|

Introduction

The insurgency in Northern part of Nigeria threatens security not just in Nigeria but in the Sub-Sahara region and the international community at large. The militant Islamic group known as Boko-Haram was formed in the year 2001 by Mohammed Yusuf and their activities have grown wide in terms of capabilities (the use of suicide bombers and improvised explosive devices), membership (which includes foreign fighters from Chad, Mauritania, Niger, Somalia and Sudan) and the formation of splinter factions. The most prominent of these is Ansaru (its full Arabic name is Jama’atu Ansarul Muslimina Fi Biladis Sudan, which means “Vanguards for the protection of Muslims in Black Africa’’ which was founded by Abu Usmatul Al-Ansari in January 2001 and was seen to be an offshoot of Boko-Haram (Baffaello & Sasha, 2015). The activities of this group went viral within the Northern part of Nigeria with their frequent and sophisticated attacks which have steadily grown viral.

The term ‘Boko-Haram’ which means Western education is forbidden is agreed to be resurrection of the historical evolution of Islamic fundamentalism which started right from the time of Usman Dan Fodio. The notion of Jihad in Nigeria has a long historical root, in spite of the fact that Kalu (2004) reported that nine Jihads occurred before the 19th century, most scholars agreed that it was the Usman Dan Fodio Jihad that accounted for the spread of Islam in Nigeria (Yusuf, 2007; Christelow, 2002).

Between 1802 and 1812, Usman Dan Fodio launched a Jihad and ultimately founded the Sokoto Caliphate that spanned Northern Nigeria and part of Niger. Usman Dan Fodio’s social and political revolution against what he saw as greed and violation of Sharia law by African Muslim elites was widely popular, and the Caliphate represented an Islamic banner of resistance to colonial conquest, the rejection of secular government, and the regional net-working of Islamic movements in Nigeria and beyond (Abiodun, 2009). As time goes on, the rapid growth of Islamic revivalism actually laid a foundation for contemporary radicalism in Northern part of Nigeria. However, the goal and objective of Boko-Haram is primarily to establish an Islamic rule throughout Northeast part of Nigeria on the assumption that Nigerian government is corrupt and operate in accordance with Western principles and values. Sharia law therefore will be a guiding principle which will save the dying system because, to them, Islam is just and holy. However, Taiwo & Olugbode (2009) pointed out that while the exact date of the emergence of Boko-Haram is controversial, Colonel Mohammed Yerima, a spokesman of Nigerian military claimed that Boko-Haram has been in existence since 1995 with the name ‘’Ahlulsunnawal’jama’ah which is the largest group of Muslims whose beliefs and teachings are truly in accordance with Islam (Abugbilla, 2017) and it was said to have been originally led by Abubakah Lawan, who left the country later to study at the University of Medina in Saudi-Arabia (Onuorah, 2012). Though, what is certain is that Boko-Haram prospered and was widespread under Mohammed Yusuf’s leadership, a Salafist who was strongly and highly powered by Ibn Taymiyyah (Johnson, 2012).

However, the emergence and uprising of Boko-Haram from 2009-2014 took over 10,000 lives (Okeke, 2014) before it was put to a halt by Nigerian military forces in which the group lost its dynamic leader Mohammed Yusuf who had already named his successor, Abubakar Shekau, before his death. Boko-Haram was believed to have died a natural death after about a year of long silence but surprisingly resurrected and got into action in 2010 with brutal and massive killing, bombing and wanton destruction of lives and properties under Abubakar Shekau’s regime.

Boko-Haram terrorism has remained a thorn on the flesh of the Nigerian nation since 2009. This group deployed and adopted a holistic approach of terrorizing the world as the most effective method to achieving their aims. The incessant shooting at targeted churches, bombing in market places and parks, schools and government established institutions by this militant Islamic group with the aim of over throwing the government which they believe is corrupt created a state of uncertainty and this undermine the collective national security of the country. Based on the foregoing, the study aims at examining the impact of Boko-Haram activities as an Islamic fundamentalist group and how it poses a threat to collective national security.

