Global Online Journal of Academic Research (GOJAR), Vol. 3, No. 3, June 2024. https://klamidas.com/gojar-v3n3-2024-05/ |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Environmental Scarcity and Violent Conflict in North Eastern Nigeria By Livinus Nwaugha, Banwo A. Irewunmi & Odunusi Kolawole Olu ABSTRACT Environmental scarcity plays a significant role in triggering violence in many parts of the world and it is the position of this paper that it is a direct cause of violent conflicts in Nigeria’s North East geo-political zone. Evidence emanating from research conducted in the course of this study contradicts the view held by key Western analysts that although the adverse effects of climate change might be an underlying cause of violent conflicts, it is never a direct cause of such conflicts. Relying on secondary sources of data collection and structured interviews with knowledgeable persons residing in the affected states of the North East, this study investigated the issue of environmental scarcity and its direct link to violent conflicts in the North East zone of Nigeria and came up with findings that validate its position that environmental scarcity, in many instances, can be the direct cause of violent conflicts, not merely a contributory factor. Patterns of climate-induced violent conflicts, particularly those involving farmers and herdsmen in the North East, were identified, and possible lasting solutions to the conflicts were proffered by the study. Keywords: environmental scarcity, violent conflict, North East, Nigeria, farmers, herders INTRODUCTION Northern Nigeria is faced with several environmental challenges that threaten the ecosystem of the region, particularly that of its North-Eastern part, and make the eruption of violent conflicts more likely to occur in the area. Research has shown that “environmental scarcity leads to certain destabilizing social effects that make violence more likely” (Kennedy 2001). Environmental scarcity plays a significant role in triggering violence in many parts of the world and it is the position of this paper that it is a direct cause of violent conflicts in Nigeria’s North East geo-political zone. This refutes the view of Kennedy (2001) that “Environmental scarcity is never the sole cause of conflict, but it is often an aggravating or contributing factor” and the claim of Martin, Blowers & Boersema (2006) that “environmental scarcity rarely creates fresh social cleavages”. Some local observers share this view which is generally held by Western analysts. Agwu (2010) holds the opinion that environmental scarcity is not a direct cause of violent conflicts. This study, however, argues that the adverse effects of environmental scarcity can predispose affected parties towards violence, and are known to have done so in North Eastern Nigeria. When someone or a group of persons, for example, feel that land which they could have utilized for farming or infrastructural project has been grabbed by another party, there will be feeling of animosity towards that party, and this can directly lead to mutual hostility or violent conflict. METHODOLOGY Utilizing secondary sources of data collection and structured interviews, this study will examine the subject of environmental scarcity and its direct link to violent conflicts in the North East zone of Nigeria to prove and reinforce its position that environmental scarcity, in many instances, can be the sole or direct cause of violent conflict, not merely a contributory factor. A mixed method of enquiry is used in this study. Primary data were sourced through semi structured interview of eighteen (18) respondents purposively interviewed on the topic of environmental scarcity and violent conflicts in the North East. The eighteen (18) respondents were segmented and selected from the six states in the North East geopolitical zone, namely, Adamawa, Bauchi, Borno, Gombe, Taraba, and Yobe. Three (3) persons were selected and interviewed from each of the six states. Secondary data were sourced from periodicals, newspapers, journals and the internet. DEFINITION OF TERMS Environmental Scarcity The term, “environmental scarcity” refers to the scarcity of an environmentally-generated and renewable resource, such as land, wood and water, due to “reduced supply (depletion or degradation), increased demand and/or increasing inequality of distribution” (Martin et al, 2006). Kennedy (2001) identifies three kinds of environmental scarcity, namely:

Everywhere in the world where there is shortage of natural resources the available ones are scrambled for by individuals and groups, and competition for scarce resources can directly or indirectly lead to conflicts (UNEP, 2012). Violent Conflict To understand the scope of our discussion, we need to define the term, “violent conflict” and see what connections it has with similar terms, such as “armed conflict” and “war”. As stated by CGIAR, the global body that unites international organizations concerned with food security research, “A violent conflict involves at least two parties using physical force to resolve competing claims or interests” while “An armed conflict is a contested incompatibility that concerns government and/or territory where the use of armed force between two parties, of which at least one is the government of a state, results in at least 25 battle-related deaths in one calendar year”. According to the UK Save the Children organization, “Conflicts are part of war, though not every war sees actual conflict, nor is every conflict connected to war”. Since the security situation in the North East involves diverse kinds of conflicts, including the protracted Boko Haram insurgency, it is important to note that the latter and similar armed struggles are excluded from the scope of this discussion. Our topic is narrowed to violent conflicts between parties in that zone contesting for renewable natural resources that have become scarce due to climate change or that have been degraded by destructive human activities. ENVIRONMENTAL SITUATION IN NIGERIA Nigeria has a total land area of 923,768 km² and is endowed with diverse ecosystems its government and huge population have the responsibility of conserving and managing. According to the 2016 revised National Policy on the Environment (henceforth NPE 2016), the country’s ecosystems include air and atmospheric resources, fresh water and wet-land ecosystems, coastal