International Journal of General Studies (IJGS), Vol. 2, No. 2, July-September 2022, pp. 119-141 https://klamidas.com/ijgs-v2n2-2022-08/ |

||

|

Recounting History through Pristine Settlements: A Study of Selected Basà Toponyms in Nasarawa and Toto Local Governments of Nasarawa State By Philip Manda Imoh & Friday Nyizo Dansabo* Abstract This paper studies Basà toponyms in Toto and Nasarawa local government councils of Nasarawa State. Every place name in most Nigerian and African settlements has narratives which constitute the symbolic historical narrative behind it. The study seeks to answer the question: What are the motivations and the narratives behind toponyms in Toto and Nasarawa local government councils of Nasarawa state? Ethnographic data for the study were obtained through interviews and metalinguistic conversations in Basà speaking domains of Toto and Nasarawa local councils. The investigation adopted the linguistic descriptive method using the Leipzig Glossing Rule to interpret the data obtained. The facts in this study show that, while various approaches such as oral history, archaeology and other scientific methods can be used by researchers to study toponyms, a linguistic approach can also be adopted as an alternative complement. The findings from this study show that place names are historical preserving strategies and tools among the Basà ethnic group in Toto and Nasarawa local government areas. The linguistic approach used in the study revealed that the place names examined in the study involves various grammatical structures through complex morphological processes to derive their surface forms. The commonest sources of nomination of Basà toponyms are geographical features, water bodies, vegetations, animals, ideology, personal names, ideophones, transfer of settlement names and social factors. The investigation unearths, reminds, teaches and preserves unknown stories encapsulated in these toponyms. Keywords: Basà, history, narrative, narrative, Nasarawa, place names, toponyms, toponymy and Toto Introduction Basà language is spoken in different locations in North Central Nigeria such as, the six area councils of the Federal Capital Territory; Kokona, Nasarawa, Toto and Doma Local Government Councils of Nasarawa State; Bassa, Dekina, Ankpa and Kotonkarfe Local Government Areas of Kogi State; Kontagora Local Government of Niger State; Agatu and Markurdi Local Government Areas of Benue State. Some of these locations are characterized by different dialectal variants, each is identified by a distinct name, but all varieties are mutually intelligible. Basà language is classified as belonging to Western-Kainji of Kainji language family also referred to as Rubasa (Basa Benue) (Crozier and Blench, 1992:32). Trends in African studies involve unveiling traces of African culture and heritage embedded in their naming traditions to recover and reconstruct the African heritage. In most parts of Africa, their names are sources of oral records that can be carefully studied to make some remarkable findings about them and their history. This study focuses on toponyms. Toponyms have durable or long life span which cannot be easily erased. Their durability makes them have fixed or permanent landmarks which, with time result in important information for cultural and historical studies. Batoma (2006) lists five facets of toponyms namely, geographical, historical, linguistic, symbolic and socio-political. This study focuses on the linguistic aspect. Toponymy is the study of place names (David, 2011). Toponyms are mainly used to identify and distinguish certain places from others. Toponymic onomastics studies place names and examines the history of individual names or of the names found in particular social groups to uncover the original meanings to establish their social or geographical distributional patterns (Nuessel, 2012). Generally, it reflects the nature of relationship language speakers entertain with space. People name virtually every portion of space regardless of shape, topography, location, etc. and grant it the status of an identified delimited entity. The choice of toponyms sometimes can be arbitrary or random but in most cases, intentionally and systematically motivated. The subjectivity of the practice is unveiled by different names given to different places which show association with concept, entities, geographical features, history, etc. Thus, place names most generally refer to different factors namely, natural features, fauna and flora, ethnicity, landscape, etc. Laaboudi & Marouane state that assigning names to places like cities, avenues and plazas is one of the widely adopted naming strategies that aim to establish a relationship of appropriation, affiliation or delimitation between people and space. “When people’s names are given to a place, the intention is either to honour the person whose name is given to the place or show a kind of affiliation of the place by the people who named it” (p108). Linguistically, place names are important because they unveil and preserve language identity of the communities who live or lived there. They indicate the language spoken in a particular area or region and show traces of the isoglosses between the communities and ethnic groups who speak different languages or dialects. This implies that the dominant place names from a particular language in a region or geographical area would show that inhabitants of such a place are or were members of that ethnic group or language. Also, toponyms from different languages show that different ethnic groups coexist or coexisted in the area. This can be supported by the claim of Curchi (2011) where he points out that toponyms tend to be conservative; remaining in use for centuries after their original meaning has been forgotten. He adds that they thus serve as linguistic fossils, preserving traces of all the language groups that settle there. Toponymy is very significant because most people view toponyms as mere labels convenient for users to identify features on the map or as sign posts. Place names, however are established part of linguistic, ethnocultural and historical features of a region. Handcock holds that toponymy is concerned with the origins and meanings of all geographical names and with the changes these names have undergone, in form, spelling and pronunciation. He further argues that the latter places place names into field linguistics. Generally, Africans commonly use various oral traditions such as culture, songs, narratives, language, names, naming traditions to preserve their history. This is very apt in the Basà toponymic situation. The significance or relevance of this study is the need to preserve the culture, ethnonymy, history etc. of the Basà people which reflect in their geographical or place names. Collecting, studying and systematizing the corpus will help to preserve them and transmitting information to subsequent generations. More importantly is the fact that they are unexplored areas in North Central Nigeria. Furthermore, in a disputed land situation, this information could serve as evidence that can be used to resolve the matter and determine the true owner. This study is important as it unearths and preserves the etymology of certain names that have survived over the years whose meanings were unknown. One unfortunate situation encountered in the course of our fieldwork was, some traditional leaders who are expected to be custodians of history, culture, tradition and customs do not know the meaning and history of their domains. This study will help to forestall such unfortunate trends. This study attempts to answer the following questions:

