|

Maximum Vocal Art in Music Performance: Indispensability of Breathing and Breath Control

Lucy K. Onyekomelu

Department of Music, Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu University, Igbariam, Anambra State, Nigeria Email: luciyke485@gmail.com

Abstract

Good vocal art music performances that appeal to the ear and soothes the soul are the burning desires of every audience from its performers especially the erudite ones amongst them. The foundation of vocal art music lies in the proper control of the breath. Investigations and observations have shown that over fifty percent of music undergraduates in Nigerian tertiary institutions can hardly render a vocal art music performance without producing disjointed and broken notes or cracks and non-flow of the words they vocalize. Until a performer knows how to control the breath and unite tones, only then is he equipped to convey every variety of expression expected of him in vocal art music performance, else, the art of singing would become a chimera. By means of applying the working principles of the larynx and pharynx which are part of the respiratory mechanisms in the process of sound production, this paper will explore; the act of breathing and breath control in vocal art music, show reasons why impressive breath control in vocal performers should be developed and exercises for developing control of escaping air in vocal performance. All these will in turn ground the undergraduates in maximum vocal art music performance if imbibed in them early enough by music educators.

Keywords: soothes, erudite, disjointed, vocalize, chimera, imbibed

Introduction

Arts transcend science. Human beings marvel at the divine design of creation of the human voice in a scientific sense, but the special qualities that makes a person a good singer and the average person devoid of talent goes far beyond a desperate attempt to fit the artistic square peg into a scientific round hole (Holland, 2012). Moreover, the art of vocal sound production in music is a scientific process that beats the human eye. It is a natural phenomenon that involves breath which is life itself as seen in the words of Praise George (2006:14). If one’s breathing is right, then his/her singing will equally be right. Most ancient writers and teachers of vocal performance(s) placed a great deal of emphasis on the importance of studying breathing and breath control early on in the course of learning to sing. In line with the above, Graham Hewitt (1978) records that as long ago as the seventeenth century; the famous Italian teachers were known to have checked their pupils’ breathing, firmly believing that ‘he who breathes well, sings well’. Breathing is the single most important element in vocal art music performance because; the key to good vocal art performance is breathing properly and controlling the breath correctly. The difference between speaking and singing is the continuity of vibration and energy. In speech, energy is constantly arrested but it is never done in vocal music performance. When one breathes in, or inhales, he takes in air and when he breathes out or exhales, it is still air that is taken out. The ability of controlling these airs is what makes a vocal art performer unique, distinct and successful because, good breath makes a visible difference in the quality of the vocal sound produced by a singer during art performance.

Breathing properly has some positive effects ranging from calming the mind and the body to making it possible to support a good musical tone. The foundation of all vocal art studies for vocal art music performance should lie in breathing and the control of breath. Stressing this, Giovanni (1975) rightly states that:

The technical development of the voice is brought out by the double functioning of the lungs, which consists of: first, inhaling the breath noiselessly; and secondly, making use of the diaphragm to control the breath as economically as one pleases, in order to leave the vocal apparatus completely independent. (The diaphragm is a muscle on which the lungs rest and which is indispensable to singing) (5).

It is obviously clear from the above that, unless a vocal art performer becomes a master of the organs of breath, he cannot begin or succeed in the imperceptible merging of one tone into another during performance.

The Concept of Singing and Performance

Singing is an art, a complex sensory motor activity that requires finely co-ordinate interaction of the organs of aural perception, phonation, respiration and articulation which is monitored by the brain. Singing is expressing one’s innermost feelings in melody through words. This is because “man sings when he has something to express” (Nnamani 2002:78). It also involves emotional connection and the desire to communicate through music. Watson and Hixon (1987) describe singing as a “complex biomechanical process” (337). Bunch (1998) summarizes the complexity of singing by stating “simply put, the singing voice is a combination of mind, body, imagination and spirit, all of which work together – no one without the other” (p. 1).