Theoretical Framework

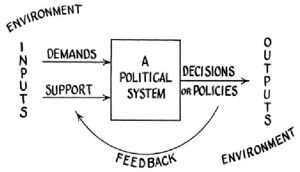

This work adopted David Easton’s Systems theory as the framework of analysis. Systems analysis, which was influenced by the Austrian Canadian biologist Ludwig von Bertalanffy and the American sociologist Talcott Parsons (1902–79), is a broad descriptive theory of how the various parts and levels of a political system interact with each other. Systems analysis studies first appeared alongside behavioral and political culture studies in the 1950s. A groundbreaking work employing the approach, David Easton’s The Political System (1953), conceived the political system as integrating all activities through which social policy is formulated and executed—that is, the political system is the policy-making process. Easton defined political behaviour as the ‘‘authoritative allocation of values,’’ or the distribution of rewards in wealth, power, and status that the system may provide.

In theory application, David Easton’s Systems theory wields strong explanatory power on Boko-Haram terrorism and the counter-terrorism efforts of the Nigerian state. The activities of the terrorists constitutes an environmental disturbance to the Nigerian political system, whereas the counter-terrorism strategies of the Nigerian state represents the response by the political system to the disturbance. The NACTEST strategy of counter-terrorism in Nigeria is an eminent output by the Nigerian political system in response to the destabilizing tendencies of the Boko-Haram terrorism to the system. The strategy involves unilateral actions by the Nigerian political system against the terrorism, and also collaborative actions with other political systems.

Easton argues that the political system is separated from another system by means of boundaries. But these boundaries are difficult to identify as the political system interacts with other systems through the means of exchange and interaction.

David Easton argues further that a political system begins functioning as a result of inputs received from the environment. Once input is received by the system, it begins processing the inputs which is known as the conversion process. The conversion process converts the input into output in the form of rules to be enforced and policies to be implemented. The output affects the environment and even modifies the input. Accordingly, the NACTEST strategy of counter-terrorism is geared towards degrading Boko Haram, i.e. effecting a change in the environment, and also modifies the input especially as a feedback.

David Easton’s Model of a Political System

Source: Easton’s 1957 article “An Approach to the Analysis of Political Systems”, p. 384

Conceptual Clarification

Terrorism

Jekin (1982) argues that the main problem in conceptualising or defining the term “terrorism” is political in nature and the major political problem in the definition terrorism surely lies in the decision when to differentiate or discern ‘terrorist’ from freedom ‘fighter’ or differentiate between ‘terrorism’ and war of ‘liberation’ (Dugard, 1974). Freedom fighter falls under jus ad bellum while terrorist do not. The term terrorism according to United States Federal Law connotes premeditated, politically motivated violence perpetrated against non-combatant targets by sub-national groups or clandestine agents, usually intended to influence an audience. Over the years, terrorism has been with us for centuries and it has attracted a lot of attention because of its dramatic character and its sudden, often wholly unexpected occurrence. It has been a tragedy for the victim but seen in historical perspective it seldom has been more than a nuisance. Terrorism is therefore one of the major method of operation use by radical Islamic fundamentalist because all their activities is geared towards militancy with their target of a radical and selfish change.

Terrorism has often been defined as violence or threat of its use, especially bombing, kidnapping and assassination carried out for political purposes as well as the use of violent actions in order to achieve a political aims or force a government to act (Kache, 2008). Terrorism is therefore a complex subject because it combines so many different aspects of human experience, like military strategy, psychology, politics, and history etc. Not all violence is terrorism but all terrorism involves violence. It is characterized by the use of violence with the expressed desire of causing panic or terror in the population. Many terrorist groups have been engaged in one struggle or the other for change in the internal political system, like the Italian Red Brigade, the German Baader, the Shiites, the People’s Volunteer Force and the Boko-haram extremist group etc, each with their own agitations. All of which have used assassination and threats to frustrate national security.

