|

Global Online Journal of Academic Research (GOJAR), Vol. 1, No. 1, November-December 2022. https://klamidas.com/gojar-v1n1-2022-01/ |

|||

|

Utilizing Beliefs, Values and Habits as Tools for Determining Personal Outcomes

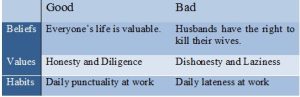

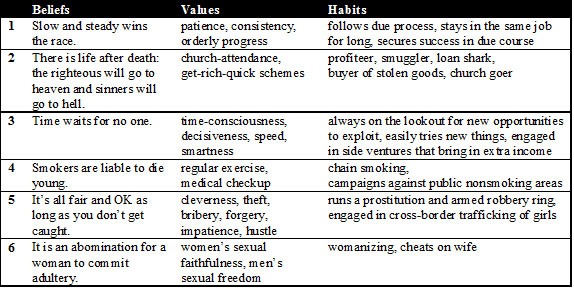

By Duve Nakolisa Abstract This paper identifies beliefs, values, and habits as the critical forces that dictate the outcome of an individual’s endeavours and their capacity to realize set goals. The paper presents and illustrates the view that the fundamental causes of success and failure lie in the beliefs, values and habits of the individual. It introduces new concepts and analytical tools invented not only to clarify the expository thrusts of the paper but to empower the individual to evaluate the direction of their beliefs, values and habits. Some of these new tools include the belief-values-habit (BVH) formulations and tables devised to enhance the individual’s ability to analyze and understand their own and other people’s behaviour and motives. The paper’s theoretical and practical insights are framed within the author’s BVH model and are presented as processes by which an individual can utilize beliefs, values and habits to determine the outcome of their undertaking. Keyword: belief, values, habit, BVH model, BVH tables, BVH codes, BVH sets, JBUT chart, success, personal outcomes Everyone’s beliefs, values and habits constitute the foundation of their success or failure in personal, occupational and social endeavours. Upon the fundamental tripod of beliefs, values and habits may be placed other factors which can boost or hinder an individual’s success. Some of these are vision, desire, focus, persistence, hard work, foresight, knowledge, creativity, and finance. But then, even these are products of an individual’s beliefs, values and habits. The puzzle is that there are people who fail to achieve appreciable success in spite of exhibiting all or most of the above qualities of successful people; there are, on the other hand, those who appear not to have some of these attributes but, regardless of that, end up attaining great success in their chosen careers. What could be the explanation for this incongruity or apparent disharmony between an individual’s apparent success attributes and the outcome of his or her endeavours? Concerning this, many perspectives and explanations abound. However, it is the position of this paper that there is an underlying relationship between an individual’s beliefs, values and habits and that person’s capacity to realize set goals. Some vital aspects of this relationship are explored in this paper. Beliefs, Values and Habits as Critical Outcome Fundamentals We need to define the terms “belief”, “values” and “habit” as a guide to our understanding of their fundamental roles in determining the outcome of an individual’s occupational/vocational endeavour or their capacity to realize set goals. Generally, a belief is anything an individual holds to be true and upon which they place some confidence. A belief is what someone recognizes, approves and accepts to be true with or without empirical evidence. Our beliefs differ because our personalities, upbringing, education, social exposure, culture, experience, and responses to all of these and other factors, differ. That is why someone may have the belief that they would succeed in achieving what they set out to do while another firmly believes that they would fail to realize their goal no matter how hard they try. To belief is to unleash a value chain, for it inevitably links one to values that make what one believes and its attainment possible or impossible. The above is a wide-ranging definition of belief; we shall adopt a functional or operative definition of the term, suitable for its measurable application, later in this paper. What are values? Values are the important ideas about key aspects of life an individual has formed over time, and usually from the standpoint of his or her beliefs. According to Schwartz (1992), values are “desirable states, objects, goals, or behaviours, transcending specific situations and applied as normative standards to judge and to choose among alternative modes of behaviour”. Elaborating on this point, Kaushal and Janjhua (2011) explain that values refer to the way in which people evaluate activities or outcomes and guide to a person’s intentions and actions… Values signify desired goals scaled according to importance, which guide a person’s life, behavior that is directed towards goals, and criteria for choosing those goals. Values are the standards by which an individual or a group of persons is guided to choose what to attain in life and by which they go through the process of attaining their goals. Some people confuse beliefs with values but they are two distinct terms. Pediaa (2016) distinguishes them as follows: Although values and beliefs are interrelated since they collectively affect our attitudes, perceptions, personality, character and behavior, there is a distinctive difference between them. The main difference between values and beliefs is that values are principles, ideals or standards of behavior while beliefs are convictions that we generally accept to be true. It is these ingrained beliefs that influence our values, attitudes, and behavior. Habits are the routine value-driven things an individual or a group of persons does to become who or what they are or to attain goals they set for themselves. Habits are the external expression of the internal beliefs and values of an individual or group of persons. Habits are someone’s regular behaviour; they are the acts they exhibit or undertake as they are propelled by their inward beliefs and values. There are good and bad habits. Good habits are the productive acts people regularly engage in that bring them good results. Bad habits are the unproductive acts they frequently engage in that bring them bad results. Generally, whether a habit is deemed good or bad is dependent upon what one believes and the values one holds dear. In visionary terms, a habit is considered good if it enhances one’s vision or goal and considered bad if it hinders it. An individual’s beliefs, values and habits can lead them to realize or fall short of realizing their set goals – depending on the type or nature of those beliefs, values and habits. So, while one belief-values-habit set can lead one person to success, another belief-values-habit set can lead another to failure. We will illustrate in a subsequent segment of this paper the critical need for people to choose or reinforce those beliefs, values and habits that steer them towards success rather than towards failure. We will also illustrate how beliefs, values and habits can be broadly classified and their impact practically determined as part of this papers purpose of exemplifying in what way or manner beliefs, values and habits can be utilized as tools for engineering success or the realization of set goals. Relationship between Workers’ Values and Workplace Performance It has been noted that there is a relationship between workers’ beliefs and values and how well they do (the habits they exhibit) in the work place (Elizur & Sagie, 1999). Most jobs make practical demands on workers – they demand their skill, their capacity to do something, to communicate and to deliver results. Kaushal and Janjhua (2011) are of the view that there is a relationship between personal values and performance in the workplace: Most of the early attempts in studying values have observed that values play a very important role in determining individual behaviour, decision making and managerial success… Moreover the similarity in value orientations…plays an important role in eliminating value conflicts and have significant implications for the organizations which need to integrate for high performance work systems in the organisations… The research on work values also conceived that work values are derived from people’s basic value systems that help them navigate through the multiple spheres of their lives… Dorkenoo et al (2015) also share the view that the values of workers have a direct bearing on their productivity since their attitude and performance of assigned tasks reflect their ingrained principles: Values can strongly influence employee conduct in the workplace. If an employee values honesty, hard work, and discipline, for example, he will likely make an effort to exhibit those traits in the workplace. This person may therefore be a more efficient employee and a more positive role model to others than an employee with opposite values. Values determine what individuals find important in their daily life and help to shape their behavior in each situation they encounter. Since values often strongly influence both attitude and behavior, they serve as a kind of personal compass for employee conduct in the workplace. Values help determine whether an employee is passionate about work and the workplace…. Beliefs, values, habits: these three are equally important. To believe the right things without valuing the right things can give one the conviction to go in the right direction but deny them the wisdom to make the right choices. To have the right values without cultivating the right habits can enable one to make the right choices but deprive them the capacity to take the right steps. Beliefs, values, and habits are inter-connected and this connection can be utilized by every individual to transform, intensify and speed up their capacity to become successful in whatever they choose to do. There is enormous power in the cumulative effect of these three forces, if one knows how to apply them methodically to break those barriers blocking them from realizing their goal or attaining self-fulfillment. Classifying Beliefs, Values and Habits Beliefs, values and habits can be broadly grouped into two classes: pro-success or positive beliefs, values and habits and anti-success or negative beliefs, values and habits. Positive and negative categorization is, incidentally, among some of the vital dualisms of life – in some ways as basic as good and evil, life and death, up and down, light and darkness. When beliefs, values and habits are positive, they vivify and instigate critical success factors such as purpose, vision, goal, passion, skill, diligence and integrity. When negative, they propel their failure-inclined captives towards laxity, purposelessness, aimlessness, apathy, laziness, shortsightedness, incompetence, feebleness, and dishonesty. It is the nature of the individual’s beliefs, values and habits that dictates the course of his or her life. It is what determines how people invest time, talent and other resources; how much they earn, retain and invest; and what determines the direction, quality and level of their overall personal and business development. More than A Matter of “Good” or “Bad” The average person can tell apart two extremely opposite beliefs, values or habits. On a moral scale, the bad attribute or act, because of its crudity, would weigh down the scale, lifting up the good attribute or act. Broadly speaking, and in spite of differences in culture or nurture, there is a natural capacity in every human being to distinguish what is obviously right from what is obviously wrong. So, the average individual can draw a table such as this (Table 1) without putting any data in the wrong column: Table 1