Performance on the other hand simply means the act of doing something. According to Lexicon Webster Dictionary (1996), to perform means “to fulfill, carryout and accomplish an action and obligation” (746). Ekwueme (2012) defines performance as an act of doing or performing a task. It is, simply, to sing or play an instrument. Performance has connotations of musicians performing music before an audience. It is the ultimate goal towards which all efforts are geared and directed to in the world of music. This ultimate goal generally showcases common attributes in its capacity as a medium of communication (Ibekwe 2012). Okonkwo (2012) equally notes that performance is a medium through which a composer communicates certain ideas and feelings to a listener. Miller (1973) in support of performance being a communication medium also states that performance is trying to communicate an ideal sound which recreates the composer’s ideas as nearly as possible to an audience. Going further, he says that a carefully organized performance results in real communication. It is obvious from the above therefore; that there is always a message which every art performance sends across. This message(s) are usually sent by the performer. The vocal art performer has the task of interpreting and communicating a piece of music effectively to his audience. These he can only do, through the proper use of breath and its control which is the nucleus of vocal art music. Hanna (1977) goes further to say that musical performance invokes several means of communication such as motor, visual, auditory among others.

These means of communication can only be invoked if the vocal art performer knows in entirety how to unite his tones by controlling his breath in order to convey every variety of expression that is expected of him during performance.

Problem Statement

Great majority of vocal problems faced by vocal art music performers according to Holland (2012) results from confusion between the working principles of the passive and active divisions of the singing organisms. Explaining further; it resembles a novice driver who attempts to use the same pedal for the accelerator and the brakes. By pushing the pedal for increased speed, he simultaneously applies the brakes, releasing the brakes, he shuts off the vehicle. Investigations and observations have shown that most of the music students in our tertiary institutions today can hardly stand on their feet to render a good vocal music performance. They run away from such performances. As a result, a good number of them that have graduated from school often times find themselves in a state of confusion and crisis when it comes to vocal performances. They continue struggling to fit in and be accepted in the ever competitive performing environment they see themselves in, with little or no success. Those of them that dares to perform, struggle and mutter words during their performances thereby leading to production of disjointing and breaking notes, cracks and non-flow of the words that they vocalize.

This paper, by exploring the act of breathing and breath control in vocal art music performance, will show reasons why performers should developed impressive breath control; it will also show exercises for developing control of escaping air in vocal performance. All these will in turn ground the undergraduates in maximum vocal art music performances if imbibed in them early enough by music educators. Every singing begins with breath and all vocal sounds are created by vibrations in the larynx caused by air from the lungs. Breathing in everyday life is a subconscious bodily function which occurs naturally. However, the singer or performer must have control of the intake and exhalation of breath to achieve maximum results from his or her vocal performance. Vennard (1967) believes that proper breathing and breath control is central to an efficient vocal technique. Expressing further; “there are those teachers who consider breathing the most important factor in tone production…. Conversely, poor singing is directly the result of poor breathing, that consequently, there is just one thing to teach, correct inhalation and exhalation” (18).

The voice which is the object of vocal sound production is like a diamond in its unpolished state, i.e., when it is undeveloped. The beauty comes out and shines when skilled artisans work on it. People cannot really tell whether they can or cannot sing until they have involved and subjected their voices for training over a period of time. Investigations have shown that many who thought they could never sing always marvel at the pitch range they attain after fundamental and proper training by a vocal teacher. Breathing and breath control are the neglected aspect of vocal training that needs to be harnessed, and developed so as to bring the vocal performer’s voice to its maximum and optional functioning capacity during performances. They are basically, two indispensable sequels that should be inculcated in performers earlier on in the course of their training lessons as beginners. Seemingly driven by the above, Okonkwo (2013) asserts that “lessons on breath control should always be the singer’s first lessons as beginners. Good breathing makes for good sound production” (224). In the words of Adedeji (2000), it is a generally accepted fact that proper breath control is fundamental in singing.

Action of Breathing

To understand how to breathe, you must understand how the respiratory system works.

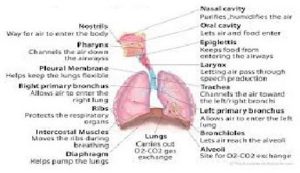

Fig. 1: Human Respiratory System

From Fig. 1 above, the diaphragm muscles surround the lungs. To breath in, the diaphragm lowers and expands into the regions of the stomach and intestines. It takes more energy to inhale than exhale. When you exhale, the job of the diaphragm is to resist completely deflating the lungs all at once. In vocal music performance, this action must be managed so that a steady flow of air can be put through the vocal instrument; that is the voice. The inhalation needs to be as full as possible and the exhalation needs to be slow and controlled. To accomplish this, the vocal performer needs good posture (sitting or standing) and control over the breathing process.