According to Ogbaji (2012), terrorism has had some obvious negative effects in many countries of the world. The most common is that it diverts resources into internal security functions instead of diverting such into development projects. These resources are also used in protecting political leaders, guarding vital locations, screening people at the airports and all these required increasing amount, labour and time with serious implications on the national development. In other words, terrorism can simple be seen as the use of fear to coerce, persuade, and gain public attention through violence.

According to Laqueur (1999), there is no universal acceptable definition of the term ‘terrorism’ though United States Department of Defense (1990) described terrorism as the unlawful use of, or threatened use of force or violence against individual or property to coerce and intimidate governments or societies, often to achieve political, religious or ideological objective.

National Security

There are various views on the concept of security. The issue of national security is very important one to any nation, and this is because a nation’s state in terms of her peoples’ well-being economically, socially, politically, internationally and so on is greatly influenced by her standing in the matter of national security. The citizens, groups, institutions, corporate organizations and the country in its entirety are security conscious. It is in the nature of man to always try to safeguard his physical body, property and even his interests because he needs to do so in order to remain alive, be significant and also protect his acquisitions.

National Security according to Former U.S Secretary of Defence, Robert McNamara (1968) in his work “The Essence of Security’’, means “development’’. Security to him is not military hardware, though it may include it, security is not a military force, though it may involve it, security is not traditional military activity, though it may encompass it. He stress that security is development and without development, there cannot be security. As development progresses so also is security. When a nation-state organized their own human and natural resources to provide themselves with what they need and expect in life, and learned to compromise peace among competing demands on the large national interest, then their resistance to violence and disorder will largely increase.

Security is often treated as a common sense term that can be understood by “acknowledged consensus’’. The content of international security has expanded over the years. Today, it covers a variety of interconnected issues in the world that have an impact on survival. It ranges from the traditional or conventional modes of military power, the causes and consequences of war between states, economic strength, to ethnic, religious and ideological conflicts, trade and economic conflict, energy supplies, science and technology, food, as well as threats to human security and the stability of states from environmental degradation, infectious diseases, climate change and the activities of non-state actors.

National security connotes different meanings to different people. According to Makinda (1998), national security could be describe as the ability of a state to carter for the protection and defence of its citizenry; and this definition fit into the confine of national security.

However, over the last decades, the views about security has been extended to cope with the 21st Century global trend, its rapid technological developments and the global threats and challenges that embedded with the new trend. On such view, Al-Rodhan (2007) rightly propose that,

The “multi-sum security principle’’ which is based on the assumption that in a globalized world, security can no longer be thought of as a zero-sum game involving states alone. Global security, instead, has five dimensions that include human, environmental, national, transnational and transcultural security, and therefore, global security and the security of any state or culture cannot be achieved without good governance at all levels that guarantees security through justice for all individuals, states, and cultures (200).

In other words, these five dimensions have different divisions. The first is the human security, which deals with the principle object of the individual and not the state. United Nation Institute of Peace (2011) views human security as ‘‘the absence of threats to the vital interests of individual people on a worldwide basis”. The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in its 1994 Human Development Report originated the concept as an alternative to the traditional concept of National security. Human security is security as applied to people rather than territories. It includes freedom from pervasive threats to people’s rights, safety of lives, involving both, safety for people from violent threats, such as organized conflict, gross violations of human rights, terrorism and violent crime. The second dimension deals with the environmental security which includes environmental degradation, climate change, economic crisis, illicit drugs, infectious diseases, global warming and access to resources, that is to say, it deals with natural disaster. The third dimensional division is where the issue of national security comes in and it’s linked to state monopoly over use of force in a given territory which emphasises the military and policing of other component security.

In other words, these third division deals with defence and survival of the state from external aggressions or attack which is the Conventional Security approach. Transnational threats such as terrorism, crime, human trafficking etc. are the fourth dimensional and the fifth is the trans-cultural security which deals with that of integrity of diverse cultures and civilization in all forms. All these five security dimensions need to be address in order to provide a just conducive and sustainable atmosphere for security and peaceful co-existence between states and cooperative interaction among them will help to tighten up the security (United State Institute of Peace, 2011).