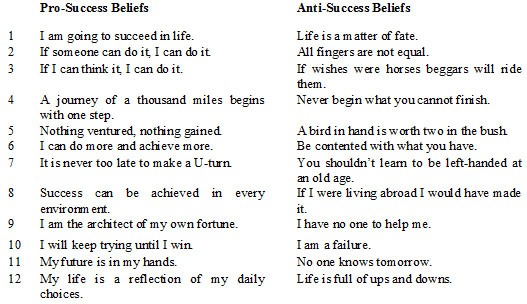

It should be noted, however, that in terms of their capacity to enhance or hinder success, all beliefs, values and habits do not weigh the same but the differences here are not necessarily distinguished by “good” or “bad” tags. In the terrain of success considerations, a seemingly “good” attribute, such as patience, can be rated low if, for instance, it has the tendency to detain a man on the same spot and make him to be doing the same thing and producing the same negative result year in, year out. And what about outspokenness? On its own, this is good, especially for an activist who needs it to articulate and communicate his or her cause. But this “good” habit will be “bad” if routinely exhibited by someone whose job demands or requires tact and sensitivity in addressing issues. This is why, for purposes of success evaluation, it is important to avoid the term “good” or “bad” in classifying beliefs, values and habits. Instead, they should be evaluated in terms of the positive (+) or negative (–) contribution they make towards the realization of a given vision or goal. Evaluating Beliefs as Drivers of Values and Habits Beliefs, in terms of the behaviours they spawn, can be broadly classified and labelled according to their tendency to enhance or hinder the capacity of those who believe them to accomplish their set goal. Hence, for the purpose of this discussion, we shall classify beliefs or statements of belief into two types: pro-success and anti-success beliefs. Pro-success beliefs or statements of belief are phrased in such a way that they express faith in the capacity or likelihood of those who believe or utter them to achieve success or cause a positive change in their lives. Anti-success beliefs or statements of belief do the opposite; they engender doubt, fear, complacency and failure. Table 2, using statements people commonly say or believe, exemplifies these two kinds of beliefs. The examples cited in this table are far from being exhaustive. Indeed, one could cite dozens of such everyday utterances if we had ample space for that. The ones we have listed here are meant to serve as a guide. The table should also make everyone more sensitive to the underlying meanings of regular statements people make. It should be realized that by those statements people, consciously or unconsciously, call up spiritual and physical forces that enhance the fulfillment of the tenor of their utterances, be it positive or negative. People should check themselves everyday to ensure that what they say is not an unconscious contradiction of what they want. Table 2: Pro-Success and Anti-Success Statements of Belief

