Jointly published by The Division of General Studies, Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu University, Nigeria (formerly Anambra State University) and Klamidas.com Journal of Education, Humanities, Management and Social Sciences (JEHMSS), Vol. 2, No. 5, November 2024. https://klamidas.com/jehmss-v2n5-2024-04/ |

||||||||||||||

|

Symbolic Characterisation in Nigerian Folk Narratives Bukar Usman

Abstract Folk narrative characters make sense to the local audience of folktale narrators primarily because of the social and symbolic values attached to the characters by the indigenous communities whose culture and cosmology gave birth to the tales. Unlike a modern short story, where the events of the story mainly determine how the character is viewed, the folktale utilizes the label placed on each given character by the culture to develop the conflict and unfold the theme or themes of the tale. This researcher undertook a study of one thousand (1000) folktales of Nigeria with a view to classifying them based on how the characters are socially valued and symbolised by their local audiences. The research was necessitated by the fact that the classification classes adopted by the well-known AT and ATU systems were found to be functionally inadequate when applied to folktales emanating from non-Western traditions, including Nigerian folk narrative traditions. Although there are other ways of classifying Nigerian folktales, this study undertook a classification of Nigerian folktales based on their character types. The result is an 8-character type classification of 1000 tales of Nigeria published in the voluminous book, People, Animals, Spirits and Objects: 1000 Folk Stories of Nigeria. This academic paper, adapted from my introductory notes to the book, sheds light on the symbolic values of Nigerian folk characters and why they can inspire a taxonomic distribution of Nigerian folktales. Keywords: characterisation, symbols, social values, Nigerian folk narratives

