International Journal of General Studies (IJGS), Vol. 2, No. 3, October-December 2022, https://klamidas.com/ijgs-v2n3-2022-01/ |

||

|

Gender Dimension of Conflict among Non-Academic Staff of Selected Public Tertiary Institutions in Southeast Nigeria By Chukwujekwu Charles Onwuka, Emmanuel Echezona Nwokolo, & Sunday Chike Achebe* Abstract Conflict is a necessary and inevitable phenomenon in every social group. However, conflicts when ill-managed can generate unwanted atmosphere that could constrain organisational cooperation and the realisation of the ultimate goals of an organisation. Despite the fact that work-related conflicts constitute a recurring theme within organisational literature, empirical researches in relation to the gender-dimensions to work-related conflicts are scare, particularly within the context of non-academic employees in the Nigerian public tertiary institutions. This study therefore investigated gender dimension of conflict among non-academic staff in selected public tertiary institutions within the South-East zone of Nigeria. The study adopted the descriptive cross-sectional survey research design. The sample size for the study was 374 employees comprising of 143 males and 231 females, who were selected for the study through the proportionate stratified random sampling technique. Data for the study were collected through questionnaire administration and data collected were processed using the SPSS software package version 26. Data analysis was performed using descriptive statistics and the chi-square test was conducted to examine the relationship between gender and forms of conflicts among the employees. Findings of the study showed that there was actually a variation in the gender-dimensions of work-related conflicts, where the male employees were most inclined to ‘process conflicts’, while the female employees were most inclined to ‘relationship conflicts’. Result of the chi-square test suggested that there was a statistically significant relationship between gender and forms of conflict among the non-academic employees in public tertiary institutions (p = .000). Further results showed that the major effects of work-related conflicts equally varied significantly between the genders, where the major effects for the males included lack of trust, lack of cooperation with co-workers, antagonism and job discontentment, while the effect for the females included lack of cooperation with co-workers, hostility, antagonism, mutual suspicion, and low commitment. The study concluded that understanding gender-dimensions to work-related conflicts among the non-academic employees was a panacea to addressing issues affecting employees’ workability and organisational productivity. The study therefore recommended the need for conflict management committees in public tertiary institutions to consider designing programmes targeted at addressing the gender-specific conflicts among employees. Keywords: employees, gender, conflict, tertiary institution, dimension Introduction From the sociological perspective, conflict is a necessary and inevitable phenomenon in every social group, as it sets boundaries for acceptable and unacceptable behaviours within groups. However, conflicts can equally generate unwanted atmosphere for organisational integration, as heightened and ill-managed conflicts can mar organisational efficiency, cooperation among individuals, and constrain the ultimate goals of an organisation. According to Coser (1967) as cited in Omisore and Abiodun (2014), conflict is a struggle over values and claims to scarce status, power and resources in which the aims of the opponents are to neutralize, injure or eliminate the rivals. It could occur within a group especially when there seems to be incompatible values or unresolved differences among individuals within the inter-group or intra-group context (Ugwuanyi & Idoko, 2012). Despite the fact that organisational conflicts have been a recurring topic within organisational literature, one interesting aspect that seems to have been overlooked by researchers is the gender dimension of conflicts within organisations. This loophole in empirical literature may create a policy gap in relation to strategies to minimize organisational conflicts because when the gender dimension is not considered in designing conflict resolution strategies, it may create a one size fits all approach for conflict resolution, which may not help to adequately address the challenges. Approaching organisational conflicts from the gender dimension is important considering the fact that gender behavioural dispositions in work places have linked with role congruity (Gentry, Booysen, Hannum & Weber, 2010). This implies that conflict behaviorial dispositions would likely vary between males and females in the work place. Thus, it makes sense to argue that when the gender dimensions of organisational conflicts are determined, the resolution mechanisms may be easier to apply compared to when a generalist approach is applied. Conflicts are inevitable in public organisations like the public tertiary institutions and this could be more pronounced among the non-academic employees within various tertiary institutions in Nigeria considering the view that the non-academic staffs of public tertiary institutions in Nigeria are unique in their characteristics, with their peculiar work related issues that generate heightened conflicts among them. Although a number of studies have been conducted on work-related conflicts within the tertiary institutions in Nigeria (Abolo & Oguntoye, Ihuarulam, 2015; Ndum & Okey, 2013; Umo, 2014), none of these studies have been able to inquire on the gender dimensions of conflicts among non-academic employees of tertiary institutions, particularly within the context of public tertiary institutions in south-eastern Nigeria. This is a huge knowledge gap within the extant organisational literature which this present study intends to fill. Filling this knowledge gap is important considering the view that it would help to identify the gender-specific conflicts that often interfere with smooth operations of employees’ workability and productivity, which is very essential for the growth of the organisation. Objectives of the Study