Natural breathing is an involuntary action, i.e. a person is not conscious of the action. Yet breathing can also be controlled by will as a person can make himself breathe faster or can stop breathing. This is a voluntary action. There are three stages in natural breathing: breathing-in period, breathing-out period, and a resting or recovery period. Within singing, there are four stages of breathing. These stages according to Godman & Gutteridge 1982 include:

- breathing-in period (inhalation)

- a setting up controls period (suspension)

- a controlled exhalation period (phonation) an

- a recovery period. These stages must be under conscious control until they become conditioned reflexes. A well-developed technique of controlled breathing in and out is invaluable for singers and marvelous for anyone’s general health. It expands the chest by an inch or two, flattens sagging tummy muscles and correct one’s posture.

It also cleanses the lungs, re-oxygenates the blood efficiently and relaxes one when he or she is nervous or tensed. There are three aspects of breathing which a performer or singer must acquire:

- the ability to inhale large quantities of air,

- the ability to snatch a good breath quickly, and more importantly,

- the ability to control the escape of breath.

Different Kinds of Breathing

There exist different kinds of breathing which according to Ameye (2009) includes:

Dramatic Breath: In music, there is the dramatic breath. In this case, the way you breathe is based on the expression or interpretational needs of the song. For example, you might take a louder, gasping type of breath to give an effect in a vocal performance at a moment of anger or disbelief. You might use a slow kind of breath to express tiredness or despair. Your use of air in the cases above is “expressive”.

Silent Breath: It is also important to know how to take a silent breath. In fact, you will use this kind of breathing most often when you sing (and when you record) in vocal performances. The breath comes in quickly through your mouth (and nose) and goes deep into your lungs with very little sound. Your ribcage is open and expands easily as the air pours in.

Relaxation Breathing: This involves helping to calm the singers’ minds; to prepare them for the concentration it takes to work quietly with focus on improving vocal technique.

The diaphragm plays a crucial role in breathing, in relation to vocal performance. This involuntary muscle called diaphragm is actually shaped like an upside-down bowl. It is attached to the bottom of the ribcage, and is the main muscle responsible for inhalation. When you breathe in, the diaphragm descends, creating a vacuum that sucks the air into your lungs. The abdominals are the primary muscles used for exhalation. When one exhales, the abdominals contract to bring the ribcage back inwards. This process pulls the diaphragm back up, expelling the air outwards.

The diaphragm and abdominals are both assisted in their processes by the movement of the intercostal muscles which are located between the ribs. As air fills the lungs, the ribcage naturally expands outward. This is only achieved through the expansion of the external intercostals. During the exhalation process, the ribcage returns inward, helped along by the internal intercostals.

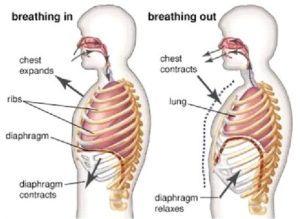

Fig. 2: Action of the diaphragm during the breathing process

In singing, the breath is regulated by how much the diaphragm is kept from moving up too quickly and by how much the vocal cord fold themselves in resisting the airflow. For any given pitch or dynamic, there is a range of optimal breath flow and breath control. When these two forces are balanced, a vocal artist performs very well. In proper singing, the diaphragm is not allowed to relax; rather it is kept active and buoyantly engaged. The vocal cords then regulate the remaining air stream. These mechanisms work simultaneously to make a pitch.

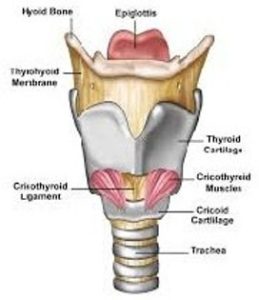

The voice that the vocal music performer uses to perform emanates as a result of the vibrations of the vocal cords which is dependent on the respiratory muscles. These vocal cords always adjust to be able to reach the pitch and dynamic requirements of every musical note sung during performance. The vocal art performer employs the working principles of the larynx and pharynx which are part of the respiratory mechanism in order to perform the co-ordinate activity of singing.