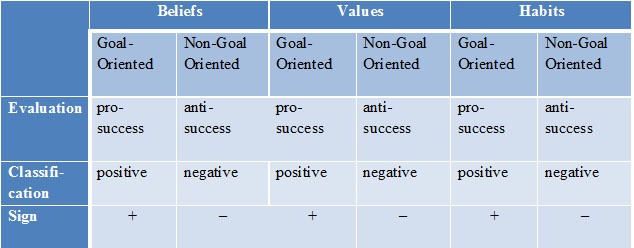

One may ask, why is one set of the above statements tagged “pro-success” while the other set is tagged “anti-success”? The difference is in the inclination of the speaker and believer of each statement to act according to the leaning of his or her statement. Speakers of the pro-success statements are usually more inclined towards taking steps to get positive outcomes than speakers of the anti-success statements who typically tilt towards resignation, apathy, and procrastination. This indicates that speakers of the pro-success statements are more likely to expect or take steps to get positive results than speakers of the anti-success statements. The latter are usually negative-minded and liable to doing little or nothing to change their situation. Pro-Success and Anti-Success Beliefs as True Beliefs Given the aforesaid fundamental difference between pro-success and anti-success statements of belief, can we then say that pro-success statements are true beliefs while anti-success statements are false beliefs? We need to derive or adopt a functional definition of belief before we would be able to answer this question. From a pragmatic point of view, a belief is defined by the predisposition of the one who believes to act according to what he or she believes. That belief is false if the believer acts or is disposed to act contrary to what he or she supposedly believes. A true statement of belief is that which inspires the one who believes it to act in accordance with its dictates. So, a statement is said to be a true belief if the one who utters or believes it is inclined to do or act in accordance with what it says; a statement is amounts to a false belief if the one who utters or purports to believe it is disinclined to do or act in accordance with what that statement says. In other words, a belief – in terms of what it means to an individual – is not in and of itself true or false but is either true or false strictly on the basis of what the one who claims to believe it is inclined or disinclined to do. It is the doing part that tells us whether someone truly believes something or not. Every individual tends to act in line with what they believe; so, we can gain a good insight into what someone believes by how they act. Alexander Bain was probably the first modern philosopher to recognize this connection between belief and action, a significant nexus as far as our discussion of the subject of belief, in this book, is concerned. Bain, in 1859, defined belief as “that upon which a man is prepared to act”. Max Fisch in Engel (2019) logically expressed it thus: “X believes p” means “X is prepared to act on p” Bain clarifies the relationship between belief and action thus: It will be readily admitted that the state of mind called belief is, in many cases, a concomittant of our activity. But I mean to go farther than this, and to affirm that belief has no meaning except in reference to our actions; the essence, or import of it is such as to place it under the region of the will. Bain in Misak (2016) went further to note the role of feeling as a binding force between belief and action: “The difference between mere conceiving or imagining, with or without strong feeling, and belief, is acting, or being prepared to act, when the occasion arises.” Given this functional definition of belief, can we say, referring to the question earlier posed, that the pro-success statements listed in Table 2.1 are true beliefs while the anti-success statements are false beliefs? Although the speakers of the pro-success statements are more likely to get positive results than the speakers of the anti-success statements, both categories of speakers are prepared or inclined to act in accordance with their utterances. So, both sets of statements are true beliefs: the pro-success believers are prepared or inclined to act positively; the anti-success believers are prepared or inclined to act negatively. In as much as the speakers of these two sets of statements have the disposition to act in accordance with the tenor of their statements, their utterances equally constitute true belief. The major difference is that one set of true beliefs is pro-success while the other set of true beliefs is anti-success. But pro-success beliefs and anti-success beliefs, being true beliefs, have the potential to influence the mind to make each believer act in accordance with what they believe. BVH Evaluation and Classification What we can call Belief-Values-Habit Evaluation, or simply BVH Evaluation, is a method devised by this author for assessing how success-oriented one’s beliefs, values and habits are. It is a result-oriented technique which, when mastered, can be readily applied. Early in life, most people were influenced to acquire certain beliefs, values and habits they now consider counter-productive. Such negative beliefs, values and habits should be done away with. It is the responsibility of the goal-setter or success-seeker to enforce necessary mental and behavioural changes to enhance the smooth realization of set goals. The BVH Evaluation is a soul-searching assessment of beliefs, values and habits based on their actual, potential or perceived relevance or irrelevance to the realization of one’s vision or goal. A belief or set of beliefs, values or habits is pro-success if it enhances or moves your vision or goal forward; it is anti-success if it hinders your goal or turns you partially or completely away from it. If someone’s belief, values or habit is evaluated as being pro-success, it is classified and noted as positive (+) belief, values or habit; if evaluated as being anti-success, it is classified and noted as a negative (–) belief, values or habit. This categorical assessment makes no room for neutral (0) or unsigned beliefs, values and habits. (See Table 3) Table 3: BVH Evaluation and Classification

The goal of the BVH Evaluation is to help every individual identify and categorize every issue of immediate or remote implication for their success journey. This evaluation will help them identify the success or failure orientation of their beliefs, values and habits through sorting them into two distinct categories: those which would enhance success vs. those which would hinder success. Many people should be able to do this, although how well it is done would significantly vary from person to person. Outcomes are Not Accidental Results To restate our position, everyone’s ability or lack thereof to realize set goals springs primarily from the tenor of their beliefs and values and the actions they propel him to take. These are what determine the outcome the individual obtains from any endeavour to which they channel their time, energy and money. Personal outcomes are usually reflections of what the individual inputted into their life in the areas of beliefs, values and habits. Outcomes are not accidental results. They are chains of interconnected forces that are difficult to deal with except one is conscious of and ready to make necessary adjustments regarding the leanings of their beliefs, values and habits. Figure 1: Pairs of Opposite Values and Outcomes

Every individual’s success or goal-chasing journey is in stages and there are not one but many outcomes. Every outcome expected at the end of every stage of the journey should be clearly and recognizably identified. This is the only way one can know whether they are making progress or not and whether one should reassess their beliefs, values and habits. Such reassessments should be used to make one better at attaining a set goal, not better at derailing it. A set goal or vision is the nucleus around which every idea or experience should revolve. Success is all about outcomes and outcomes are rarely accidental results. Outcomes spring from the soil of the individual’s positive/negative beliefs, germinate as their positive/negative values, branch out through their positive/negative habits to become their positive/negative results. See Figure 1 for an illustration of this vital relationship with particular emphasis on the connection between values and outcomes. In Figure 1, two sets of beliefs – positive and negative – are involved. Although these beliefs are not stated, you can use the ones listed in Table 2 as examples of positive and negative beliefs. In Fig. 1, a set of positive beliefs produced a set of positive values, namely, integrity, persistence, diligence, skill, passion, vision, and purpose. This set of positive values produced desirable outcomes, such as success, wealth, self-fulfillment, social assets, increased options, and increased influence. The negative beliefs gave rise to the following negative values: dishonesty, feebleness, laziness, incompetence, apathy, shortsightedness and aimlessness. These values, as illustrated, led to unpleasant outcomes: failure, lack, self-pity, social liability, decreased lifestyle options, and decreased influence. All of these are the opposite of the positive outcomes listed above. No right-thinking person would like these negative outcomes but, like them or not, they inevitably result when one’s beliefs, values and habits are continually anti-success. It seems reasonable to state that life usually delivers what we somehow allowed our beliefs, values, and habits to attract. BVH Interactions In this section of the paper, we will explore aspects of beliefs, values and habits in order to gain greater insight into their interactions and their involvement in shaping human behaviour. So far, we have seen the interaction between these three forces as a rather one-way chain, with beliefs leading to values, and values leading to habits, and habits leading to success or failure. While this sequential framework is not all there is to beliefs, values and habits, it rightly highlights the causative order of their interactions in ideal situations. However, when manifesting in the life of the individual, beliefs, values and habits can act in diverse ways. Personal-growth Gear Let us use the concept of what this paper calls personal-growth gear to describe the manner in which an individual’s beliefs, values and habits work together to enhance their personal growth and development. An individual’s personal-growth gear refers to the way their beliefs, values and habits move each other to generate capacity, efficiency, and productivity or incapacity, inefficiency, and non-productivity. Ineffective deployment of the personal-growth gear reduces the level of output, competence, and income an individual can produce. Incompetent engagement of the personal-growth gear is one of the fundamental reasons some individuals have failed repeatedly at whatever they tried to do. How effectively the personal-growth gear is put to use determines an individual’s success power. Each time someone thinks, each time they take action, they are engaging their beliefs-values-habits gear, projecting it to move in a certain direction and at a certain speed. (Note that by habits we include habits of gathering, sifting and analyzing information as well as habits of acting on the information.) Figure 2: Personal-growth gear