LITERATURE REVIEW Concept and Dimensions of Conflict Conflict has been a recurring concept within the ambit of extant academic literature, perhaps due to the peculiar nature of the concept as a common phenomenon in human existence. Consequently, various scholars have conceptualised it differently based on their understanding and the socio-cultural, economic, political or religious context of their analysis. For instance, Thomas (1992) defined conflict as ‘the process which begins when one party perceives that another has frustrated, or is about to frustrate, some concerns of his’ (p. 1). Scholars like Berger and Luckman (1966, as cited in Dennen, 2005), also defined conflict as incompatibility of interests, goals, values, needs, expectations, and/or social cosmologies (or ideologies). Ideological conflicts especially have a tendency to become malicious. Borrowing a leaf from these conceptualisations, it could be summarised that conflict results due to conflict of interest among the conflicting parties. In terms of the dimensions of conflict, certain conceptualisations have been most popular within the organisational conflict literature. For instance, conflict has been conceptualised from the cognitive dimension of conflict (Amason, 1996), also referred as task conflict (Simons & Peterson, 2000), which arises from differences in judgment or perspectives among team members; issue conflict or substantive conflict (Guetzkow & Gyr, 1954;), which refers to the perception of disagreements among team members regarding the content of their decisions and involves differences in viewpoints, ideas, and opinions (Simons & Peterson, 2000). The affective dimension of conflict (Amason, 1996), also labelled as relationship conflict (Simons & Peterson, 2000), emotional conflict or interpersonal conflict – a perception of interpersonal clashes and typically includes anger, frustration, tension, annoyance, and animosity among team members (Simons & Peterson, 2000). One of the interesting classifications is that which provides three distinct classifications of work related conflict viz: relationship conflict, task conflict and process conflict (Omisore & Abiodun, 2014). Relationship Conflict: This exists when there are interpersonal incompatibilities among group members, including personality clashes, tension, animosity and annoyance (Jehn, 1995). This type of conflict produces negative individual emotions, such as anxiety, mistrust, or resentment, frustration, tension and fear of being rejected by other team members (Jehn, 1995). Task Conflict: According to DeDreu et al. (2003), this form of conflict could arise when there is disagreement on decision about procedure, allocation of funds, implementation of policies, and the contents of assignments. For scholars like Anwar, Maitlo, Soomro and Shaikh (2012), task conflict means the disagreement, difference of opinion and contrasting argument of staff while working in organizations. It represents a workplace disagreement over the best way to accomplish work tasks. For example, employees within a unit may disagree about the pattern in which tasks are distributed for each member of the organisation (task conflict relating to division of labour). In other scenarios, task conflict may arise due to the manner in which the resources are distributed across the employees (task conflict relating to allocation of resources); and another instance could be conflicts relating to task expectations. For example, when there is task ambiguity, a subordinate may perform a task incorrectly, which could trigger conflict between the superiors and the subordinate. Process Conflicts: This refers to disagreement about how a task should be accomplished, individuals’ responsibilities and delegation (Jehn & Mannix, 2001), e.g. when group members disagree about whose responsibility it is to complete a specific duty. Process conflict has been associated with lower morale, decreased productivity and poor team performance (Jehn, 1997). Process conflict could simply mean the disagreement over the procedures or methods the team or group should use for completing its tasks. It happens when procedures, policies, and strategies clash. METHODS This study was conducted within selected public tertiary institutions in south-eastern Nigeria. The South-East is one of the six geo-political zones in Nigeria; it has five states: Abia, Anambra, Ebonyi, Enugu and Imo. This study adopted the descriptive cross-sectional survey research design, which is a research design that helps to provide data that can be used to describe the peculiar characteristic of a target population or to describe the relationship between variables of interest in a study, within a specific point in time (Ihudiebube-Splendor & Chikeme, 2020). The choice of this research design was based on the consideration of its flexibility and cost-effectiveness in generating robust and reliable data within a short time frame. The design equally allowed the researcher an opportunity to use a sub-set of the population to describe the characteristics of a larger population in order to generalize the findings to the entire population. The target population comprised of all the non-academic employees within the selected public tertiary institutions. The proportionate stratified random sampling technique was adopted in the selection of 374 respondents who were administered with a questionnaire. Data for the study were collected by the researchers with the help of two other research assistants who were duly briefed on the purpose of the study. Data collected were coded into the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software version 26, which aided in processing all the relevant statistical data. Thereafter, the processed data were subjected to descriptive analysis using frequency count and percentage as well as inferential statistics involving test of study hypothesis using the chi-square statistic. RESULTS Table 1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Respondents