Learning to Breathe: Learning to breathe properly for the purpose of singing can be very demanding. To learn to breathe with an expanded and controlled breath; divide the breathing process into three parts: upper chest, middle chest (abdomen) and lower chest (waist). Each of these areas can be separately controlled. To identify these areas, lie down and put your hand on your chest. Place your thumb at your sternum (the place in the middle of your chest just below where the ribcage ends) and point the tip of your little finger toward your belly button. Your hand is now covering your middle chest area or the place where your abdominal muscles are located. Breathe in by expanding only the upper chest area. Next, practice expanding only the middle chest area. Finally, practice expanding only the lower chest area. The lower abdominal muscles in this area are the strongest and they normally contrast during sound production while singing. If the vocal art performer can learn to keep the chest expanded and held high and the rib cage open all the time, he will be assured of becoming a very great singer.

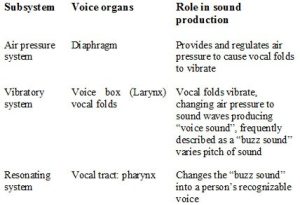

Table 1.0: The Voice Organs and their role in sound production

Fig. 3: The Larynx and Pharynx

Epigastria are also very important in singing. It is not a muscle but the point where the abdominal muscles and diaphragm meet. It is located in the upper abdomen (right under the ribcage), the epigastria forms “breath support” by engaging the abdominals and diaphragm at the same time, a consistent, supported flow of air is able to be expelled from the lungs. One can feel this muscle at work by taking a deep breath in and hissing out on a “ts” sound. The epigastria will tighten, allowing you to hiss out your air.

To sing better, a vocal performer must learn to preserve a reservoir of air in the lungs that supports and holds up small amount of air released across the vocal cords. The attractiveness of an art performer’s voice in making vocal music is what will make the listeners or audience stay till the end of the performance. Listening to an attractive voice perform is a highly rewarding stimulus which is usually obvious and striking thereby, motivating the listener to consume a startling amount of music. The vocal art performer must know how to unite pitch, rhythm and tempo in his performance because; these are the elements that will make his voice attractive. In order for the performer to unite these elements, he must learn to breathe properly and control the breath he has taken. The breath control should be a flexible process void of rigidity. It is the management and control of breath that makes a good performance.

Reasons for Developing Impressive Breath Control in Students/Performers

Breath control has to be developed for two reasons:

- Composers sometimes write long phrases of music for the performer to cope with, and unless the performer knows how to budget the outgoing supply of air, he is going to run out of it quickly and be forced to break a long phrase which should be sung in one breath.

- While singing a fairly long phrase, the pressure which forces the air to escape through the vocal cords must be sustained otherwise, the voice will sound as though the performer is running out of breath.

Exercises for Developing Control of Escaping Air in Vocal Performance

Hewitt (1978) outlined the following as exercises for developing control of escaping air in vocal performance. Stand relaxed and take a breath (from the bottom of your lungs, of course) the shoulders should be hanging lose as if you are carrying two buckets of water. Now expire on F or a low note, slowly, gradually and evenly, don’t collapse the chest even at the end of the breath, imagine you are expanding it, and this will ensure it stays high. It will pull on the abdominal muscles and hurt until you are used to it.

You must continue until you are exhausted, but towards the end, take another breath and repeat the exercise. If your stomach muscles are out of condition, you will find some difficulty in performing this exercise smoothly. Almost as soon as you start to sing a long phrase, the diaphragm should gradually, not suddenly, raise itself to give support underneath the lungs. This keeps constant the pressure of escaping air and must be continued until you have finished singing. By about the middle of the long phrase, you may feel that you are running out of breath, but you are not. There is plenty of air still in the lungs and you have to make use of those airs to give the voice a new lease of life.

The support given to the lungs by the upward movement of the diaphragm can be reinforced by pulling-in the abdominal muscles below the diaphragm. By doing so, you can guarantee a strong and steady vocal sound right up to the end of the longest phrase. This pulling-in of the abdomen also happens when you cough or blow up a balloon.