Literature Review Names exist as part of the socio-cultural setting of every society. Being part of the society that gives them, they act as a window through which the world is understood and appreciated (Mutunda, 2011). They are used as conduits of information, especially, on the society’s attitudes or observation towards the named (Mapara et al, 2009:9). Musonda, Ngalande & Simwinga (2019) states that it is important that one has a good knowledge of the imagery and metaphor of the language under consideration to appreciate their names. Toponymys include the names of all natural features such as rivers, mountains, islands, lakes, bays, etc. They also include man made places or features such as towns, cities, villages, parks, bridges, roads, etc. Handcock asserts that general categories such as families, places, such as islands or mountains are referred to as generics. Names of individual features (spoken, written or understood) are called specifics. This, he exemplifies thus, in the toponym ‘Signal Hill’ Signal is the specific part, whereas Hill is the generic. He says, the name St. John’s uses only the specific part of the toponym but a listener or reader is expected to know that the name refers to the place of a settled community, in this case, a city. He reveals that naming convention vary by language. In French, the word order permits the generic to occur first, whereas, in English, it is most common to put it last, though names which are of French in origin were adopted in English usage often retaining linguistic evidence of their initial form, e.g. Harbour Grace (originally, la Harvre de Grace) or Port de Grace. Studies on personal names and toponyms have been carried out in the onomastic literature in different disciplines such as linguistics: Akinasa (1980), Ubahakwe (1981), Oduyoye (1982), Essien (1986), Aceto (2002), Agyekum (2006), Merkel & Yakovleva (2008), Hardcock, (2011), Klugah, (2013), Agbo (2014) Mensah (2013), (2015), and (2017), Mensah & Ishima (2020), Okon (2017), Laaboudi & Marouane (2018), etc.; Psychology: Steele (1988), Steele & Smith (1989) etc. ; Anthopology: Bean 1990, Obeng (1998), Anderson (2004 & 2005), Ukpong (2007), Author (2015) & (2017); Sociology: Ngade (2011), Suzman (1994), Author (2016); Geography: Villette & Purvea (2018), Tent & Blair (2009), Luo, John & Wang (2009), etc. Imoh (2019) investigates the structure of Basà personal names, Imoh (2020) studies the ethnopragmatics of Basà personal names, Imoh & Dansabo (2020) ex-ray the sentential structure of Basà personal names, Imoh (2020) is on indirect communication strategy among the Basà people, Imoh (2021) studies the symbolism of Tìrìbì shrine naming practices and communication and Imoh & Dansabo (2021) investigate ethnopragmatics of death prevention names in Basà. The researchers carefully observed that most works are mainly in sociology, psychology, anthropology, geography, etc. though there are few on linguistics, both personal and toponymic, but none addresses any aspect of Basà toponyms. This serves as the motivating factor to fill the existing research gap and make a valuable contribution to the onomastic literature and scholarship in general. Toponyms are geographical names or place names applied to geographical features and settlements on the earth’s surface. Handrcock (2011) states that place names occur in both spoken and written languages and represent an important reference system of individuals and societies throughout the word. Specifically, toponymy refers to the study of geographical names of particular regions or territories. The term ‘toponym’ derives from the Greek word topos ‘place’ and onoma ‘name’. Handcock states that a toponymist will not only look at the meaning of a given name but also at the history of the area. He further argues that “Doing so helps to reveal the story behind the names” just as it is believed that “every name has a story to tell” (1). The Concept of Pristine Settlements The study on pristineness of place is quite scarce. Udoye (2017:33) claims that lack of interest in the study of pristineness is responsible for its dearth. Though scholarly studies on the subject matter were scanty, a few were found. The Advanced Learners Dictionary (2001) and Urban Dictionary define the concept as an adjective that means something that is fresh and clean as if new, not developed and changed in any way; left in its original condition. Other researchers define the concept as a place that is untouched or spotless (Nash 2012 and Paul 2013). This view is in support of Gibson (2011) who states that it is a place that is ancient, primitive, good, old, uncorrupted – an unspoiled beauty. Paul (2013) adds that ‘Pristine’ stands for an environment that is untouched by human hands and untouched over thousands of years. For the researcher, the conceptual relevanc of ‘pristineness’ is not the strict sense of spotlessnes as there is no place that is purely pristine; rather, it is pristineness in the context of the toponyms of the study areas. Methodology The