In the view of Kofi Annan, what constitute security threat in our contemporary world is any event or process that leads to deaths on a large scale or the lessening of life chances, and which undermines States as the basic of international system, should be viewed as a threat to International Peace and Security. According to Annan, these six clusters of threat includes; economic and social threat, including poverty and deadly infectious diseases, inter-State conflict and rivalry, Internal violence including civil war, State collapse and genocide, Nuclear, radiological, chemical and biological weapons, terrorism and transnational organized crime (The Economist, 2004).

More so, Onuoha (2008) equally maintain that security denotes the capacity of a state to promote the pursuit and actualization of the fundamental needs and vital interest of its citizens and societies, and to protect such from threats, which may be economical, social, environmental, political, military or epidemiological in nature.

In order to make a way forward in achieving a sustainable atmosphere for peace and security of the nation and globe at large, a well democratic governance and an articulated policy programme for human development will go a long way in addressing the insecurity problem the nation and the entire globe is facing today because a vibrant civil society and democratic governance is more imperative for security than an Army.

The Impact of Boko-Haram Terrorism on the Nigerian National Security

Nigeria’s national security has been affected on many fronts by Boko Haram terrorism in Nigeria since 2009. The terrorist group started innocuously as a benign religious organisation, but it quickly turned not only malignant but intractable, defying solutions. Since 2009, Boko Haram has carried out several awe-striking attacks in Nigeria, and most of the attacks elicited international outcry. For instance, the abduction of over 219 students of Government Girls’ Secondary School who were writing West African Examination Council (WAEC) test in the town of Chibok in Borno State, Nigeria, on the night of April 14, 2014. The rescue of the young female students since then is yet to be put to a logical conclusion. Some of the victims of the abduction were also feared to have been radicalised and married off to the Boko Haram members.

Similarly, on December 25, 2011, Boko Haram terrorist group under one of their leaders by name Abubakar Dikko (a.k.a Kabiru Sokoto) bombed St. Theresa‘s Catholic Church Madalla, Niger State, near Abuja. About 48 persons died in the attack while over 200 Christians were hospitalized. On Friday January 6, 2011, members of the sect struck in Mubi, Adamawa State and killed 20 Igbo men and women. At the end of such massacre this deadly group issued a three-day ultimatum to southerners mainly Christians to leave northern Nigeria. Some of the efforts made to track down these sects produced weak results (Newswatch, 2012, January 30).

These attacks among other things impacted negatively on the defense and survival (national security) of Nigeria given that it affected the economy, destabilized the polity, and terrorised the populace, as hereunder demonstrated.

Indeed, the activities of Boko Haram in Nigeria have retarded socio-economic development in various ramifications, and by extension, the Nigerian national security. According to Nkwede, Abah and Nwankwo (2015), these include;

- Food Scarcity: Prices of food in Nigeria now compete with that of gold due to food scarcity, no thanks to Boko Haram in Nigeria. This is because the traders from the Northern Nigeria are finding it extremely difficult to transport their commodities to other parts of the country. More so, the most farmers have been forced to leave their farmlands out of fear, and ran to safety in another part of the country where they live the life of mendicants instead of contributing to the food production in the country. This singular condition caused scarcity of food, and its attendant high price in the Nigerian markets, and it wields serious implication on food security in Nigeria.

- Irregular Migration and Abandonment of Profession: Boko Haram displaced most of the people of the North Eastern Nigeria. They left their homelands and places of habitual residence in the North East for their dear lives, to other safer parts of the country especially, to the South. It should be noted that it is not the Southerners alone that are migrating from the North but also the Northerners on account of insecurity. Most of these migrants from the North are in their productive age of farming and trading (Alao, Atere, Alao, 2015). The danger is that they have abandoned their profession which is largely farming and as argued above, has drastically reduced food production and distribution, and then, a serious problem to food security.