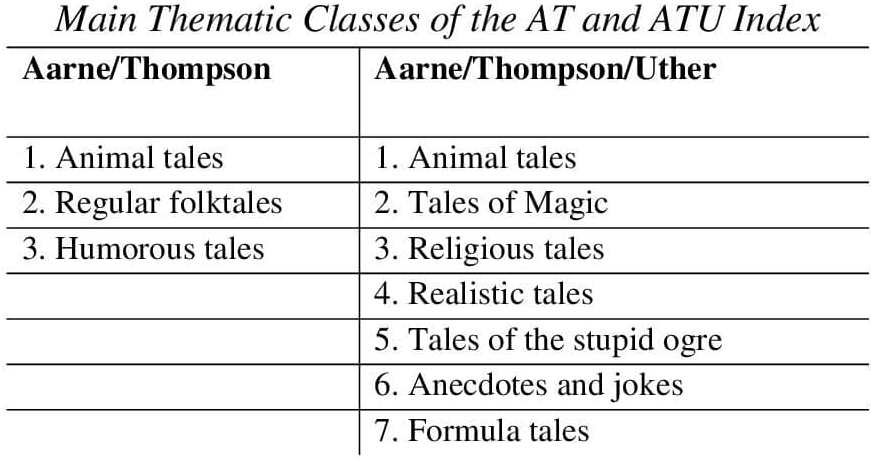

Introduction This exposition will briefly discuss two complementary topics. The first is the social values associated with folkloric tales while the second is symbolic characterization, a literary device which, in the arena of fictional tales, is socially mediated. One of the most enduring qualities of folktales is their social relevance. Folktales convey and stabilize social values such as respect for constituted authority, respect for spiritual ordinances, hard work, good neighbourliness, honesty, patience, courage, moderation, and love for one’s family and kindred. The need to preserve stories that propagate these social values was one of the reasons the Dr Bukar Usman Foundation conducted the Pan-Nigerian tale-collection projects which generated the tales of the Treasury of Nigerian Tales series. People, Animals, Spirits and Objects: 1000 Folk Stories of Nigeria is one of the books published under the series. All the folktales I will be referring to in this paper are taken from this collection. Social Values in Folktales Folktales are vital aspects of any nation’s folklore and this fact is clearly acknowledged by Emmanuel Obiechina, one of Nigeria’s pioneer literary critics. In the informed view of Obiechina (27), folklore embodies the values and attitudes (of a people) in its proverbs and fossilised saying, its belief in myths and religion, and its consciousness of its historical life, collective outlook and ethics, in its legends, folktales and other forms of oral literature. Concuring with Obiechina, the literary scholar, Saradashree Choudhury (3-11), says: “The folklore in traditional African societies has a highly educative value. It imparts knowledge on the groups’ history, values of warfare, morals, wise sayings etc”. In many areas of the world, the tale is the vehicle by which these communally-generated attributes are communicated and entrenched in the consciousness of the people. In Nigeria and other parts of Africa where, despite the fast-fading trend, it is still orally narrated to family groups, the folktale reflects the social pulse of the common folk. Carroll-McQuillan (1993) elaborates on this pulse: The African oral tradition embodies this pulse in an especially inclusive and expressive way. Stories in Africa weave music, audience participation, chants and choruses, even dance, into their fabric. Storytelling in Africa is an integral part of the culture. It is a common and effective means of teaching, preserving values and historical events, entertaining and is also an essential aspect of most ceremonial rituals. There is something about stories that make them appealing across all cultures, but folktales have a distinct rural flavour which makes them so fascinating. People love stories, especially stories that reflect their everyday realities; and sometimes the more removed the stories are from the common features of the immediate environment, the more charming they seem. This is one of the reasons many of us, rural- and city-dwellers, are initially attracted to folktales. Reading or listening to the stories gives us concrete benefits that urge us to explore further. Carroll-McQuillan (1993) explains: When we explore folk stories, we explore ourselves and our many facets as human beings. We see the reflection of humankind: its strength, flaws, fears, and hopes. The settings and characters may change but the heart and soul feelings are always there. They are timeless; they are ageless…in folk stories, we encounter a mirror in which we can see who we are and what we have been. It is a mirror charged with echoes of the past and hints of the future. Characters as Social Mirrors Writers and narrators mirror the realities of their environment through the various aspects of their story, namely theme, setting, plot and characters. But no matter how profound the theme of a narrative, how exotic its setting, and how excellent its language, it cannot succeed in delivering a competent story without a character or group of characters. Characters energize stories; they awaken and sustain our interest in the plot. Indeed, a story’s plot cannot unravel without characters. Those actions or inactions which make reading fiction worth it all happen around the characters in the story. A story moves from one episode to another because of the activities of its characters. The way in which an oral narrator or a writer portrays his fictional characters, and this is very important, is known as characterisation. Bernardo clarifies: What does characterization do for a story? In a nutshell, it allows us to empathize with the protagonist and secondary characters, and thus feel that what is happening to these people in the story is vicariously happening to us; and it also gives us a sense of verisimilitude, or the semblance of living reality…In the best of stories, it is actually characterization that moves the story along, because a compelling character in a difficult situation creates his or her own plot. A story’s characters interest us because we see our society, if not ourselves or those we know, through them. Characters are social mirrors. No matter the theme or orientation of a narrative – be that narrative a modern story or a folktale – the characters play the role of reflectors through which we see the variegated experiences of life. A character’s success in achieving this role depends on a number of factors most of which we need not dwell on here. But suffice it to note that the type of characters deployed by the storyteller is very crucial. While a major character in a modern short story tends to be round and generally realistically portrayed, the typical character we encounter in folktales tends to be flat in the sense of having one kind of personality trait. It should be stated that this apparent lack of complexity is compensated for by the stimulating symbolic nature of many folktale characters. Symbolic Relevance of Folktale Characters Although they are not endowed with complex traits, many characters we meet in folktales are significant and entertaining because of their attributes as symbolic characters. A symbolic character is one who reflects or represents an idea or concrete reality. Narrowed to folktale characters, this symbolic representation is invariably socially determined, thus ensuring that such characters personify culturally-fixed concepts, virtue or vice. The symbolic nature of its characters