeria. Journal of Humanities and Social Policy Vol 7 Issue 1, E-ISSN 2545-5729 P-ISSN 2695 2416. Okwundu, S.C (2017). Gender-based Violence in Nigeria: A Review of Attitude and Perceptions, Health Impact and Policy Implementation. Texila International Journal of Public Health Volume 5, Issue 4. Swedish International Development Corporation Agency (Sida) (2007). Action Plan for Sida’s Work against Gender-Based Violence 2008-2010. Sida Gender Secretariat. http://www.sida.se/contentassets/ Accessed 24 June 2022. Sidley, P. (1999). Doctors demand AIDS drugs for women who have been raped. British Medical Journal, 318, 1507. World Health Organization. (2002). World Report on Violence and Health. Geneva, Switzerland.https://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/world_report/en/full_en.pdf?ua=1. Retrieved 21 June 2022. United Nations Population Fund (2018). Humanitarian Action 2018 Overview. <http://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pubpdf/UNFPA_HumanitAction_2018_Jan_31_ONLINE. pdf>. Retrieved on 21 June 2022. Uwameiye B.E and Iserameiya F.E (2013). Gender-based Violence Against Women and Its Implication on the Girl Child Education in Nigeria. International Journal of Academic Research in Progressive Education and Development Vol. 2, No. 1 World Bank Group (2014). Voice and Agency: Empowering women and girls for shared prosperity. Walker, L. A. (1984). Battered women, psychology, and public policy. American Psychologist, 39(10), 1178–1182. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.39.10.1178 Walker, L. (1989). The Battered Woman Syndrome. New York, NY: Harper and Row. *About the Authors: Ikechukwu Stephen Okolie (Ikechukwu.okolie@unimaid.edu.ng) and Zara Kareto Mohammed are of the Centre for Peace, Diplomatic and Development Studies, University of Maiduguri, Borno State, Nigeria while Ujuamara Ononye and Chukwuebuka Emmanuel Okolie are of Department of Psychology University of Nigeria, Nsukka, and Federal School of Social Work, Emene, Enugu, respectively. |

||