Get few balloons handy. A new balloon is stiff; you need a lot of puff and more pressure to stretch the rubber. Your cheeks are blown up, but nothing happens until you automatically pull in the muscles just below your waist. This extra ‘kick’ which the breath gets, produces enough pressure to inflate the balloon. This is exactly what happens when you are sustaining your singing.

“Messa di voce” – the Italian term for starting a note quietly and increasing its volume until it is loud, then gradually decreasing back to almost nothing is probably the most valuable of all breath control exercises. To practice it, choose a comfortable pitch in the middle of your range, sing OO, AH, a hum or anything you find easy, make the rise and fall in volume. Slowly and gradually, play with your voice, feel that you have control over it and repeat the process. Another exercise which will quickly show you how much air should be escaping is this: Sing in front of a lighted candle without making the flame flicker. Hold the candle about nine inches from your face, sing a phrase or an exercise easily and gently too with proper breath support and crescendo if you so desire. The flame should barely move. This is a very old exercise that is very valuable. It is now established that the most important aspect of good singing technique is breathing and control of air. Vocal art performers must control their breathing or they become fatigued quickly and the singing suffers. When all these are learned and applied properly, immediate result of improved and good performance is achieved.

Below are some pedagogical breathing exercises that will produce immediate result of improved performance(s) if practiced on a daily basis.

- Standing, with the fingers of both hands of the students/performers pressed into their sides at waist level, slowly and easily take a deep breath, concentrating on filling-up from the bottom of the lungs. (Students/performers, may find that breathing through the nose makes for a fuller, deeper breath and of course it warms and cleans the air, making it less harsh on the throat). Think of it as an extension of ordinary breathing: feel the air going down, deep into the bottom part of the lungs. If the students are doing it properly, their hands will be eased out. This is because, the lungs should expand downwards as well as sideways and in doing so, the muscles underneath are flattened and pushed outwards.

- The students should try lying on their backs to practice breathing exercises. When they are lying down, the breathing is deeper and they can easily feel the movement of their muscles.

- Let them hold a heavy object above their heads: using something heavy enough to make lifting it an effort – like a bucket of sand on a bar-bell. Their breathing should fall easily into the right place.

- Students should sit on a firm, straight – backed chair, hang their arms loosely and move the elbows away from the sides of their chest. Without moving the shoulders and with their backs touching the chair – back, they should take a long, slow, deep breath from the bottom of their lungs. They should try to expand so that their backs swell and presses against the chair. This particular exercise quickly establishes the sensation of waist and back expansion while breathing in.

Summary

Since “all arts evolve towards music” Erick More (1978:71), tenacious efforts should be made by music educators to imbibe in their students early enough the tenets of good singing. They should according to Ojukwu (2013) should teach for transfer.

The need for students to be grounded in the foundations of vocal music performances early on cannot be overemphasized. The vocal performance teacher has the responsibility of educating and training the performer as well as the listener and therefore must cultivate their perceptions (Bunch, 1982). Effective training is achieved through giving of instructions at intervals, participatory observation, imitation and rote teaching and learning from the teachers.

There must be underlying basic objectives as far as music teaching of vocal performance is concerned. The knowledge and performance of music should bring richer appreciation into the life of students and performers and help in developing their intelligence, competencies and appreciation. Seemingly driven by the above, music educators in vocal performances should teach their students how to:

- Breathe properly through the nose and mouth simultaneously with a resulting swelling of the muscles, without shrugging the shoulders so that the widest part of their lungs are filled with air.

- Control the breath so that the outflow is gradually utilized in producing a good vocal sound and

- Pulling in the abdominal muscles so that the shape of a champion lifter is obtained and the high notes are sustained without cracking.

Conclusion and Recommendation

This paper, having established that the tenets of good singing and maximum vocal art music performances lie in good breath and proper breath management recommends the following; that educators of music and voice teachers who are saddled with the responsibility of giving proper music education in the area of vocal performance(s) should be concerned with teaching their students the etiquettes of good vocal performance which is embedded in breathing and breath control in order to be able to face the competitive performing environment in which they are and the ever competitive environment which they will eventually find themselves once they graduate from school.

Not only that, since assertions have been made by experts that students/performers learn more about vocal performances by performing music and this is because when a piece of music is sung or played, various principles and systems are applied and learned at the same time than when the music is dormant on a piece of manuscript. The students and performers therefore should be subjected and encouraged into lots of practical music experience(s) which will help them to think conceptually and analytically about the functions of various musical elements and equally put them in practice as they sing and perform.