methodological basis of this research is a complex linguistic approach to the study of regional toponymy. Techniques used in the study are: the method of scientific description, the method of semantic classification and etymological analysis without necessarily considering structural classification. The work on the complex analysis of this aspect of the Basà toponymy includes gathering of toponyms in the study areas, the linguistic aspect of the investigation (which incorporates etymology, semantics and structure, where applicable) and aspects of extralinguistics of the survey, namely, georeferencing, culture and historical information. The toponyms under study where collected from aborigines of Toto and Nasarawa local government councils of Nasarawa State, North Central Nigeria, through oral narratives. The study adopts a qualitative research method. We had to adopt this method only since there is no existing document where information can be retrieved either from missionary or ethnographic sources. The information was sourced by interviewing traditional leaders and elders who were purposefully sampled based on their knowledge of the study areas and willingness to participate. The researchers prepared an interview guide to steer the course of the interview. The informants were contacted to arrange a possible rendezvous for interview. Probing questions were further asked where necessary in order to elicit further information and seek clarifications on issues that were not clear. Each interview session was recorded in our field notes. The informants and researchers spoke Basà, their native language which necessitated the need to transcribe the raw data for analysis. Recording Toponyms A major bottleneck in place names is recording names used in regions or communities by consulting older residents who either invented the names or inherited them from their older generations. Handcock (2011) states that once the names are recorded and defined by location (geo-positioned, given a geographical position reference) names are securely preserved and can be considered for official use. Toponymic records not only assist in expanding data bases for mapping and other practical purposes such as mining exploration, travel and recreational uses, search and rescue operation, emergency measures, national security and land use planning, it is also effective in preserving and securing vital information about culture, history which can be lost with the death of the elders who are custodians of history and the demise of traditional life orchestrated by modernity. This is one of the various reasons why the researchers regard the recording of toponyms as study that has to be undertaken now as an important aspect of cultural heritage and identity. This view agrees with the assertion of Handcock (2011) which argues that “Traditional names in their cultures had to do with survival, identifying hunting and fishing sites, sacred places and providing other important information about history of their respective areas” (3). He (Handcock) states that toponymy, thus, provides a main link to the ancestors and ancestral lands and is a central theme in the history of a people. Analysis of Basà toponyms Basà is a tonal language characterized by three register tone levels. Tones in the language are phonemic, that is, tone variations cause meaning change in the language and it is also grammatical. Thus, the high tone is marked with an acute tone, the low tone with grave tone and the mid tone unmarked. This section discusses the processes of Basà place names in Toto and Nasarawa local government areas. Place names in these areas bear strong traces of the Basà language that transited through them. This supports the assertion of El Fassi (1984:18): The various civilizations which succeed one another in Morocco did not leave any significant traces in its toponymy. It can even be said that at present, there are practically no names of foreign origin to be found, except those of Phoenician or Carthaginian origin. These languages are closely related to Berber. The names of many towns and villages were changed by the French, but as these changes were not spontaneous, being imposed by the colonial powers, foreign names disappeared as soon as independence was proclaimed and the places reverted to their old names, which had never been forgotten by the inhabitants. Toponyms of foreign origin do not prominently feature among regions or places populated or dominated by the Basà ethnic group. In our search, even where some place names do not seem to have features of the Basà language or bear some linguistic affinity, going through their etymology, it was discovered that the distortion resulted from inability of either the government officials, the educated or settlers pronouncing them correctly. All appellative aboriginal names in Basà feature their natural environment and geographical features, personalities, history etc. In what follow, data analysis and discussion of data are presented. Table 1. Basà Toponyms as personal names