is a major reason a folktale is set in a familiar world of people, animals, spirits or objects and why its characters are drawn from this easily recognizable terrain. For this reason, as well, folktales are characterized by formulaic plots and traditional motifs. All of these make the folktale a communally-delivered art form. Symbolic attribution enables the narrator’s audience (or the reader of a written folktale) to get inside the head of a character and predict what the next move is likely to be. Depending on the narrator’s manipulation of the plot, during a story-telling session, or introduction of some elements of surprise, such predictions may turn out to be true or false. The symbolic attributes of the characters are outside the prerogative of the folktale narrator. They are socially determined over several generations and involve a “sociopsychological” process which is outside the manipulative powers of the narrator. In this process, according to J.L. Fischer, at least three semi-independent systems are involved: (1) the tale itself, considered as connected and rather tightly structured discourse; (2) the modal personality of the typical audience-narrator group for the tale; and (3) the social system relevant to the tale, including not only that segment of the society in which are found the active and passive participants in the tale (i.e., the “bearers” of the tale as an item of culture) but the pattern of the whole society. In the tale-bearing environment, this connection is easily established since the concerns expressed in folktales are usually the concerns of the common folk whose worldview is shaped by the collective consciousness of the community. It is this communal consciousness that had, over time, attributed symbolic meanings to the folktale’s typical characters. Thus, symbolic characters, in folktales, are cultural in origin and make customary sense because they spring from the age-old “memory” of a given ethnic or linguistic group. This description of cultural symbols by Carl Jung (93) is very definitive: The cultural symbols…are those that have been used to express eternal truths…They have gone through many transformations and even a long process of more or less conscious development, and have thus become collective images accepted by civilized societies. Such cultural symbols nevertheless retain much of their original numinosity or spell. One is aware that they can evoke a deep emotional response in some individuals…They are important constituents of our mental make-up and vital forces in the building up of human society…. Cultural symbols in the context of folktales function within a given social system which may be limited to a community or ethnic group or encompass many ethnic, linguistic or social groups. The relevance of these symbols, however, may be expanded, through migration and some other form of social integration, to wider social settings. Infact, due to cultural affinities among Nigerian ethnic groups and the prevalence of similar traditional motifs across folktales collected from different parts of the country, many stories of this collection have similar cultural symbols. A good number of characters the reader would be encountering through the 1000 tales featured in this book are symbolic. It is, therefore, important to briefly examine the subject of cultural symbols as they relate to characters featured in Nigerian folktales. Symbolic Characterisation in Nigerian Folktales Symbolic characterisation is the use of characters as symbols. This is a device employed in all fictional narratives, oral or written. In the case of folktales, including Nigerian folktales, the symbolic value of the characters are culturally derived. In modern short stories, the symbolic relevance of a character usually rests on the character’s engagements within the story. Unlike what obtains in the folktale, a character is not normally labeled outside the context of the contemporary short story. This is an important distinction worth exemplifying. Two short stories from Through Laughter and Tears: Modern Nigerian Short Stories can be used to illustrate this point. In Helon Habila’s “The Embrace of the Snake,” Lamang, the heartless manipulator of peasants from his own community, is the symbol of oppression whereas in Wale Okediran’s “Just One Trip,” Grace, the drug courier who swallowed a wrap of cocaine now tearing her health apart, is a symbol of foolhardiness. Both symbolic meanings are achieved purely by the actions of the characters within the stories, and not by any external cultural attribution. In a folktale, on the other hand, a typical character’s symbolic meaning is ascribed by the tale-bearing culture. This culturally determined label or symbolic value is so strong that presumptively the characters are portrayed in the tale in the manner dictated by the narrator-audience culture. For example, the hyena, in the stories where it featured in this book, symbolizes awkwardness, greed and foolhardiness. These are the qualities attributed to it by the story-bearing cultures of northern Nigeria and this informs the narrator’s portrayal of the hyena in any tale. This stereotypical characterization of the hyena delights the audience who has been culturally raised to expect the display of these symbolic qualities from the hyena. A few examples of stories (published in Usman’s People, Animals, Spirits and Objects: 1000 Folk Stories of Nigeria) featuring the hyena include “The Rabbit, the Tortoise and the Hyena” (No. 241), where the rabbit and the tortoise kill the hyena; “The Hyena’s Offsprings and the Rabbit” (No. 253), where the rabbit fool the hyena and malnourish its offsprings; and “The Hyena and the Ant” (No. 278), where the hyena is almost drowned by the ant’s schemes; and “The Wasp and the Hyena” (No. 303), where the wasp trick the hyena to drink itself to death. Some other instances are “The Hyena and the Spider” (No. 352), where the spider defeats the hyena in a wrestling match; “The Hyena’s Desire to Fly” (No. 436), where the hyena, on a monkey’s mischievous advice, tries to fly from a tree top but crashes down and dies; and “The Boy, His Pets and the Hyena” (No. 649), where the hyena steals food, is killed and eaten by other animals. In all of these scenarios, the hyena was discomfited or destroyed by physically inferior opponents. The hyena’s self-destructive miscalculations above delight the audience of each of these stories