Every act is not a linear expression that necessarily springs from beliefs to values and, then, to habits. While, in formative terms, beliefs, values and habits unfold in a sequential way, they do not necessarily manifest that way; many times, they act simultaneously, like the parts of a gear, to change the pace or direction of someone’s beliefs, values or habits. (See Figure 2) What this means is that the success-seeker must continually be sensitive to the inter-relationship between these three critical forces (beliefs, values and habits) in order to ensure that none of them is out of alignment with set goals, since they produce best results when they are in alignment with each other. To believe one thing and do another is a clear indication that one’s personal-growth gear is not properly aligned. To return to the authentic path of growth and development, a realignment of BVH forces in a manner that powers one towards the desired direction would be necessary. When someone’s beliefs, values and habits are in agreement with each other, they can all be efficiently expressed in a single act through their gear-like interaction. The personal-growth gear, in enabling us to see in one instance of behaviour an individual’s essence, plays a synthetic and generative role. For example, someone casting his vote during an election is displaying belief in democracy while at the same time expressing an aspect of his democratic values and demonstrating a habitual inclination to participate in choosing his leaders. BVH Unit A BVH unit is made up of three components – belief(s), values and habit(s) – that form an identifiable meaning in a sequential or non-sequential manner. A meaning is sequentially obtained from a BVH unit when it is derived through a logical sequence of belief(s), values and habit(s). A BVH unit that forms a sequential meaning is called a BVH set. A meaning is non-sequentially obtained from a BVH unit when it does not emanate from a logical sequence of belief(s), values and habit(s). A BVH unit that forms a non-sequential meaning is called a BVH mix. The term “BVH mix”, as used in this paper, takes a singular or plural verb, depending on whether it is referring to a single BVH mix or two or more BVH mix. A BVH unit (be it a BVH set or a BVH mix) is susceptible to personal, social and environmental influences, among other factors capable of causing shifts in personal beliefs, values and habits over a short or long period of time. Those who withstand unsavoury influences to maintain behavioural stability achieved the feat by largely conducting their lives in line with the dictates of veritable BVH sets. Classification of BVH Units As we earlier stated, there are positive (pro-success) beliefs, values and habits and negative (anti-success) beliefs, values and habits. Units of beliefs, values and habits (BVH units) are also classified. There are three types of BVH units:

The first two types apply to BVH sets while the last applies to BVH mix. BVH units are usually distinguished in terms of the following features:

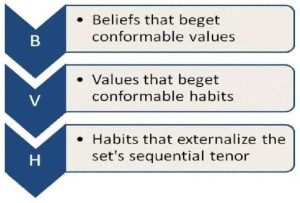

By type, we refer to the three BVH types (positive BVH units, negative BVH units, and positive and negative BVH units) listed above. The term, “tenor” is the general meaning or perspective a BVH unit is conveying or tends to be conveying. It is a feature of all BVH units. “Sequence” refers to the way the tenor or meaning of a BVH unit is derived: does it flow logically and conformably from beliefs, through values to habits or is it derived as a result of a contradiction in one or more BVH components? BVH Set A BVH set is a BVH unit whose meaning is derived through a logical sequence of belief(s), values and habit(s) that are in line with each other. What this means is that it is the conformability of the components of a BVH unit that determines whether it is a BVH set or a BVH mix. Because the components of a BVH set correspond to each other, the elements in the components being mutually consistent, they lead to a predictable pattern of behaviour. The contradictory components of a BVH mix, on the other hand, lead to unpredictable pattern of behaviour. A BVH set is either positive or negative in type. To determine what type a BVH set is, we ask the question: Are the beliefs, values and habits of this BVH set positive (pro-success) or negative (anti-success)? It is vital to note that the word, “success”, as used in the above brackets, is defined as the realization of a worthy goal or desire. If the goal of a given BVH set is evil, socially or morally harmful, the BVH set is deemed to be negative in spite of the “success” of its outcome. In this matter, the end does not justify the means. In any authentic success story, the value or glory of the outcome should be gauged by the integrity of the process. One of the defining features of a BVH set is that its belief(s), values and habit(s) point toward the same meaning or idea, thereby laying the foundation for its logical sequence. Thus, in a BVH set, the beliefs are in agreement with the values which, in turn, lead to agreeable habits that externalize the tenor of the set. (See Fig. 3) Figure 3: Logical sequence of BVH Set