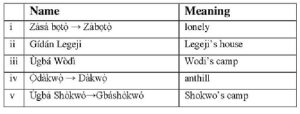

In Table 1, the toponyms are derived from personal names; Ọ̀dàkwọ̀ (ant hill) derives a personal name Dàkwọ̀ by eliding the initial sound. Most of the place names that are personal names are names of the first occupants of the named settlements. These names tell a lot of stories about the founder and the formation of the place. The story is preserved generations after the founder’s death and it is passed from generation to generation. Tent & Blaire (2009, 2013) call this type ‘eponyms’, that is, commemorating or honoring a person or other named entity by using a proper name as a place name. They exemplify this with names like Maria Island, Tryall Rocks, etc. Fauna which refers to all the animal life present in a particular region or time is also used as a productive source of place names in the Basà toponyms. The choice of animal names as place names is contained in the story of the named place. This is also used to preserve the rich history of many places in the Basà areas and regions or villages. Examples of this category of Basà toponyms are in table 2 below. Table 2. Basà Toponyms as animal names

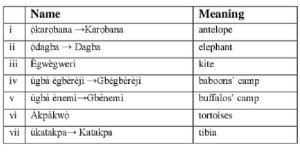

Table 2 comprises names of animals used as toponyms. As earlier noted, toponyms are history preserving tools in the Basà ethnic group because they are used to mark important occurrences or contain certain narratives about the people, past events, etc. In table 2 (row i), Karọbana (antelope) is so named because the place had a dominant presence of antelopes before and during the early periods of settlement. This also applies to the data I rows ii-vi. The animal names used as toponyms in these settlements had a history of dominance of the animals concerned. Katakpa in row vii has a different narrative. Our source gave a narrative of a hunter who shot an elephant. The elephant escaped with gunshot wounds and latter died. The hunter did not find it until it had decomposed. When he found the rotten body of the elephant, he cut the tibia as an evidence of his claim and marked a particular location where they eventually settled. The name Katakpa (tibia) became the name of the settlement. The following examples (table 3) present place names based on vegetation species and these are called phytonyms (phytotoponyms). This floral category comprises different trees and vegetations used for their economic value, fertility, spiritual protection, timber, etc. Table 3. Basà Toponyms as plant names (phytonyms)

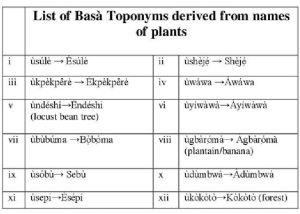

All the data in table 3 are sourced from various economic trees. Èsúlè, Àwáwa, and Sebù are strong and quality economic trees used for timber; Shẹ̀jẹ́ is a local economic tree used for animal fertility, spiritual protection etc. It can render the user invisible against physical and spiritual forces or aggressors. It also serves as a spiritual herbicide against pest, especially yam pest. Èndéshí (locust bean tree) is an economic tree used to make local seasoning for preparing local delicacies which are said to be very nutritious and rich in protein. Èkpèkpêrè is a common fruit commonly known as ‘ogbono/ogbolo’ used to prepare slimy soup commonly called ‘draw soup’ in Africa. This tree is also a good source of timber. Àgbàrό̣mà (plantain/banana) is a very common sweet and succulent fruit in Africa; Èsépí is a thorny shrub while Kòkòtò is a thick forest. The vowel replacement or modification and elision are derivational processes used to derive proper names from common nouns in the language. The narratives behind the derivation of these names were that at the point of migration these were the dominant trees found in the named locations. There is another category of names found during our field research. Those are names sourced from the water bodies found around the named settlements. The Basà people value water a lot and water plays a major role in the choice of a settlement. This category can be exemplified in table 4 below. Table 4. Toponyms as Hydronyms

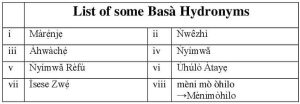

Màrẹ́njẹ in (i) is descriptive of the crystal nature of the water body in question used to name the settlement. Rẹ́njẹ́ is an adjective that means clean, see-through or crystal. It derives a nominal by prefixing the base with a derivative affix mà-. The Basà language has different names for different water bodies. Ǹwêzhì and Ǹyímwǎ are sources of water from where the toponyms are derived. Data (v-vii) are descriptive names that indicate the inherent characteristics of the water bodies. These compounds are endocentric because the leftmost elements are basic (which Handcock (2011) refers to as generics) described by the rightmost elements which (Handcok (2011) refer to as specifics). In (v), Rèfù ‘river’ describes the largeness of Ǹyímwǎ which is distinguished by its size and width or larger than the usual Ǹyímwǎ. In Ùhúlò Àtayẹ ‘rocky stream’ Ùhúlò ‘stream’ is endocentrically described by Àtayẹ ‘rocks’ to typify or described the attribute of the named stream. These two reveal that toponyms can show association with a variety of referents such as time, event, certain physical features of the place etc. What is common in this corpus is that toponyms usually reflect what people perceive as the outstanding or important features of the place. Example (viii) Ménimòhilo ‘farm water’ shows the description of the basic word by another noun or what the possessive word possesses as its distinctive feature i.e. mèni is basic and generic but òhilo ‘farm’ is the possession. These are what tent and Blair (2009;2011) in their taxonomy of toponyms classify as descriptive indicating inherent characteristics of the place name e.g. Wide Bay, Three Mile Creek etc. and associative i.e. referring to something which is always associated with the place name or its physical context e.g. Shark Bay Telegraph Point etc. In our field work, we found a category of names that are ideophones. Ideophones are vividly depicted sensing experience with marked forms. They abound in most Nigerian and African languages (Niger-Congo, Afro Asiatic) and beyond; for instance, Dravidian, Austro-Asiatic as well as languages such as Japanese, Korean, Turkish and Basque. It is traced to Bantu linguistics but applicable to all languages. In Japanese linguistics, it is referred to as ‘mimetics’ and ‘expressive’ in South and Southeast Asian linguistics. In Basà, they have features of adjectives but are not purely adjectives. A common feature they share with adjectives is, they show attributes or describe things, texture, feelings, utterances etc. but differ in that they are used to imitate sounds or make onomatopoeic expressions etc. This category of names is not common, but a few were elicited in our field work. Table 5. Toponyms as Ideophones