because this character’s behaviour in each instance matched its symbolic mould. Should the hyena behave contrary to its cultural tag, as in “The Hyena’s Dawadawa” (No. 606) where the hyena displays uncharacteristic patience, the story would seem unreal and the symbol-guided audience would most likely find it uninteresting. Can any group of Nigerian youngsters believe or appreciate a folktale where the tortoise, the nationally acclaimed trickster, is portrayed as honest, faithful, truthful, reliable, or selfless? Not likely. These qualities are simply not in the tortoise’s symbolic character. Because the tortoise’s crafty nature is culturally fixed, a narrator trying to make it behave otherwise may lose credibility with his audience. The fact is that symbolic value is ascribed to the character by the culture and the folktale narrator and his audience is customarily led to respect this. However, the narrator is expected to freshen up these characters by engaging them in interesting episodes. The narrator may even borrow episodes from two or more stories and weld them into one story. This is permissible as long as the narrator remains faithful to each character’s symbolic trait. Good narrators can also introduce elements of surprise by manipulating the plot or the motifs instead of tampering with the symbolic tendencies of the characters. This is a major reason narrators have created thrilling versions of a specific tortoise story without compromising the personality of the tortoise. In fact, the tortoise has featured in far more stories than any other single character can lay claim to, and in each story it plays a major role. And the tortoise plays out its symbolic role mostly through its shell. At least 12 different stories in 1000 Folk Stories of Nigeria are weaved around the motif of the tortoise’s patchy shell. They include the stories numbered 281, 332, 343, 366, 371, 372, 388, 396, 499, 502, 591 and 937. In all of these stories, the tortoise is characterized in accordance with its symbolic nature. Symbolic values differ not only from one animal character to another but also from one narrator-audience environment to another. While the tortoise features prominently in the oral narrative of every region of Nigeria, some other interesting animal characters feature mainly in tales associated with a particular linguistic or regional group. A good example is Gizo, a popular character found in many folktales from northern Nigeria. Although the rabbit can play different symbolic roles in other areas of Nigeria, for the Fulani it symbolises cleverness in a self-serving sense. All in all, there is more cultural unity than variations among Nigerian groups. Symbolic characters in Nigerian folktales are not limited to animals. People, spirits, and even some objects are imbued with symbolic meaning. In many tales of this collection, the king is characterized as a symbol of authority and social order. In some stories, however, such as in “The King’s New Robe” (No. 6), the king can diminish his dignified symbolic stature through ignoble or atrocious behaviour. Among the king’s subjects, some categories of individuals are uniquely symbolically represented. They include the old woman (symbolized as a mysterious rescuer or avenger), the juju priest (the communal prophet), the hunter (usually associated with bravery and adventure), and the orphan (a symbol of the triumph of providence over adversity). The orphan’s symbolic character accounts for the reason none of the many tales featuring the orphan in this collection portrays the orphan as a villain. The orphan is almost always a victim of circumstances who ends up triumphant through some fluke of good fortune, supernatural rescue or magical transformation. Women are not so uniformly characterized. While they are represented as caring mothers in some tales, they are painted as vengeful mean antagonists in other tales. The latter picture is prevalent when narrators are characterizing the jealous co-wife. Generally, folktales simply reflect the roles the culture has traditionally assigned to women. The same cultural prerogative also dictates the way the menfolk are characterized in tales. Male and female characters, in general, play different roles – symbolic and otherwise. Even trees are characterised symbolically in many of these folktales. The iroko and baobab trees symbolise mystery, strength, or fertility. “The Child from the Iroko Tree” (No. 878) and “Oluronbi” (No. 894) illustrate the latter symbol. But in spite of the strength of the baobab tree, the soldier ant (characterized in these tales as a symbol of wisdom, industry and resilience) successfully brings down the baobab tree in “The Cock, the Baobab Tree and the Soldier Ant” (No. 941) by attacking its roots. It should be re-stated here that not only characters are of symbolic significance in folktales. Themes, plots and settings can also be used as symbolic tools. Indeed, the formulaic pattern of some plots may serve useful symbolic purposes; and in certain stories involving supernatural elements, the setting of the folktale can be as symbolically important as the characters. But we have dwelt on symbolic characters in this essay because of the central place of the folktale’s characters in initiating and resolving action. One can tell a story without a theme, plot or setting, although it is not likely to be interesting, but it is impossible to tell a story which does not feature at least one or two characters. A folktale is primarily about the characters. This is one of the reasons we opted to use characters in classifying the tales presented in this anthology. Folktale Classification Systems Of the best-known folktale classification systems, none can claim to be adequate enough to be applied universally. These systems are the Aarne/Thompson index (AT index), Aarne/Thompson/Uther index (ATU index), Stilth Thompson’s Motif Index of Folk Literature and Vladimir Propp’s Morphology of the Folktale. Indeed, none of these has captured in its system all the vital aspects of the folktale. While the first three systems listed above concentrate on theme and motif, the third concerns itself with the morphology or structure of the tale. An examination, for instance, of the classification classes adopted by the AT and ATU systems would indicate their limitations and the inadequacy of applying them on a global level. We have tabulated the main AT and ATU classes below.