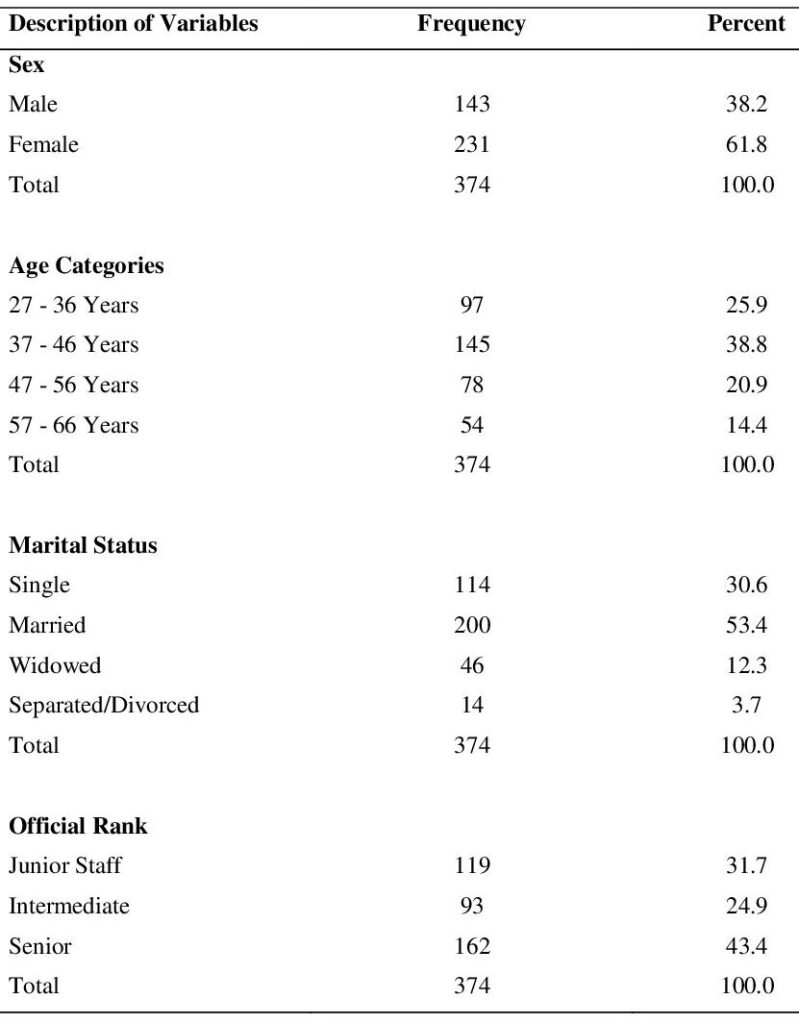

Table 1 contains information on the analysis conducted in relation to the socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents. The data showed that majority (61.8%) of the study participants were female non-academic employees participated in the study compared to slightly lower proportions (38.2%) of males. The age distribution of the respondents showed that the largest proportion (36.5%) of them aged between 37 – 46 years old, while the least proportion (14.4%) were those who aged between 57 – 66 years old. For marital status, data analysis showed that slightly more than half proportion (53.4%) of the respondents were married, compared to about a quarter proportions (30.6%) of them that were yet unmarried/single. Data analysis equally showed that the highest proportions (43.4%) of the respondents within the sample were senior level employees within the selected public tertiary institutions. This was followed by about a quarter proportion (31.7%) of junior employees, as well as 24.9% of them who fell within the intermediate level. This implies that the respondents were experienced enough