- Heightens Indigenes/Settlers Dichotomy: The activities of Boko Haram in Nigeria have forced the people of the affected area to leave their residences for the sake of safety, and it has heightened citizenship question which encourages hostility between indigenes and settlers. There were also the threat of crimes and criminalities associated with the migration not only against the host regions of the country but against the migrants who were more often than not, viewed with suspicion as members of Boko Haram that have come down South under the cover of Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs), just to perpetrate evils in the Southern Nigeria. This situation is a huge threat to human security in Nigeria.

- Discouragement of Local and Foreign Investment: As a matter of fact, the vicious onslaughts on individuals and institutions provides highly unfavourable business environment for local and foreign investors. Foreign investors contribute in no small measure in boosting the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of a country. Foreign investors create livelihood opportunities through the creation of job opportunities and the provision of large scale products and services in the host communities. The unfavourable business environment created by the violent activities of Boko Haram no longer avail Nigeria this opportunity. It is true that the Nigerian Gross Domestic Product (GDP) recorded appreciable growth to being the biggest in Africa but that does not negate the devastating effects of the terrorist attacks on the country’s economy. One great fact is that crisis is a serious threat to economic investments especially, foreign direct investments. No single investor makes an investment without checking the relationships between the opportunities and risks. Boko Haram terrorism blighted the attractiveness of Nigeria to foreign investors. At the height of the crisis, the United States of America warned their citizenry against travelling to Nigeria, not to talk of investing in the country. It is needless to say that a country is only as strong as its economy.

- Dehumanization of Women, Children and Men: Armed crises have serious implications against women, and children. The activities of Boko Haram in Nigeria reached a crescendo into the dehumanization of women, children and men especially in areas where rape, child abuse and overall human rights abuses. The attack and abduction of over 200 girls at Government Girls’ Secondary School, Chibok in Borno State, the attack on Federal Government Boarding School at Buni/Yadi, attack on ladies believed to be on mini-skirts in Maiduguri among others locus in quo. Human rights abuses abound, and at a point it assumed a bi-directional dimension where the terrorists were not the only the perpetrators of the abuses but also the forces involved in counter-terrorism. This is evident in a report by Amnesty International in 2015 which was titled: “Nigeria: Stars on their shoulders, Blood on their hands: War crimes committed by the Nigerian military”. The report accused the military brass of violation of the civil rights of the North Easterners all in the name of fighting Boko-Haram insurgency. What is more, violation of human rights implicates human security.

- Overall Deterioration of the Nation’s Economy: The overall effect of this insurgence on socio-economic development is that the economy is fast deteriorating. It has constituted the hallmark of socio-economic development. With the enormous resources at its disposal, leadership in Nigeria is confronted with the problem of focusing its expenditure priorities on security in disfavour of viable human capital development and other growth productivity promoting sectors (Ogege, 2013). Of course, it posed a serious challenge to a dynamic framework for the provision of job options.

The progresses of the existing investments are also affected by the Boko-Haram insurgency. For instance, commercial banks have been forced to review their operational hours to begin from 9.00am to 12.00 noon as against the normal operational period of 8.00 am to 4.00 pm (Mohammed, 2012). According to Mohammed, this is a part of efforts by these financial institutions to safeguard their business premises. By this operational arrangement, bank customers especially traders, had difficult depositing their daily proceeds in the banks due to the limited banking hours that are no longer in their favour.

- Overall Destabilization of the Social and Political Sectors: The 1999 Constitution of Nigeria as Amended unequivocally called Nigeria and indivisible and indissoluble entity which in whole or in parts cannot be controlled illegitimately. But then, the activities of the Boko Haram sect took control of a sizeable parts of Nigeria (such as Bama, Gwoza and Munguno), and declared it a Caliphate. This fact blighted Nigeria’s territoriality, and national security. The north and south of the country are in disharmony as a result of allegations and counter allegations against each other. There is established impression in the minds of the majority of the southerners that some northern leaders, disgruntled with the loss of leadership in the past nine years, have decided to precipitate crises using religious and sectarian platforms. According to the southerners, these frustrated leaders from the north have the belief that rulership of this country is their birthright. For instance, political power rested in the north for 38 years out of 50 years of this country’s existence (Obumneme, 2012). But having understood that the current political arrangement in the country has changed in contrast to their expectations, and having also realized that restoring the power (rulership) to status quo may not be easy, they decided to hide under the religious sect, Boko-Haram to express their ill-fated anger and ill-feelings. That is why they decided to incite the members of the sect and other people at the downtrodden from the same north, who were already aggrieved and frustrated following the high-handedness of the same leaders, who have been tormenting, alienating and denying them of their fundamental human rights.