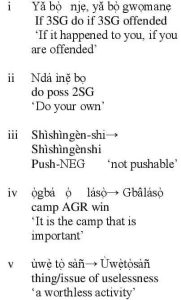

Kòngbò is an ideophone used to make an expression of something heavy or imitate a heavy sound or explosion, or something unbelievable e.g. the demise of a powerful ruler, an unbearable and unbelievable happening, an explosive sound etc. Jérényá is used to express tightness, tininess, narrowness or firmness. These names have historical narratives that are passed from older generations to the younger ones. The people consulted have common understanding about the context of the names but the story responsible for their nomination were unknown, that is, the names are surviving but their histories are endangered or lost. This was an endangered aspect of names we encountered as some names exist without the knowledge of their meaning and etymology. What is responsible for this unfortunate loss is, custodians of the oral history of these settlements did not pass to the succeeding generations the information they inherited from their ancestors. Indirect communication is also used to generate toponymic names. Indirect communication is acting out rather than directly saying what a person is thinking or feeling using facial expression, tone or voice and or gestures. It means, the speaker doesn’t explicitly state what their intentions or feeling are; instead, they rely on other forms. Indirect communication in Basà Onomastics is very productive, especially in zoonyms and toponyms (see Imoh 2020). This category can be furnished with data in table 6. Most of them are in sentential forms especial statement and command. Table 6. Toponyms as indirect communication

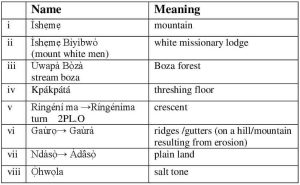

The statement in data (i) is made by the founder of the settlement who equally named it. It has a deep meaning which is ‘whatever someone says is based on their experience or what happened to them, which may be unknown to others’ It implies that the ones that left their old settlement know what is responsible for their migration and relocation. Data (ii) is an imperative. It is in response to an unknown antagonist who probably spites the protagonist. The construal of this sentence does not have a predetermined meaning, rather, it is open ended, but one common interpretation to it is the fact that the protagonist uses the name to respond to those who are jealous or an antagonist. Datum (iii) (Shìshìngènshi) indirectly addresses the antagonist or aggressor’s hostility. The story underlying the name as was narrated is that, two ethnic groups contested two settlements. The perlocutionary statement made by the avenger or protagonist is directed to the antagonist/aggressor warning them that their patience which had been taken for granted is exhausted; any further contempt/aggression shall be meted with stiff resistance. It indirectly draws a battle line between two warring parties dishing out a stern warning as a threat. (iv) ọ̀gbá stands for a number of camps in Basà. In this context, it stands for a fighting ring or a battle ground. From the narrative, the speaker is likely to be the protagonist and the statement targeted at the antagonist. It is meant to caution the antagonist who underrates the capacity of the protagonist that one’s bragging can only be determined on the battle ground where physical conflict or fight takes place. The name Ùwẹ̀tọ̀sàñ in (v) derives from a disagreement between an antagonist and a protagonist. The name is clearly characterized by contempt and an indirectly communication either to offend or vindicate. Our informants were not certain whether or not it was the antagonist or protagonist that generated the name, but share the same understanding that the name implies a verbal contempt meant to vindicate an antagonist. Geographical features such as mountains, valleys, plains, deserts, basins, rivers, soil, natural vegetations etc. as demonstration in the foregoing discussion are a rich sources of Basà toponyms. Most of these names are evaluative in nature as they reflect a strong connotation associated with the place. Examples of geographical features can be shown in table 7 below: Table 7. Toponyms as Geographical Features and Description of Locations