within their organisations to respond to issues regarding gender dimensions of conflicts within their various organisational units. Sources of Conflict among Non-Academic Employees of Public Tertiary Institutions

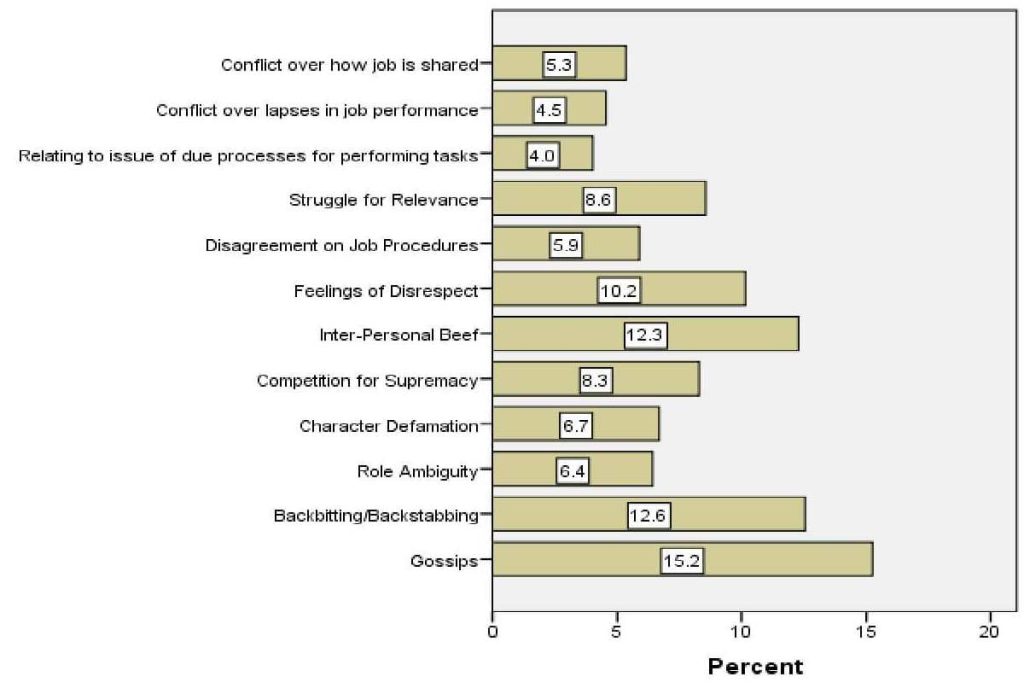

In the bid to determine the gender dimensions of conflict among employees within the study area, we first analysed the overview of respondents’ views on the forms of conflict among the employees (both males and females). As shown in figure 1, majority form of conflict, as indicated by the highest proportion (15.2%) of the respondents, is that of gossip. This was equally followed by backbiting/backstabbing as indicated by 12.6% of the respondents. Other options that garnered significant response by 12.3% of the respondents are that of inter-personal beef, followed by feelings of disrespect as indicated by 10.2% of the respondents. Thereafter, these data were sorted in according to the three forms of conflict used as the framework of analysis in this study (relationship, task and process conflicts). This system facilitated the analysis of gender dimension of conflicts as presented in figure 2.