Corruption, Inter-Security Agency Rivalries and the Failure of Counter-Terrorism in Nigeria since 2009

The counter-terrorism in Nigeria since 2009 has failed to yield a desired result. It baffled the Nigerian citizenry, political analysts and observers the apparent helplessness of the Nigerian government at the face of Boko Haram ravening rampages in Nigeria. Conspiracy theorists have even argued that the government was anything but sincere in the fight against terrorism. These crop of people insist that Boko Haram is fair and square, a political tool in the hands of the political movers and shakers in the country. While there may be some logical and believable indicators to this theory, there is clearly lack of evidence to showing that Boko Haram receives “official” sponsorship by the Nigeria government that has even suffered serious blows from its attacks. There might be insiders in the government who might want to achieve certain political of economic goals with Boko Haram, but possibility of official sponsorship of Boko Haram is entirely out of the picture. If not for any other reason, it is instructive to state that President Goodluck Jonathan lost his re-election bid in 2015 eminently on the spate of insecurity in Nigeria during his reign.

Furthermore, the administration of President Muhammadu Buhari is not finding it funny in the hands of Boko Haram terrorists since he took over the reins of the leadership of this country. As a matter of fact, his administration is fast loosing legitimacy due to its inability to tame the Boko Haram monster for greater national security in Nigeria. Be that as it may, the failure of the counter terrorism in Nigeria is attributable to corruption and inter-security agency rivalries in the implementation of the counter-terrorism strategies in Nigeria.

It is notable that despite massive expenditure and fat resource allocation by the Nigerian government over the past decade, counter-terrorism operations by security forces have achieved limited success and the country is still ranked on the Global Terrorism Index as one of the states most affected by terrorism. Chiefly, the corruption in the top military brass and other security agencies and institutions in Nigeria is the cause of the problem.

The situation has remained bleak and worrisome. It is estimated that terror groups have killed over 30,000 people in Nigeria since 2003, causing the displacement of more than 2.4 million people. These groups include Boko Haram, operating in the Lake Chad Basin region, Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP) and Ansaru, also called al-Qaeda in the Lands Beyond the Sahel. In a similar development in December 2019, ISWAP beheaded 11 Christian hostages to avenge the killing of Islamic State leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi by United States forces. In January, 2020, the group killed the chairman of the Adamawa State chapter of the Christian Association of Nigeria, Lawan Andimi. It also kidnapped three university lecturers in Yola in eastern Nigeria, and carried out several coordinated attacks in Borno State (Ogbonnaya, 2020). Most of these attacks came after the federal government led by President Muhammadu Buhari declared that Boko Haram has been “technically” defeated.

Meanwhile, Nigeria’s government allocated over N6.7 trillion to the security sector between 2010 and 2017 to strengthen its capacity for counter-terrorism operations. This amount doesn’t include extra budgetary allocations such as the US$1 billion the government borrowed in 2013 to fund counter-terrorism operations and the US$21 million approved for the Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF) in June 2015. Despite these increased money in form of fat allocations in foreign and local currencies for the security sector, counter-terrorism operations by the Nigerian military in collaboration with multilateral agencies such as the MNJTF of the Lake Chad Basin Commission have achieved limited success. The military did for a time succeed in pushing terrorist groups out of major cities, as was seen when the frequency of attacks in urban centres dropped between late 2015 and early 2018, but the resurgence of the Boko Haram terrorism like Phoenix from its ashes indicates serious flaws in the counter-terrorism.