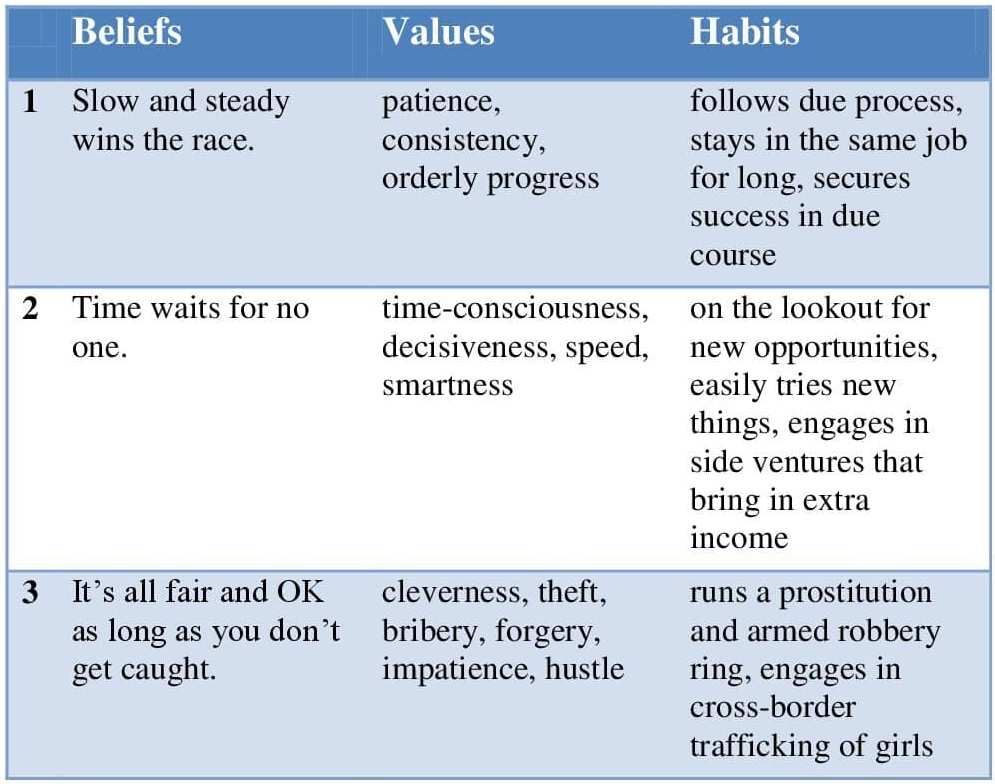

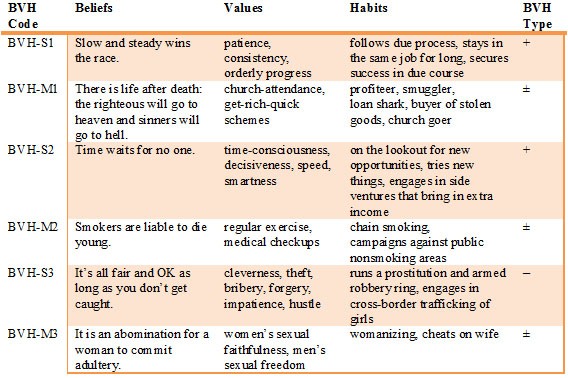

BVH Table A BVH table is a columnar presentation of BVH units that displays in the respective columns the belief(s), values and habit(s) of each row (or BVH unit) of the table. When a row of a BVH table displays belief(s), values, and habit(s) that agreeably link to each other, that row is called a BVH set. A row whose belief(s), values, and habit(s) are not altogether consistent is called a BVH mix. The BVH table below contains three BVH sets. Notice that each set’s beliefs, values and habits point toward the same meaning. Since conformable values and habits can correspond to conformable beliefs in various ways, BVH tables, such as the one below, may not contain exhaustive list of sets of possible beliefs, values and habits. To illustrate the topic, only three BVH sets are listed. Table 4: BVH Table

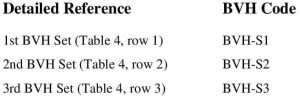

The above BVH sets are logically sequenced. Logical sequence is unique to BVH sets and refers to the order in which BVH beliefs generate conformable values which, in turn, give rise to conformable habits. We see this principle at work in the above BVH table where the values and habits of each BVH set flow from and build upon the conformable elements of the set’s belief component. BVH Codes BVH codes are ways of using letters and numbers to make convenient, simplified and orderly references to the BVH sets and BVH mix in a given table. BVH codes are derived from BVH tables for the purpose of uniquely identifying and analyzing BVH sets and BVH mix. Table 4 (above) is made up of three BVH sets which can be identified, as follows, in terms of their positions as rows of that table: 1st BVH Set (Table 4, row 1) 2nd BVH Set (Table 4, row 2) 3rd BVH Set (Table 4, row 3) Instead of referring to these BVH sets using the above lengthy forms, BVH codes can be used to sort and systematize such references as follows:

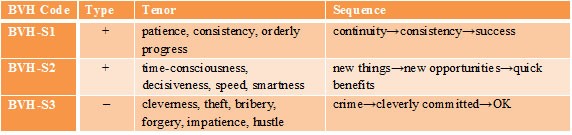

Note that the letter “S”, attached to the number identifying the row where the BVH set is located in the table, stands for “set”; it is used to distinguish a BVH-Set code from a BVH-Mix code. BVH codes can function as primary keys in BVH-Set and BVH-Mix tables as well as in database records. BVH-Set Tables A BVH-Set table provides quick tabular insight into the type, tenor and sequence of coded BVH sets. It is different from a BVH table whose columns merely indicate the beliefs, values and habits of a BVH unit (be that unit a BVH set or mix). BVH-Set table and BVH-Mix table have four columns each, namely, BVH Code, BVH Type (Type), BVH Tenor (Tenor) and BVH Sequence (Sequence). A right arrow (→) is used to show the logical sequence of a BVH-Set. The BVH-Set table below (Table 5) is drawn using BVH data provided in Table 4 above and the BVH codes derived from it. Table 5: BVH-Set Table

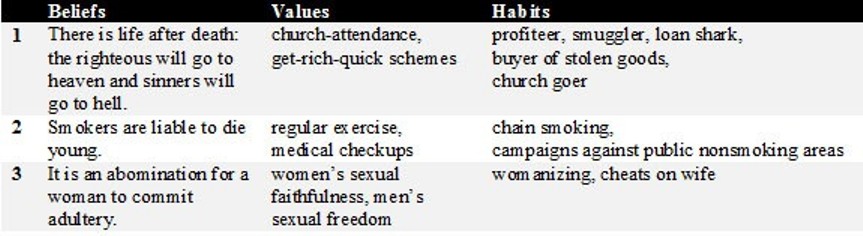

Note that BVH-Set table and BVH-Mix tables are not meant to serve as alternatives to BVH tables without which none of their columns will make referential sense. BVH codes symbolize BVH sets while BVH-Set and BVH-Mix tables provide useful information that makes more meaningful BVH tables. BVH Mix A BVH mix is a unit of beliefs, values, and habits that are not sequentially linked. A BVH mix, unlike a BVH set, is positive and negative in type, does not form a logical sequence from beliefs, through values, to habits, and so derives its tenor from inconsistent BVH components. The tenor of a BVH mix has two contradictory aspects: positive (pro-success) and negative (anti-success). Recognizing this two-part tenor is vital as it enables us to make useful distinctions while sorting out the sequence of a BVH mix. Under the “Sequence” column, a BVH mix’s tenor is prefixed with “pro-“ or “anti-“. These prefixes are attached to a word or phrase that captures an element of BVH mix’s contradictory tenor. If that element supports life, for example, we may refer to it as “pro-life”; and if it is against the use of vaccines, we may tag it “anti-vaccines” in the BVH mix “Sequence” column. The use of these two prefixes reflects the inconsistent pattern we see in a BVH mix and the illogical nature of its sequence. A forward slash is used to demarcate the elements of a BVH mix tenor. Example: pro-life / anti-vaccines. The BVH table below contains only BVH mix. Table 6: BVH Table (2)