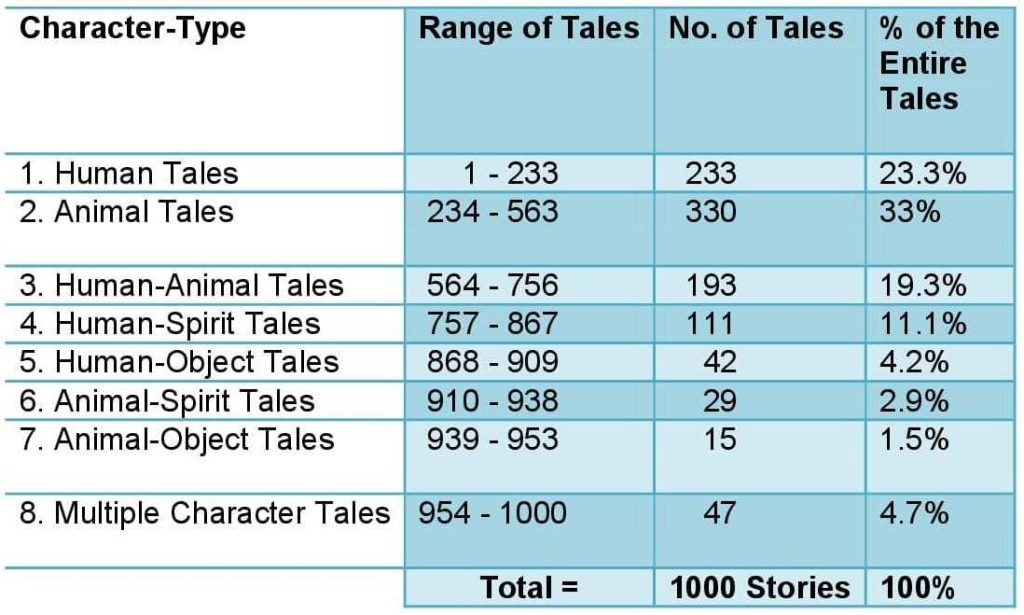

The ATU classification, in spite of its greater thematic space, is inadequate outside the Western world where it has gained some regard as an international taxonomical system. An attempt to fit the 18 classes of the collection, A Selection of Nigeran Folktales: Themes and Settings (edited by Usman) will display obvious inadequacies in certain areas. For instance, in which class would one place enfant-terrible tales? And what about those animal tales that make sense only within the interplay of human and animal characters, in which of the above tabulated classes will they be placed? If the AT and ATU analytical systems were not positioned as global taxonomies, posing the above questions would have been unnecessary. Within the context of their originating Western tradition, these systems (especially the ATU model) are probably adequate for classifying most traditional tales from the Western and, to some extent, Asian worlds. Elsewhere, particularly in Nigeria where we have extensive research to rely on, the ATU index is inadequate, and this is not surprising since tales from Africa were not part of the data used in deriving its classes. And recently, two Malaysian scholars (Harun and Jamaludin) attempted to develop a largely academic “conceptual model that envisions the connections of the three classification systems (Thompson‘s Motif-Index of Folk Literature, the ATU index and Propp‘s Morphology of the Folktale), which displays their cohesive nature to operate as one classification system.” (Brackets mine) While the sort of micro classification proposed by them is not our objective here, it is important to observe that in their parameters these systems are not broad enough to cover tales from every country of the world. Folktale Classification by Character-Types In classifying the 1000 tales studied by this researcher, a character-type classification deemed culturally appropriate for these tales collected from Nigeria was deviced. Since Claude Bremond’s 1966 three-type classification model, further efforts have been made to classify tales by character-type. One of such efforts is the home-grown four character-type model used by Sekoni to classify Yoruba folktales in 1983. Sekoni’s four categories are heroic, non-heroic, anti-heroic and a-heroic character-types (Sesan). A character-type classification was used in grouping the 1000 tales analysed by this researcher. One of the reasons for using this type of classification was the need to celebrate the elements that make folktales vibrate in our memories long after they were told – the characters in the stories! The character-type classification system deplored by the study broadly classifies the 1000 tales into eight groups based on the kind of characters or combination of characters featured in them. The eight categories are as follows:

It should be noted that each of the above tales classification, in being anchored on character-types, represents some basic unifying characteristics of the character drawn from the tales in each category. For instance, all animal tales are unified by the mere fact of being animals, as defined above. Also note that the emphasis here is on a set of characters (e.g, animals) rather than a specific character (e.g, tortoise). This classification, however, allows anyone who so wishes to explore the character traits of single actors (as we did, in this essay, in our earlier discussion on the deployment of the hyena and the tortoise as symbolic characters). Tales Distribution by Character-Types A total of the 1000 folktales collected from different parts of Nigeria, categorized according to their character-types, are distributed into the eight sections of People, Animals, Spirits and Objects: 1000 Folk Stories of Nigeria, as indicated in this Table.

From the above table, one gets the impression that human beings like using animals to portray human behaviour, especially the foibles of individuals and the inequities in the society. Perhaps, this could explain why 33% of the tales (the highest for any singular character type) are animal tales. However, the bulk of the 1000 tales (62.6%) are stories featuring human beings in interaction with human and non-human characters. Conclusion As we have analysed, familiarization with the symbolic value of the characters heightens the reader’s appreciation of the tale and its import. Characters play a central role in generating and developing conflicts in folktales, and conflicts are what make folk stories interesting to the audience. In whichever way conflicts are resolved, happily or unhappily, they ultimately teach some morals. These morals, no matter the cultural root of the tale, are usually universal truths. Understanding the social values represented by the characters enhances the reader’s enjoyment of the story and the kind of moral truths drawn from it. Works Cited Bernardo, Karen. “Characterization in Literature” (http://www.storybites. com) Bremond, Claude. “La logique des possibles narratives”. Communications, vol. 8, no. 1, 1966, pp. 60-76. Carroll-McQuillan, Synia. “Folktales: The Mirror of Society”. http:// www.yale.edu/ynhti/curriculum/units/1993/ 2/93.02.02.x.htm) Choudhury, Saradashree. “Folklore and Society in Transition: A Study of The Palm Wine Drinkard and The Famished Road”, African Journal of History and Culture, vol.6, no. 1, January 2014, pp. 3-11. Fischer, J.L. “The Sociopsychological Analysis of Folktales”. Current Anthropology, vol. 4, no. 3, University of Chicago Press, June 1963, pp. 235-295. Habila, Helon. “The Embrace of the Snake”. In Duve Nakolisa, ed. Through Laughter and Tears: Modern Nigerian Short Stories. Klamidas Books, 2015. Harryizman Harun and Zulikha Jamaludin. “Folktale Conceptual Model Based on Folktale Classification System of Type, Motif, and Function”. Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Computing and Informatics, Paper No. 118, Universiti Utara, 2013. Jung, Carl. Man and His Symbols. Doubleday, 1964, p. 93. Nakolisa, Duve, ed. Through Laughter and Tears: Modern Nigerian Short Stories. Klamidas Books, 2015. Obiechina, Emmanuel. Culture, Tradition and Society in the West African Novel. Cambridge UP, 1975, p. 27 Okediran, Wale. “Just One Trip”. In Duve Nakolisa, ed. Through Laughter and Tears: Modern Nigerian Short Stories. Klamidas Books, 2015. Propp, Vladimir. Morphology of the Folktale, 4th ed. University of Texas Press, 1998. Sesan, Azeez Akinwumi. “Yoruba Folktales, the New Media and Postmodernism”. Khazar Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, vol.17, no. 2, Khazar UP, 2014. Thompson, Stilth. Motif Index of Folk Literature, Vol. 16. Indiana UP, 1966. Usman, Bukar, ed. A Selection of Nigerian Folktales: Themes and Settings. Klamidas Books, 2016. Usman, Bukar, ed. People, Animals, Spirits and Objects: 1000 Folk Stories of Nigeria. Klamidas Books, 2018. |

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||