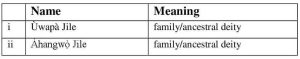

Example (i) means mountain, the settlement is located on a hilly place or close to a mountain or hill which is higher above the surroundings. The place name derives from the geographical feature or the topography of the place. Example (ii) is eponymous in nature because it commemorates or honours the person (white man) by using their identity to show the attributes of ìshẹmẹ ‘maintain’. This could result from the reverence the Basà people have for white people. Ùwapà Bọ̀zà in (iii) shows association with a referent in wapà ‘stream’ which is compounded with an endocentric component Bọ̀zà; a kind of tree which bears a red fruit used by young women to make cosmetic tattoo and beatification. It was also reported that the milky liquid from the fruit can be mixed with soap for bathing. It makes the skin fresh and beautiful. The narrative from the field states that this particular tree was common in the area at the time of settling. The place also has a stream (Ùwapà), but the stream featuring as the head of the compound stands for forest (of Bọ̀zà) which is used to show the attribute of the head word. In (iv), Kpákpátá ‘threshing floor’ it is a hard, level surface on which farm produce, especially grains are threshed with a flail. It is a place of separation where the harvest is prepared by separating the grain from the chaff. This settlement is so called following the attributes of the land i.e. being hard and level surface. Data (v) Ríngéníma ‘turn’, an imperative addressed to second person plural is named following the geographical nature or the topography and physical features of the place i.e. being a crescent. Example (vi), Gaùrá ‘ridge’ or ‘gutters’ is so named considering the ridge-like nature or gulleys on the mountain caused by erosion. The name of the settlement derived from the physical impression erosion made on the mountain. Àdâsọ̀ ‘plain land’ derived from ndàsọ̀ which is an ideophone describing a plain topography. The place is occupied by another ethnic group whose phonotactics requires vowel insertion for proper names that are non-indigenous beginning with an onset. The narrative from our field report claims that this factor was responsible for the corruption of the original name which was eventually adopted and gazetted. Finally, Ọ̀hwọla in (ix) is ‘salt stone’ which always attracts animals like antelopes, rabbits and other animals that leek it. It is so named considering the predominance of this mineral resource in the area. There was a category of names elicited during our field work which were names of deities. This category was very scanty and uncommon. They are not normal or conventional settlements like others but sacred places where priests dwell to consult spirits, ancestors or deities. These people dwell here to serve as intermediaries between mortal men and spirits, ancestors or deities. They are highly pristine because they are guided by ancestral rules that are not concerned or affected by modernity and civilization. Examples: Table 8. Toponyms as names of deities

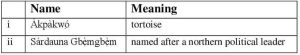

The two examples in table (8) are sacred places made up of endocentric compounds. In Basà, the compound is headed by the leftmost element which also determines headedness (see Imoh 2017). Thus, the basic element is the leftmost element whereas the satellite at the rightmost edge. What they have in common in the fact that they are dedicated to specific deities or ancestors and are highly venerated sites. In the Basà language, the word ùwapà means ‘water body’ in general or could mean ‘forest’. In Africa, secret places are located in the forest and by the side of a water body. In (i), it refers to both. In (ii), Àhangwọ̀ refers to a sacred camp which is located not too far from general human settlement and not necessarily by the river or water side. Both of these sacred places are settlements of family ancestral deities meant for family protection. They only differ in that (i) is only owned and usable within by the family or extended family whereas, (ii) can be extended to matrilineal family members. Some place names can be transferred from their original base to a new settlement when a segment or the entire people of the old settlement move to a new location. In this instance, the name of the original place is reduplicated or morphologically modified or extended to make a little contrast with the original location. Instances of this category are demonstrated in table 9. Table 9. Toponyms as transferred names