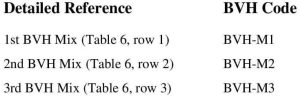

You will observe that each mix of beliefs, values and habits cannot be said to be logical or sequential as there is no mutually consistent meaning, as we see in a BVH set. This is why a BVH mix is not simply positive (+) or negative (–) but both positive and negative (±). In spite of its sequential discrepancy, a BVH mix is very valuable. It communicates information that reflects human foibles and the ironic nature of reality. There is so much inconsistency in real-life behaviour, so much disconnect between what people believe or claim to believe and what they actually do: this is what the BVH mix captures and expresses. Very few people lead lives that only BVH sets can truly reflect; in this sense, BVH mix may serve as a truer mirror of the average person’s behaviour. BVH Mix Codes Earlier, two distinct BVH codes – BVH set code and BVH mix code – were identified. While their functions are the same, BVH mix codes are distinguished from BVH set codes by the letter “M” (stands for “mix”) that precedes the number denoting the row where the BVH mix is located in a table. We can use BVH codes to represent each of the three BVH mix of Table 6 as follows: Table 7: BVH Mix Codes

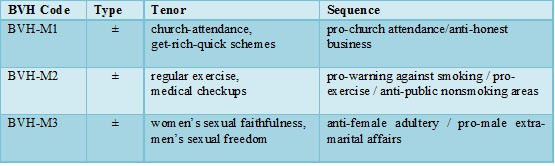

BVH-Mix Tables A BVH-Mix table provides quick tabular insight into the types, tenor and sequence of coded BVH mix. In spite of the fact that there is no sequentially-derived tenor and no logical sequence in a BVH-Mix table, it has four columns, the same number of columns we see in a BVH-Set table. This columnar uniformity enables us to combine both tables in a BVH-Set/Mix Table. The BVH-Mix table below is drawn using BVH data provided in Tables 6 and 7. Notice that the tenor of each BVH-mix is both positive and negative. Table 8: BVH-Mix Table

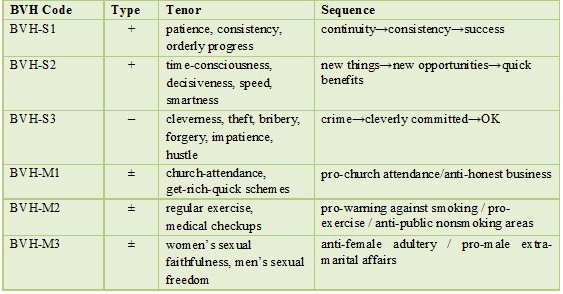

BVH-Set/Mix Table As earlier noted, a BVH-Set table can be combined with a BVH-Mix table to form a single table known as BVH-Set/Mix Table. Though a BVH-Set/Mix table is often a combination of BVH-Set and BVH-Mix tables, it can be a direct result of a single BVH table that contains rows of BVH sets as well as those of BVH mix. The BVH-Set/Mix table below (Table 9) is a combination of tables 5 (BVH-Set) and 8 (BVH-Mix). Table 9: BVH-Set/Mix Table

Assuming the data used in drawing the conclusions represented in this table were obtained from two or more BVH-Set and BVH-Mix tables, using a single BVH-Set/Mix table to represent it would give a more unified and comparative picture. The accommodation of such all-inclusive data is one of the benefits of a BVH-Set/Mix table. More on BVH Tables In this segment, we would show further ways in which BVH tables as well as BVH-Set and BVH-Mix tables can be presented. So far in this paper, we have drawn mostly separate BVH sets and BVH mix tables, and have combined them merely for illustrative purposes. However, a single table can contain, in interchanging pattern, units of BVH sets and those of BVH mix. In Table 10, we have alternated BVH set with BVH mix by joining two of the tables earlier discussed (Tables 4 and 6) to show how such a single table might look. Table 10

Table 10 does not present ready information on the type and nature of the six BVH units contained in the table. Additional information can be added by inserting BVH Codes and BVH Types to the table to give us what we can term a Joint BVH Units Table (JBUT). We can add BVH codes and types to Table 10 to turn it into a JBUT chart (Table 11): Table 11: Joint BVH Units Table (JBUT)