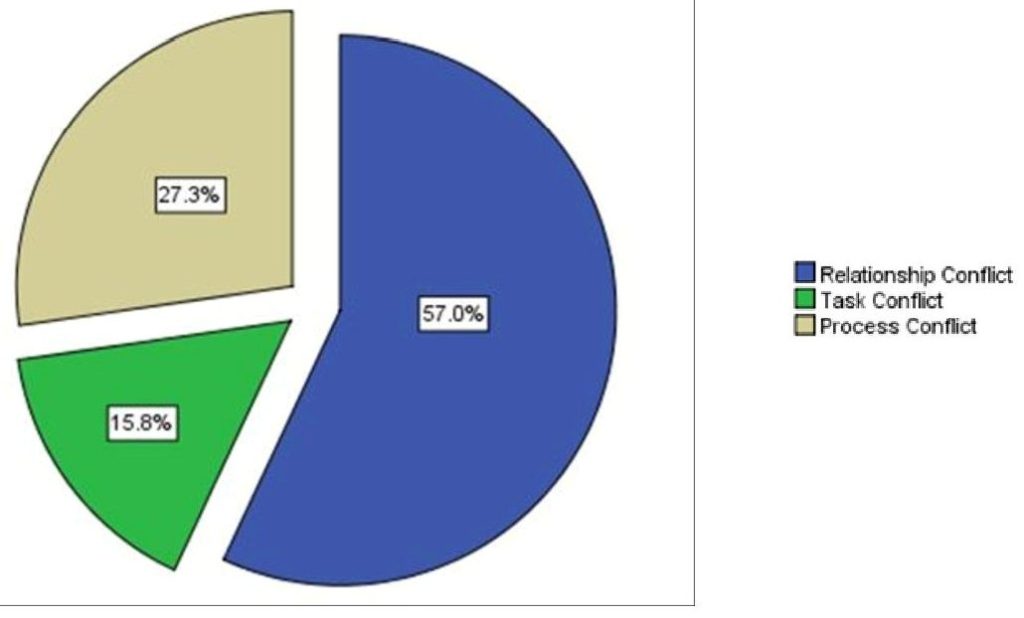

Data contained in figure 2 showed that majority of conflicts among non-academic employees of public tertiary institutions within the Southeast Nigeria, as indicated by more than half proportion (57.0%) of the respondents was relationship related. This was followed by conflicts related to process of job performance as indicated by about a quarter proportions (27.3%) of the respondents, while the least was conflicts associated with tasks, as indicated by 15.8% of the respondents. Further analysis showed the gender dimension of conflicts among the employees as presented in figure 3.