Conflict entrepreneurs within the hierarchy of military leadership and the ministries, departments and agencies in the security sector apparently use military funds meant for counter-terrorism operations to enrich themselves. Military spending is usually not audited due to its sensitive nature. The secrecy that surrounds it encourages misappropriation (Ogbonnaya 2020):

Examples include the probe into the alleged diversion of US$2.1 billion meant for arms procurement by the Office of the National Security Adviser, and another N3.9 billion by the office of the Chief of Defence Staff, both in 2015. In 2017, US$43 million cash meant for covert operations by the National Intelligence Agency was discovered in a private building in Lagos. And in 2018 there were investigations into US$1 billion that went missing after being appropriated to the Nigerian Army for arms procurement from the Excess Crude Account.

There are also cases of fictitious procurement contracts awards and illegal extra-military activities such as extortion and collusion with militants in illegal fishing in the Lake Chad area. These lucre-inclinations of the military and other relevant agencies, ministries and departments of the Nigerian government in the counter-terrorism circles in Nigeria stifle and sub-ordinate the big picture which is the security of Nigeria. Yes, these activities undermine effective security force action by hollowing out the military’s capabilities. For instance, because they don’t procure by approval, and sometimes procurements aren’t even made, the military may be lacking in weapons and logistics, making it difficult to adequately counter terrorism.

This is evident in the reports from military sources which put the blame of the death of 83 soldiers in a 2016 Boko Haram ambush and a similar 2018 attack on the 157 Task Force Battalion in Metele, Borno State, on equipment shortfalls, poor weapons and logistics supplies, and low morale among combatant officers, who sometimes aren’t paid. Over 118 soldiers including the battalion commander died in the attack. In a number of reported cases, a number of soldiers drafted to fight Boko Haram at the battlefronts in the North East mutinied or deserted.

Way Forward

Terrorism will end when Nigerians see themselves as one people and develop that sense of community. In a short- to medium-term, Adibe (2014) argued that the government should adopt a combination of carrot and stick strategies such as:

i. Empowering the state governments in the north to lead the charge and be the faces of the fight against Boko Haram. This could make for ownership of the counter-terrorism and make it to look less as the invasion of the North by the infidels. This will also decentralize the counter-terrorism operations from the exclusive control of corrupt military officials and other security agencies.

ii. Creating a Ministry of Northern Affairs (just like the Ministry of Niger Delta Affairs): This ministry will help to address the numerous challenges in the North, including the problems of poverty, unemployment, illiteracy and radical Islam. This establishment would be one way of winning the hearts and minds of the locals and cooling local grievances on which Boko Haram feeds. The NACTEST of the federal government has been criticized among other things as lacking ministerial superintendence. However, the danger of creating this ministry is the possibility of creating another avenue for pilfering away the public largesse instead of using it for the noble intention of bettering the lots of the Northerners in Nigeria.

iii. Conducting speedy and fair trials, under Islamic laws, of those found to be Boko Haram activists or funders and letting the law have its full course. It is explicable that the intractability of the Boko Haram terrorism is largely due to the backing of the high and mighty within the governmental circles. There is crucial need of deploying intelligence techniques to unravelling the smokescreen perpetrators or sponsors of Boko Haram. Having the identifiable suspects stand for trial will send a strong signal to other marauding terrorists, and serve as deterrence to them. It may also be strategic to try the suspects under Islamic laws since the sect members have openly rejected Western civilization, including its jurisprudence. Whatever punishment is meted to them under Islamic jurisprudence will not be seen as part of Western conspiracy against Islam.

iv. Instituting a sort of Marshall Plan for the Northeast aimed at winning the hearts and minds of the local populace. The plan should aim at providing quality education, building local capacity and providing jobs.

v. Exploring the option of offering amnesty to the more moderate members of the sects while side-lining the hardliners and finding means to effectively degrade them. The instrumentality of amnesty as a conflict resolution mechanism was largely effective in the Niger-Delta region; such can also be replicated in addressing the problem of Boko Haram in Nigeria.

Conclusion

The dangers of Islamic fundamentalism on national security is definite and convincing and, regrettably, there is no quick fix to fighting terrorism anywhere in the world as the experiences in Afghanistan, Somalia, Yemen and other countries have shown.