The principle of shift i.e. using a toponym in whole or part from another location or remote place e.g. New Orleans, New England etc. (Laabondi & Maronane 2018:177) is also practised in Basà toponyms. The ethnic group has a very rich migratory history and some families or settlements moved with their old place names. In a situation where a section of people remains in their original ancestral land and another section moves out, it usually results in a duplication of the original ancestral place name, but where all occupants move together, the name is transferred to the new location, either with slight modification or none. A good example of this are toponyms like Àkpàkwό̣ ‘tortoise’, in (i) which means, at the time of founding the original settlement, there were many tortoises and Sàrdauna Gbẹ̀mgbẹ̀m in (ii) taken from Sàrdauna etc with slight modificatio. The original etymological factors may not be applicable to the new location. The main intention is to preserve identity and history or those factors for which they are known. Conclusion This study has researched into the motivation for toponyms and their typological categorization. The Basà toponyms as demonstrated in this study are oral records which contain the historical information about the people, migration, challenges, struggles, belief etc. These names can scarcely be extricated from the people and their history. For some, toponyms are part of not only their history but their culture, experience, politics, and identity as they constitute fossilized landmarks whose durability make them important sources of data and information about their ancestry. In the study, the commonest morphological processes toponyms are constructed in this study are elision (of the initial vowel sound of the source lexeme before deriving the surface form) and compounding. Only few transfers are attested. This study discovered that the commonest sources of nomination of Basà toponyms in the study areas are: features of geographical areas, that is, the characteristics of the area named; water bodies; vegetation or plant species; animals (flora and fauna); ideological and social factors; personal names, ideophones, deities and transfered names. These are the main sources where topo-lexemes are generated. In general, the nomination of these names is within the dynamics of the society or community in question. The understanding of these names can lead to the appreciation of the history of the named place and the people. This work can be replicated in other languages as a way of obtaining vital information, make input to the onomastics literature and preserve the ancestral history that may be lost with the demise of the custodians of oral and traditional history. References Aceto, Michael. (2002). Ethnic personal names and multiple identities in anglophone Caribbean speech communities in Latin America. Language in Society.31, 57-608 Agyekum, Kofi. 2006. The sociolinguistic of Akan personal names. Nordic Journal of African Studies 15 (2) 206-235. Akinnaso, Niyi F. 1980. The sociolinguistic basis of Yoruba personal names. Anthropological Linguistics. 22(7), 275-304. Akung, Jonas. and Abang, Oshega. (2019). I cannot baptize satan: The communicative import of Mbube death-prevention names. Sociolinguistic Study 13 (2-4)295-311. Anderson, John. (2004). On the grammatical status of names. Language. 80, 435-474. Atoma Batoma (2006). African ethnonyms and toponyms: An annotated bibliography. Electronic journal of Africana bibliography. 10 (1), 1- 40. Bean, Susan. (1990). Ethnology and the study of proper names. Anthropological Linguistics, 22 (7), 305-316. Beattie, John M. (1957). Nyoro personal names. Uganda Journal 21.348-47. Croizer, David. H. & Blench, Roger. M. (1992). An index of Nigerian languages (2nd edition). Dallas: SIL. Crystal, D. (2008). A dictionary of linguistics and phonetics. Oxford: Blackwell. Curchin, L. A. (2011). Naming the provincial landscape: settlement and toponymy in ancient Catalunya. Hispania Antiqva XXXV, 301-320. Daouia Laaboudi and Mohamed Marouane (2018). Ait and Oulad toponyms: Geographical distribution and linguistic implication. Journal of applied language and culture studies. 1, 107- 131. David, J. (2011). Commemorative place names: Their specialty and problems. Names journal of onomastics. 59 (4) 214-228 Diala, Isidore. (2012).Colonial mimicry and postcolonial re-membering in Isidore Okpewho’s Call me by my rightful name. Journal of Modern Literature, 36 (4) 77-95. Dixon, R. (1964). On formal and contextual meaning. ActaLinguistica 14, 23- 46. Epstein, Edmund. and Kole, Robert. (1998). The language of African literature. Trenton, NJ: African World Press. Elema Merkel and Lyubov Yakovleva (2008). Experiment of South Yakutia toponym’s lexicographic description. EDP science. Available at: https:// doi.org/ 10.1051. El Fassi, M. (1984). Toponymy and ethnonymy as scientific aids to history. African ethnonym and toponyms. Paris: the united nations educational, scientific and cultural organization. Essien, Okon. (1986). Ibibio Names: Their structure and their meanings. Ibadan: Day Star Press Finnegan, Ruth. (1976). Oral literature in Africa. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Gordon Handcock (2011). An introduction to geographical names and the Newfoundland and Labrador geographical names board. Unpublished report. Haviland, William, Prince Harald. and McBride, Bunny. (2013).Cultural anthropology: The human challenge. Stanford, CA: Cengage Learning. Hussein, Riyad. (1997). A sociolinguistic study of family names in Jordan. Grazer linguistiches studien 4, 25-41. Imoh, Philip Manda and Dansabo, Friday. N (2020). The ethno-pragmatics of Basà personal names. The Griot. 3, 182-202. Imoh, Philip Manda. (2019).An onomastic study of the structure of Basà personal names ANSU Journal of Language and Literary Studies (AJLLS).1 (5) 56-72. Imoh Philip Manda. (2020) Onomastics: An indirect communicative strategy among the Basà people. Journal of the Linguistics Association of Nigeria Supplement iv, 214-232. Imoh Philip Manda and Friady Nyizo Dansabo (2021). Basà sentential names: A brief descriptive study. Journal of the institute for Nigerian languages. 