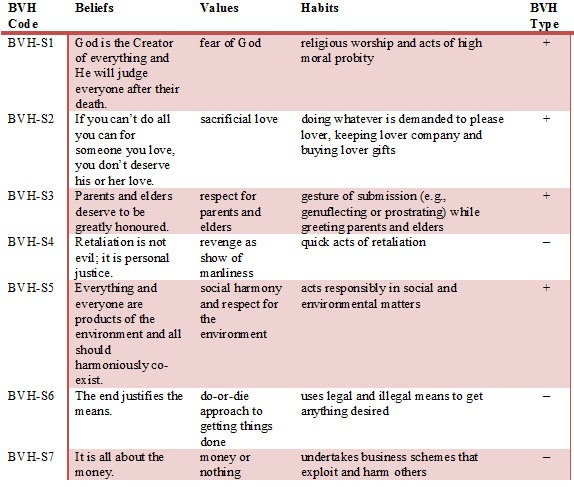

A JBUT chart contains five columns. The first is the BVH Code. The next are Beliefs, Values and Habits columns respectively. The fifth column indicates the BVH Type of each BVH unit. This is indicated with the plus (+), minus (–), or plus-minus (±) sign. A JBUT chart offers unique advantages. It gives all the information ordinarily obtained from BVH tables in addition to all the information, apart from the ones in the Sequence column, provided in BVH-Set, BVH-Mix, or BVH-Set/Mix tables. A JBUT chart results when BVH-code and BVH-type columns are added to a BVH table. On a final note, in describing the associated habits of a BVH set or a BVH mix, one should endeavour to state only the bare facts without qualifying them with judgmental adjectives or adverbs. Avoid labels that appear subjective and raise unnecessary questions: instead of writing, for instance, “silly drunkard”, simply write “drunkard” as there is no room in a typical table for you to tell us how silly the drunkard you have in mind is. In any case, tables of this nature may not typify only one individual; it may represent other drunkards all of whom may not be silly. BVH Relationships BVH Relationships refer to the way Belief-Values-Habit units or their components connect to produce patterns of behaviour. Given the awesome power of beliefs, values and habits as decisive factors in everyone’s personal growth and development, success or failure, we need to gain a little understanding of certain ways in which BVH units, their components or elements, can interact to yield positive or negative results. Such interactions between BVH units generate peculiar BVH relationships that, when understood, can enable the individual to strategize for success as well as enhance his or her understanding of the motives behind certain behaviours. Ordinarily, beliefs, values and habits of the same orientation work together. This is the ideal picture. So, when we see a person who believes that honesty is the best policy, who values integrity, we may conclude that he cannot take bribe to facilitate an illegal outcome. Conversely, when we see someone railing and fighting in public, particularly when he is beating a weaker person, it is easy to presume that he is a very rude fellow who has no control over his emotions and who, perhaps, believes that might is right. We usually expect someone’s beliefs to be in alignment with their values and habits. In reality, this is not always the case. Although more BVH relationships can be identified, we will discuss only three common ones, utilizing data from the JBUT chart below. The chart contains seven rows of BVH sets. The BVH sets are varied enough to represent some regular models of behaviour. Table 12: JBUT chart of some regular BVH sets

We can use the above chart and the two narrations below to identify and classify the following Belief-Values-Habit relationships:

Understanding these BVH relationships will be of practical benefit to us in our personal and business involvements. Below, we explore the above three Belief-Values-Habit relationships one by one. a. BVH Relationship of Correspondence You might have noticed that in each row of Table 12 every stated belief corresponds to the related values and habit. Of course, these are not the only values or habits these given beliefs could match. The important thing to note here is that the stated belief (denoted by the letter “b”) corresponds to the stated values (denoted by the letter “v”) which correspond to the stated habit (denoted by the letter “h”). This is why this kind of BVH relationship is called BVH relationship of correspondence. Because “b” is equal by definition to “v” (the kind of values denoted by “v” are correlatively equal to the kind of beliefs represented by “b”) and “v” is equal by definition to “h”, we can, using mathematical shorthand, represent this relationship of correspondence as: b ≙ v and v ≙ h. A relationship of correspondence is the prototype of the sequentially patterned behaviour. The regularity and predictability of this BVH relationship model is unmatched by any other BVH unit. b. BVH Relationship of Inducement BVH relationship of inducement results when an individual finds objectionable one of the constituent elements of a BVH set but is compelled to act in conformity with it due to the influence of an agreeable element extracted from another BVH set. This is not an uncommon relationship in human interactions as the following narration will show. 1st Narration: Glen was a young man from Europe who visited an African country for the first time. He lived for one month in one of the country’s major cities. During his short stay, he met and fell in love with a beautiful girl called Kemi. The two lovers were in some ways compatible but their cultural backgrounds were different. Glen’s cultural values were very liberal. He called his father by his first name, greeted him and other elders in his community without any special gesture of respect. Kemi’s ethnic setting demanded demonstrative respect for elders. Because they were obsessed with each other, Glen and Kemi never bothered to discuss cultural or personal differences. Before Glen travelled back to Europe, they had agreed to get married. When he got to his country, Glen discussed the matter with his parents and was delighted when they gave him their consent. What remained was for him to meet Kemi’s parents who were staying in the village, far from the city where he had met and interacted with their daughter. Shortly after receiving his parents’ blessings, Glen flew back to Kemi’s country to meet her parents. On the day he went, for the first time, to see his potential father-in-law and mother-in-law, he was accompanied by his fiancée and a few city folks, mainly young men and women from Kemi’s ethnic group. No one had prepared his mind about what to expect in his fiancée’s village home. On meeting Kemi’s parents, Glen’s gorgeously dressed entourage prostrated on the somewhat dusty floor. Although it was the first time the young foreigner was seeing such a behavioural display, he quickly recovered from his culture shock and also prostrated on the ground, almost synchronizing with everyone else. He waited till the last male member of the entourage stood up from the ground before he, too, did so. Kemi’s parents were impressed and Glen and their daughter were formally engaged. This foreign son-in-law kept up this habit of prostrating before his wife’s parents even after he had gotten married to their daughter. There is a BVH relationship of inducement in this narration and we shall use the above JBUT chart (Table 12) to illustrate it. Thenceforth, it is to this JBUT chart that all references to BVH codes or sets would be directed. Glen and Kemi share everything outlined in BVH-S2. Both of them in principle agree with BVH-S3, even though, because they never discussed it, Glen had no prior knowledge of the specific habit (a common cultural practice in Kemi’s ethnic background) outlined in BVH-S3, column 3. Both believe in honouring parents, and treating them with respect is part of their shared values; but they had no mutual understanding that this should be done as outlined in BVH-S3, column 3. This matter was never discussed before Glen found himself prostrating, for the first time in his life, before two strangers. What made him to do it? He believed in honouring elders, he valued respecting them but the related culture-specific habit of prostrating before them was very strange to him. So, what made him to prostrate? An interventional element from another BVH set – Glen’s habitual inclination to do “whatever is demanded to please (his) lover” (BVH-S2, column 3) – induced him to prostrate on the somewhat dusty floor as dictated by the objectionable element in BVH-S3, column 3. To make this concept clearer, let’s represent what happened with symbols. Two BVH sets are involved in this interaction. Set A consists of the following: BVH-S2’s Belief component (b2), Values component (v2) and Habit component (h2). Set B consists of the following: BVH-S3’s Belief component (b3), Values component (v3) and Habit component (h3). (Please revisit the table to see the comma-separated elements in these components.) These two BVH sets can be represented thus: A = {b2, v2, h2} B = {b3, v3, h3} Glen, we have earlier said, was in agreement with all the components of set A and all but one component (h3) of set B. Suddenly faced with the challenge of acting in accordance with this somewhat objectionable component (h3), Glen responded quickly by extracting an element (“Doing whatever is demanded to please lover”) from set A’s habit component (h2). This element induced him to comply with the objectionable demands of set B’s habit component (h3), thus creating, symbolically speaking, a new set which we may represent as follows: C = {b3, v3, h3, h2} To continue with our set imagery, we can say that this was how Glen’s initial misgivings were overwhelmed: compelled by the emergent set C’s combination of elements, especially by the powerful effect of h2, the influential element extracted from set A, Glen came to grips with the reality of the situation and quickly prostrated on the floor. When mastered and deliberately applied, BVH relationship of inducement can be a very useful self-improvement strategy. Now, you may ask, can the BVH relationship of inducement be used to account for Glen’s habit of prostrating before Kemi’s parents years after being married to their daughter? No. On that first visit, Glen prostrated on the bare ground in fulfillment of a perceived need to please his lover, not her parents. Subsequent prostrations (which, by the way, had become a low bow with only his right fingers touching the ground) occurred as a result of acculturation and in demonstration of his sincere respect for two amiable elders who loved him and took him as their own son. c. BVH Relationship of Concealment BVH relationship of concealment occurs when all the components of a genuine BVH set are concealed by the components of another BVH set. The latter BVH set is usually appropriated to deceive, confuse or oblige others. The appropriated BVH set can be said to be counterfeit because it is not the genuine BVH set of the appropriator. We shall use the following narration to illustrate BVH relationship of concealment. 2nd Narration: Georgio, convicted of murder and sentenced to life imprisonment, waited impatiently to be set free so that he could exact revenge on the man who was a key witness during his trial. He joined one of the religious fellowships in the prison and put up an outward show of piety. Because of his apparent good behaviour, he was released on parole. After his release, he reported regularly to the authorities in fulfillment of the conditions attached to his parole. Judging from his speech and social habits, the paroled prisoner appeared to be a man who had acquired some constructive values. People acknowledged his new religious belief, and the accompanying positive changes in his character. Georgio, from all appearances, seemed reasonably reformed and everyone considered him a changed man. They were wrong! The paroled prisoner’s genuine beliefs, values, and habits had not changed! He was only a good actor patiently waiting for an opportunity to strike. Barely two months after his conditional release, Georgio murdered the man who had witnessed against him during his trial and disappeared from town. The BVH relationship of concealment occurs when there is a masking of a set of authentic BVH components (let’s call it set A) by a set of inauthentic, often opposite, BVH components (set B). We can use the JBUT chart (Table 12) to explain the two key sets of behavior in the 2nd Narration. In that narration, a counterfeit set (set B) of beliefs (b1), values (v1) and habits (h1) (see BVH-S1) were deployed by Georgio to conceal his genuine set (set A) of negative beliefs (b4), values (v4) and habits (h4) (see BVH-S4). The genuine, though negative, BVH set can be represented thus: A = {b4, v4, h4} while the counterfeit, though positive, BVH set can be represented as B = {b1, v1, h1} Note that no element of set A belongs to set B as both sets share nothing in common. Because the two BVH sets are disjoint, we can express their relationship thus: A ∩ B = ϕ In BVH relationship of concealment, two disjointed BVH sets, one of which is authentic, are involved. To achieve manipulative or deceptive purposes, the authentic BVH set is concealed while the inauthentic BVH set is fronted by the manipulator. In the above narration, Georgio, the manipulative actor, concealed his authentic BVH set (set A) by covering it with his inauthentic BVH set (set B), thereby deceiving people and securing his parole. After that, he reverted to his authentic BVH set (set A) and executed his murderous retaliation against the man who had witnessed against him. The BVH relationship of concealment comes into play when someone feels the need to camouflage his or her true motives or values. It is commonly employed by the trust-breaching criminal who uses it to create a false image, win the undeserved confidence of others, and make his or her target victims less suspicious or vigilant. Those who may not necessarily be ill-motivated also employ this stratagem. For relationship reasons, and usually under the undue influence of peers, many people have employed this scheme to conceal their true beliefs or values when they perceive these to be contrary to the pervasive ethic of their social circle. What we get from this is that human beings can display patterns of behaviour that appear to affirm a given belief while, in reality, that belief may or may not conform to their genuine belief-values-habit set. Someone’s behaviour can indicate traits that do not, in any way, correspond to his or her genuine BVH set. All these make inter-personal relationships complex, with uneasy implications for personal development and visionary pursuit. One of the first steps some people need to take to discover and live their authentic lives is to identify and tear off the layers of BVH concealment which for years had complicated their development and hindered their success. We all need to remove all pretences and be true to that genuine voice and impulse in each of us directing us to our individual path of purpose and self-fulfillment. We need to be authentic to maximize our true worth, for authenticity is at the root of every durable success. Conclusion We have explored, in this paper, the pivotal role of beliefs, values and habits in determining the outcome of personal endeavours. And we have stressed that the inability of some people to achieve hilltop success basically springs from their failure to evaluate themselves, jettison negative mindsets and behaviours, and adopt and stick to only those beliefs, values and habits that steer them towards their desired goal. A lot of people are struggling with their careers, businesses and life goals – they are failing to be motivated by really great motivational stuff because they are yet to acknowledge and activate the success power that could be generated from their conscious refinement and deployment of their beliefs, values and habits. The ultimate point of this paper is that having control over the circumstances of life is significantly dependent upon how individuals evaluate, realign and utilize their beliefs, values and habits. References Bain, Alexander. (2016). The Emotions and the Will. https://archive.org/details/bub _gb_6DQCAAAAQAAJ. Dorkenoo, C. B., Nyarko, I. K., Semordey, E. Y. & Agbemava, E. (2015). The Concept of Workplace Values and Its Effects on Employee Performance and Corporate Profitability. Asian Academic Research Journal of Social Sciences & Humanities, Vol. 2(6), 288. Elizur, D. & Sagie, A. (1999). Facets of Personal Values: A Structural Analysis of Life and Work Values. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 1999, 48 (1), 74. Engel, P. (2019). Belief as a Disposition to Act: Variations on a Pragmatist Theme”. SemanticScholar.org. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/fd92/28fe6b8921f3ddf67b47203c95218bc7d515.pdf Assessed on 12th Dec., 2019. https://pediaa.com/difference-between-values-and-beliefs/. Assessed on December 9, 2021. Kaushal, S.L & Janjhua, Y. (2011, July). An Empirical Study on Relationship between Personal Values and Performance Values. Himachal Pradesh University Journal. Misak, C. J. (2016). Cambridge Pragmatism: From Peirce and James to Ramsey and Wittgenstein. Oxford University Press, 19. Schwartz, S.H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: Theory and empirical tests in 20 countries. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Zanna, M., Ed., Volume 25, Academic Press, 1–65.

|

|||