One thing is clear: a security-only military approach to fighting terrorism not only precludes democratic culture and attitudes, but further radicalizes the religious terrorist group and strengthens the collective resolve of its members, who are unlikely to compromise (which means betraying their faith). A security-only approach also risks pushing yet more restless, jobless and frustrated northern youths into violent extremism and ‘negative identity’. According to Keller (1983: 274), ‘an overreliance on intimidatory techniques not only present the image of a state which is low in legitimacy and desperately struggling to survive, but also in the long run can do more to threaten state coherence than to aid it’. The corruption and inter-security agency feuds associated with military options do not help matters either. This research, therefore, concludes that an effective counterterrorism policy in Nigeria must go beyond an exclusively security-driven logic to embed counterterrorism in an overarching national security strategy that not only appreciates the ideological context in which (Islamist) radicalisation occurs, but also tackles poverty and the corruption-driven alienation felt by many in northern Nigeria. These factors contributed to Boko-Haram’s support and justification. If the counter-terrorism efforts against religious terrorism in northern Nigeria are to be effective, the Nigerian government must also invest in inter-religious dialogues between leaders of the two dominant religions in the country: Islam and Christianity. Such dialogues will help to clear cloud of misunderstanding and create a better atmosphere of mutual tolerance. Thus, a range of short- to medium-term strategies which are designed to address not the terrorism but its root causes can effectively resolve the crisis in Nigeria. The strategies can be pursued concurrently, and through the strategies, Boko-terrorism can be contained, degraded and eventually neutralized.

References

Abiodun, A. (2009) Islamic radicalization and violence in Nigeria https://www.securityanddevelopment. org/pdf/ESRC%20Nigeria%20Overview.pdf

Abugbilla, F, M, (2017) Boko-Haram and Africa Union Response. International Relation and Diplomacy. University of Arizona, Arizona USA.

Al-Rodhan, N.R.F. (2007) The Five Dimensions of Global security: Proposal for a Multi-sum security principle. LIT Retrieved from https://www.amazon.com/five-dimensions-global-security-multi-sum/dp/382580478X.academia.edu. >Nayef 6/1/2021 12:00am

Baffaello, P, & Sasha, J.(2015) From Boko-Haram toAnsaru. The evolution of Nigeria Jihad. Retrieved from www.rusi.org/publication. Occasional paper 23/11/2020

Easton, D. (1957). ‘An Approach to the Analysis of Political Systems’. World Politics, Vol. 9, No. 3.

Easton, David. (1965). A Systems Analysis of Political Life. New York: Wiley.

Laqueur, W. (1999) The new terrorism. Fanaticism and the Arms of Mass Destruction. New York: Oxford University Press

Makinda, S. (1998) Sovereignty and Global Security. https://journals.sagepub.com Retrieved on 14/9/2020

Ogbonnaya, M. (2020). Has counter-terrorism become a profitable business in Nigeria? Institute for Security Studies. Accessed from https://issafrica.org/iss-today/has-counter-terrorism-become-a-profitable-business-in-nigeria

Okeke, V.O.S. (2013) Beyond Diplomacy: Terrorism, Global Peace and Security. Nsukka: Great AP Express Publishers Ltd

Onuoha, G. (2006). Contextualizing the Proliferation of Small Arms and Light Weapons in Nigeria’s Niger Delta. Africa Security Review, 15(2).

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), 2018. Partnership with United Nations System Entities. Available at: https://www.unodc.org/unodc/ en/terrorism/ partnerships/CTC_CTED.html

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), 2018b. EU-Nigeria-UNODC-CTED Partnership Project III. Support for Criminal Justice Responses to Terrorism and Violent Extremism. Available at: https://www.unodc.org/brussels/en/eu- nigeria-unodc-cted-partnership-project-ii.html

Yusuf, H. (2007) Managing Muslim-Christian conflict in northern Nigeria: A case study of Kaduna State. Islam and Christian-Muslim Relations 18, no.2, April, 237-256

|

|