83-98. Imoh Philip Manda and Friady Nyizo Dansabo (2021). Personal names: An ethno-pragmatic study of Basà death prevention names. Nasara journal of humanities. 10(i), 146-157. Jauro, Barnabas L., Ngamsa, John. & Wappa. John Peter. (2013). A morphosemantic analysis of the Kamue personal names. International Journal of English Language and Linguistics 1, 1-12. Julia Villette and Rose S. Purves (2018). Exporing microtoponyms through linguistics and geographic perspectives. Agile. 2-4. Koopman, Andrian. (1990). Some notes on the morphology of Zulu clan names. South African Journal of African Languages. 4.1: 333-37. Lacastro, Virginia (2012). Pragmatics for language educators: A sociolinguistic perspective. New York: Routledge. Lyons, John. (1977). Semantics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Maenetsha, Kholofelo. (2014). To the black woman we all Know. Cape Town: Modjaji Books. Mandende, Itani Peter. (2009). The study of Tshivenda personal names. Pretoria: University of South Africa. Mapara Jacob (2009). The indigenous knowledge system in Zimbabwe: juxtaposing post-colonial theory. The Journal of Pan African Studies, 3, 139-155. Mapara, Jacob. (2013). Shona sentential names: A brief overview. Mankon, Bamenda: Langaa Research and Publishing. Mashiri Pedzisai, Chabata, Emmanuel and Chitando, Ezra. (2013). A sociocultural and sociolinguistic analysis of postcolonial naming practices in Zimbabwe. Journal for Studies in Humanities and Social Sciences. 2, 163-173. Mensah, Eyo. (2013).The structure of Ibibio death prevention names. Anthropological Notebooks.19, 41-59. Mensah, Eyo and Offong, Imeobong. (2013). The structure of Ibibio death prevention names. Anthropological Notebook, 19 (3): 41-59. Mensah, Eyo. (2015). Frog, Where are you?: The ethnopragmatics of Ibibio death prevention names. Journal of African Cultural Studies 27, 115-132. Mensah, Eyo. (2017). Proverbial nicknames among rural youth in Nigeria. Anthropological Linguistics. 59, 414-439. Mensah, Eyo. (2020). Name this child: Religious identity and ideology in Tiv personal names. A Journal of Onomastics 68. 1, 1-15. Mercy Adzo Klugah (2013). Recounting history through linguistics: A toponymic analysis of Asogli migration narratives. African journal of history and culture. 5(8), 151-159. Musonda Chola, Ngalande Sande and Simwinga John. (2019). Daring death among the Tumbuka: a socio-semantic analysis of death-related personal names. International Journal of Humanities Science and Education (IJHSSE). 6,7: 109-120. Mutunda, Sylvesta. (2011) Personal names in Lunda culture milieu. Arizona: university of Arizona. Moyo, Thema. (1996). Personal names and naming practices in Northern Malawi. Nomina African. 10.1 & 2: 10-19. Mwangi, Kinyanjui Peter. (2015). What’s in a name?: An exploration of Gìkuyu grammar though personal names. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science.5,259-267. Nash, J. (2012). Pristine toponyms and embedded place names on islands. Names journals of onomastics. 23, 259-271. ` Ngade, Ivo. (2011). Bakossi names, naming culture and identity, Journal of Africa Cultural Studies. 23(2) 111-20. Nuessel, F. (1992). The study of names: A guide to the principle and topics. Westport, CT: Green Press. Obeng, Samuel G. (1998). Akan death-prevention names: A pragmatic and structural analysis name 46, 163 -187. Oduyoye, Modukpe. (1982). Yoruba names: their structures and naming. London: Karnak House . Olawale, F. (2005). News journal community advisory board. Ibadan: Heinemann. Omachonu, G.S. & Onogu W. S. (2012). Determining compoundhood in Ígálà: From universal to language specific focus, Journal of Universal Language 13-2, 91-117. Raymond Yahaya opega (2018). Structure pragmatics and meaning of Igala personal names. A PhD thesis submitted to the Dept of English language, University of Nigeria, Nsukka. Plank, Frans. (2011). Differential time stability in categorical change: Family names from nouns and adjectives illustrated from German. Journal of Historical Linguistics 1,269-292. Sagna, Serge and Bassene, Emmanuel. (2016). Why are they named after death? Name giving, name changing and death prevention names in Gújjolaay Eegimaa (Bangul). African Language Documentation and Conservation, 10: 40-70. Searle, John. (1958). Proper names. Mind. 67:166-173. Steele, Claude M. ( l988). The psychology of self-affirmation: Sustaining the integrity of the self. Advances in experimental social psychology. 21, 261-301 Steele, Kenneth & Smithwick, Laura. (1989). First names and first impression: A fragile relationship. 21:517-523. Suzman Susan M. (1994). Names as pointers: Zulu personal naming practices. Language in society 23, 253–72. Tent, J. and Blair, D. (2009). Motivations for naming: A toponymic typology. ANPS Technical paper II. South Turramurra, NSW: Australian National Place names Survey. Ubahakwe Ebo. (1981). Igbo names their structures and their meanings. Ibadan: Day Star Press. Udo, Edet (1983). Who are the Ibibio? Onitsha: FEB Publishers Limited. Udoye, Ifeoma Emmanuella (2017). Anthronomastics study of Igbo toponyms in pristine and non-pristine areas of Anambra state. A PhD thesis submitted to the Department of Languages and Linguistics, Nasarawa State University, Keffi. Ukpong, Edet. (2007). An inquiry into culture: Ibibio names. Uyo: Dorrand Publisher. Wei Luo, John F. Hartmann & Fahui Wang (2009). Terrain characteristics and Tai toponyms: A GIS analysis of Mang, Chiang and Viang. Geojournal. DOI 10.1007/s10708-009-929-8 *About the Authors: Dr Philip Manda Imoh (philip manda@ nsuk.edu .ng) & Friday Nyizo Dansabo (Friday dansabon @nsuk. edu.ng) are of the Department of Languages & Linguistics, Nasarawa State University, Keffi, Nasarawa State, Nigeria. |

||