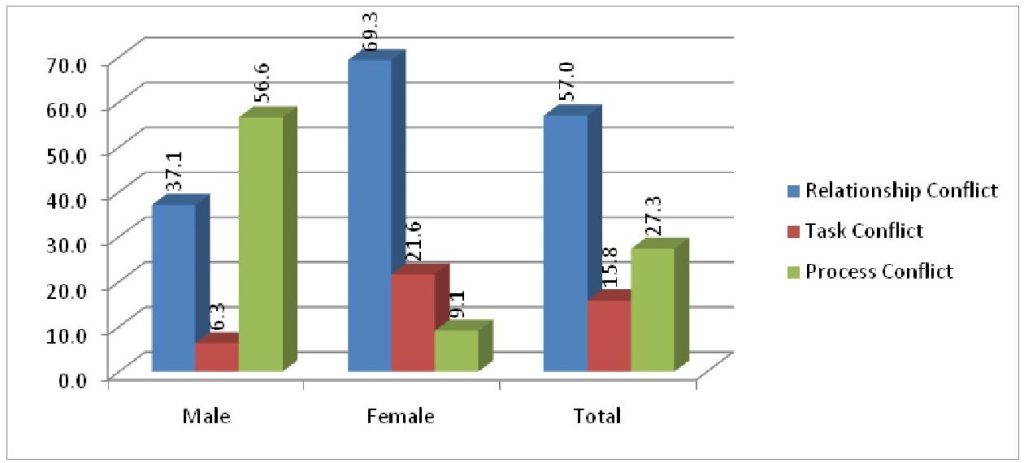

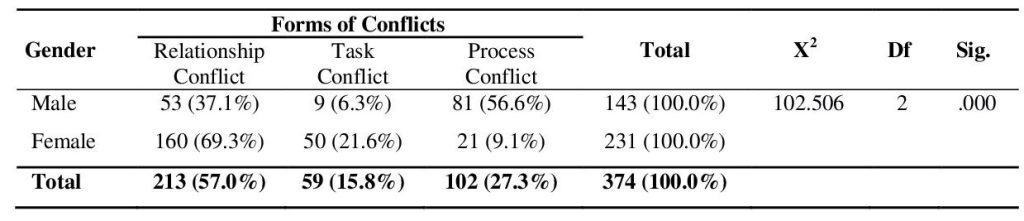

Figure 3. Gender Dimensions of Conflict among employees Data contained in figure 3 showed that there was variation in the dimension of conflict between male and female non-academic employees of public tertiary institutions. The data showed that as indicated by more than half proportion (56.6%) of the respondents, male employees were more inclined to ‘process conflicts’ compared to other forms of conflicts, while females were more inclined to relationship related forms of conflicts, as indicated by the highest proportion (69.3%) of the respondents. Further inferential test was conducted to determine if this result is statistically significant. The result of the statistical test is presented in table 2. Table 2. Relationship between gender and forms of conflicts among employees

The chi-square test was run to determine if there was an association between gender and forms of conflicts among non-academic employees in the selected tertiary institutions. Result of the test showed that a statistically significant relationship was found between gender and forms of conflicts among the non-academic employees. In other words, the form of conflict observed among the non-academic employees of public tertiary institutions in the South-East zone of Nigeria is significantly related to the gender of the employees. Effects of Conflicts among Employees This study equally tried to examine the perceived effects of conflicts among non-academic employees of public tertiary institutions in the South-East of Nigeria, taking into cognizance, the gender dimensions of the effects. Result of the analysis conducted on the responses gathered is presented in table 3. Table 3. Gender Dimensions on the Effects of Conflicts among Employees

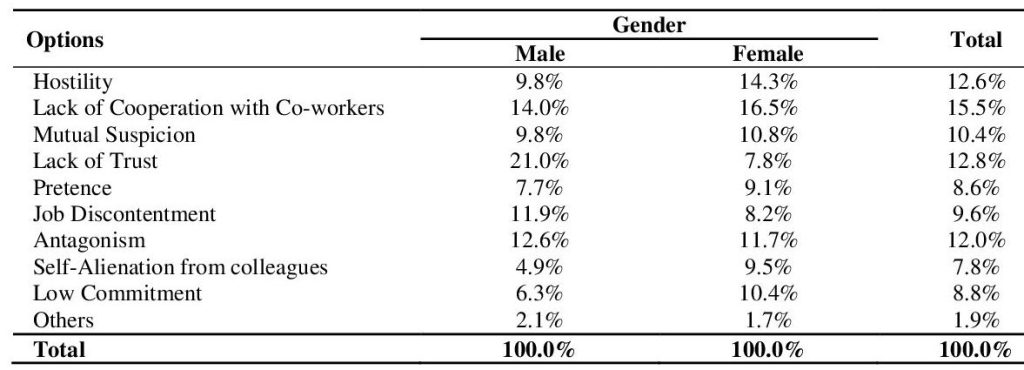

Data analysis as presented in table 3 showed that, in the overall, the effects of conflicts among employees manifest through lack of cooperation with co-workers (15.5%), lack of trust among themselves (12.8%), hostility (12.6%), antagonism (12.0%) and mutual suspicion (10.4%), among other latent effects. In terms of gender analysis, it was found that among the male employees, the major effects of conflicts on them include lack of trust (21.0%), lack of cooperation with co-workers (14.0%), antagonism (12.6%) and job discontentment (11.9%), while for the female employees, the observed effect include: lack of cooperation with co-workers (16.5%), hostility (14.3%), antagonism (11.7%), mutual suspicion (10.8%) and low commitment (10.4%), among other latent effects. Conclusion/Recommendations This present study investigated the gender dimensions of work-related conflicts among the non-academic employees in selected tertiary institutions within the Southeast of Nigeria. The findings obtained from a series of data analysis in this study suggest that gender dimensions to work-related conflicts among the non-academic employees within the context of public tertiary institutions in the study area are somewhat dynamic, with distinctions being observed in the forms of conflicts that occur among the female employees and conflicts that occur among the male employees. This implies that what generates conflicts among female employees is somewhat different from what generates conflicts among the male employees. While this present study does not offer a conclusive answer to everything connected to gender dimension in work-related conflicts, it has presented a research direction in an area of research that appears to be unexplored by previous organisational researchers. In this direction, it would be necessary to explore this study in more details in order to fill other gaps that are yet to be filled in relation to the theme. If policy makers especially within the context of the public tertiary institutions would take this study seriously, it would help them to understand the dynamics of work-related conflicts among employees as well as offer them the best approaches to address such conflicts for the overall productivity of their organisations. Based on the observations from the findings of this study, the following are recommended:

References Abolo, E. V., & Oguntoye, O. (2016). Conflict Resolution Strategies and Staff Effectiveness in Selected Federal Universities in Nigeria. Educational Planning, 23(3), 29-39. Amason, A. C. (1996). Distinguishing the effects of functional and dysfunctional conflict on strategic decision making: Resolving a paradox for top management teams. Academy of Management Journal, 39, 123-148. Anwar, N., Maitlo, Q., Soomro, M. B., & Shaikh, G. M. (2012). Task conflict and its relationship with employee’s performance. Interdisciplinary Journal of Contemporary Research in Business, 3(9), 1338-1343. Dennen, J. M. G. V. D. (2005). Introduction: On Conflict. The Sociobiology of Conflict. London: Chapman & Hall, pp. 1- 19. Gentry, W. A., Booysen, L., Hannum, K. M., & Weber, T. J. (2010). Leadership responses to a conflict of gender-based tension: A comparison of responses between men and women in the US and South Africa. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 10(3), 285-301. Guetzkow, H., & Gyr, J. (1954). “An analysis of conflict in decision-making groups. Human Relations, 7, 367-381. Ihuarulam, M. O. (2015). Management strategies of conflict between academic and non-academic staff of federal universities in Southeast Nigeria. Available at https://www. unn.edu.ng/publications/files/17807_management_strategies_of_conflict_between_academic_and_non-academic_staff_of_federal_universities_in_south_east,_nigeria.pdf Ihudiebube-Splendor, C. N., & Chikeme, P. C. (2020). A descriptive cross-sectional study: Practical and feasible design in investigating health care–seeking behaviours of undergraduates. In SAGE Research Methods Cases. https://dx.doi.org/10.4135/97815 29742862 Jehn, K. (1997). A qualitative analysis of conflict types and dimensions in organizational groups. Administrative Science Quarterly, 42, 530–557 Jehn, K. A. (1995). A multimethod examination of the benefits and detriments of intragroup conflict. Administrative Science Quarterly, 40, 256-282. Jehn, K. A., & Mannix, E. A. (2001). The dynamic nature of conflict: A longitudinal study of intragroup conflict and group performance. Academy of management journal, 44(2), 238-251. Ndum, V. E., & Okey, S. (2013). Conflict management in the Nigerian University system. Journal of Educational and Social Research, 3(8), 17-23. Omisore, B. O., & Abiodun, A. R. (2014). Organisational conflicts: Causes, effects and remedies. International Journal of Academic Research in Economics and Management Sciences, 3(6), 118-137. http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJAREMS/v3-i6/1351 Simons, T. L., & Peterson, R. S. (2000). Task conflict and relationship conflict in top management teams: the pivotal role of intragroup trust. Journal of applied psychology, 85(1), 102. Thomas, K. W. (1992). Conflict and conflict management: Reflections and update. Journal of Organisational Behaviour, 13, 265-274. Ugwuanyi, R. N. C & Idoko, N. A. (2012). Conflicts and conflict management in academic libraries: an imperative for a productive and stress free work environment. Bassey Andah Journal, 3(5), 1-9. Umo, U. A. (2014). Forms and sources of conflict in Nigerian educational system: the search for Nigerian Psyche. Global journal of educational research, 13(2), 101-108. *About the Authors: Dr Chukwujekwu Charles Onwuka (cc.onwuka@coou.edu.ng) is of Department of Sociology Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu University, Igbariam, Anambra State, Nigeria while Dr Emmanuel Echezona Nwokolo (ee.nwokolo@coou.edu.ng) and Sunday Chike Achebe (revachebe@yahoo.com) are of the Department of Psychology of the same university. |

||