More so, university and college music educators in Nigeria have a challenge in the area of producing highly skilled singers and performers because, they are needed to satisfy our societal needs for good vocal performance techniques required in our country’s vocal production and performances. Going by the above therefore, music educators should teach their students the necessary skills and techniques required in vocal performance(s) early on, so that they would be grounded in the area and techniques of good vocal art music performance.

Above all, the performers on their own part should develop their singing talent through practice for practice makes perfect, and it also makes permanent. They must work hard in order to improve their singing ability, putting in practice what the educators taught them. A famous pianist once said “if I don’t rehearse for one day, I know; if I don’t rehearse for two days, my wife knows; and if I don’t rehearse for three days, my audience knows”. Nothing good and lasting comes to someone without discipline and hard work. The students’ vocal ability is not going to improve by chance, overnight or by a ‘miracle’. It will only improve by training and exposure. So, the key to achieving all these is practice, and when a performer knows how to control the breath and unite his tones through practice, only then will he be able to convey all manner of expression expected of him in vocal art music performance else, the art of singing would become a chimera.

References

Adedeji, F. (2000). Voice Training Manual. (Book 1) Lagos: Femad Music Co.

Ameye, J. (2009). Breathing – the Secret of Instant Calm. Retrieved from http:/exinearticles.com/expert/Joseph Ameye/222404.

Bunch, M.A. (1998). A Handbook of the Singing Voice. London: Meribeth Bunch.

Ekwueme, L.E. (2012). Performance Music Programme: A Suggested Approach for Effective Music Education for the JSS Level. Lagos: Lenaus Advertising and Publishing Ltd.

George, P. (2006). Successful singing. Lagos: Success World Limited Nigeria.

Giovanni, B.L. (1975). Vocal Wisdom. New York: Taplinger Publishing Company.

Godman, A. & Gutteridge, A.C (1982). A New Health Science for Africa. Singapore: Selector Printing Co Pte Ltd.

Hanna, J.L. (1977). To dance is Human. In J. Blacking (Ed.). The Anthropology of the Body. London: Academic Press, 214 – 216.

Hewitt, G. (1978). How to Sing. Britain: Elm Tree Books Ltd.

Holland, J.M. (2012) Singing Excellence and How to Achieve it. Xlibris Corporation.

Ibekwe, E.U. (2012, March). Cultural Perspective on Music Performance in Africa: Children’s Musical Activities in Igbo Culture as Paradigm. A Paper Presented at the 11th National Conference of Association of Nigeria Musicologists. UNN.

Miller, M.H. (1973). History of Music. Toronto: Fitz-henry and Whiteside Limited.

Nnamani, N. (2002). The Use of Local Instruments in Christian Liturgy. Interlink: A Journal of Research in Music 1, 77 – 87.

Ojukwu, E.V. (2013). Adequate Lesson Plan: A Prerequisite for Effective Teaching and Learning of Music Awka Journal of Research in Music and the Arts (AJRMA), 9, 159 – 173.

Okonkwo, V.N. (2012, August). An Appraisal of Performance Education in Music in Tertiary Institutions in Nigeria. A Paper Presented at the 11th National Conference of Association of Nigeria Musicologists. UNN.

Omibiyi, M.A. (1975). Training of Yoruba Traditional Musicians. In W. Abimbola (Ed.), Yoruba Oral Poetry, 877 – 925.

The New Lexicon Webster’s English Dictionary (1996). Danbury, C.T.U. SA: Lexicon Publications Inc.

Ugoo-Okonkwo, I.A. (2013). Relating Human Voice Anatomy to Singing and its Training as a Musical Instrument. Awka Journal of Research in Music and the Arts (AJRMA) 9, 215 – 225.

Vennard, W. (1967). Singing, the Mechanism and the Technique. New York Carl Fisher Inc

Watson, P.J. & Hixon, T.J. (1987). Respiratory Kinematic in Classical (Opera) Singers. In Hixon, T.J. & Collaborators (1987) Respiratory Function in Speech and Song. Boston: College – Hill Press.

|