and marine ecosystem, mountain ecosystems (Mambilla/Plateau), arid and semi-arid ecosystems, and forest ecosystems. Others are biodiversity and wildlife resources, livestock and fishery, land resources and land use (desertification, land degradation and drought), soils, oil and gas, and minerals. Studies have shown that disequilibrium in these ecosystems stems from the activities of human beings. Onuoha, Chinedu & Ochekwu (2022) have noted that the ill effects of “man’s activities on the environment include urbanization, deforestation, improper waste disposal, unregulated agricultural practices, among others, which have resulted in desertification, pollution, ocean acidification, health issues, global warming, and ecosystem instability”. Further negative impacts of the activities of human beings on the environment include overpopulation and flood (Omofonmwan & Osa-Edoh 2008). Abuse or misuse of the environment is associated, among other causes, with the exploration and exploitation of natural resources as well as with industrial activities in both Southern and Northern Nigeria. Oil exploration, notably, has adversely affected the ecosystems of the southern region of Nigeria, particularly those of the South-South states of Bayelsa, Rivers, Delta, Cross-River and Akwa-Ibom. It began in 1956 when oil was first discovered in large quantities at Oloibiri, Bayelsa State; oil was subsequently discovered and explored in other states of the geo-political zone. Since then, the natural habitat of the zone has been in disarray such that aquatic resources and wildlife in general are threatened with extinction while farmlands and the sub-regions vegetation are devastated. Effects of frequent oil spillage and unsustainable exploitation of the area’s oil and gas have made it increasingly difficult for fishermen and farmers to earn a living, thereby exacerbating the environmental scarcity situation of the area. Many of the environmental difficulties in northern Nigeria are linked to drought and desertification. Summarizing the environmental state of affairs in Nigeria, NPE (2016) notes: Nigeria’s environment is under increasing threat from human activities and natural disasters. There are already certain ominous problems with the environment and visible scars associated with the destruction of the natural resource base (land, water and air) upon which all life depends are being noted. The country’s large population of about 170 million and its rapid growth rate of 2.8 per cent are contributing to its environmental degradation. SOCIAL AND ECOLOGICAL ENVIRONMENT OF THE NORTH EAST Since the North Eastern zone of Nigeria is the focus of this research, we will discuss the social and ecological environment of the zone in this section in order to see how it might be associated with the eruption and prolongation of violent conflicts in the area. Social Environment of the North East The North East geopolitical zone of Nigeria is made up of Adamawa, Bauchi, Borno, Gombe, Taraba and Yobe states. Before 1991 the states were known as Bauchi, Borno and Gongola states. In 1991, Borno State was divided into Borno and Yobe states while Gongola State was divided into Adamawa and Taraba states. Bauchi state, in 1996, was divided into Bauchi and Gombe states (Scan, 2016:154). According to Scan (2016), the essence of the split was to bring government closer to the people. The region has over 500 ethnic groups (Scan, 2016); the area’s many languages include Kanuri, Fulani, Hausa and Fulfulde. The population of the area is estimated to be 32 million (NBS, 2023), many of whom are engaged in farming, fishing and livestock. Islam, Christianity and traditional religion are the notable religious groups of the area. Ecological State of the North East The North East has challenging environmental problems that include “acts of God” occurrences such as drought, desertification and the drying up of Lake Chad basin – an important source of water supply to the pastoralists and farmers of the area. The major environmental hindrances of the North East are substantially man-made, and they include overpopulation, deforestation, destruction of the area’s fragile vegetation by herdsmen, land degradation, and air pollution. Both natural and man-made factors combine to complicate the environmental situation of the North East where, on yearly basis, “the sand dune is progressing at a mean annual rate of about 15.2 km2” (UNOOSA 2022). Bolarinwa (2019:278) has also stated that several kilometers of land are lost to desertification. Although climate change is a universal phenomenon, it affects the nations of the world in different ways. According to NPE (2016), Nigeria is strongly predisposed to severe negative impacts of climate change due to the nature of its economy, weak resilience and low adaptive capacity. Much of the economy is dependent on climate sensitive resources. For example, the agriculture sector (crop production, livestock and fishery) and forestry which employ up to 70% of the workforce and contributes about 22% of the rebased GDP is very climate sensitive. Climate change is responsible for the receding plight of the Lake Chad Basin, a great source of water for irrigation in the North East where desert encroachment has reduced the size of the zone’s arable land and grazing resources. ENVIRONMENTAL SCARCITY AND VIOLENT CONFLICTS IN THE NORTH EAST Since 1980, with the recession of the Lake Chad basin occasioned by climate change, there has been mass movement of herders and farmers within and out of the North Eastern part and this has been causing intense competition for the use of the available land. The convergence of these groups has generated altercations rather than amity as herders and farmers migrate away from arid lands towards the south. This southward movement of herders to southward has not been without its own challenges in the Southern states of Anambra, Enugu, Delta, Edo and Ondo. Effects of desert encroachment in Nigeria are felt mostly in the North. The vast areas encroached by the desert become barren land and push farmers and herders to relocate to safer areas. However, the most desert-prone areas in the North are found in the Maiduguri and Yobe axis and account for the great number of internally displaced persons in those areas as well as for occupational migrations among the farmers and the herders. The herders who are nomads would usually migrate to another destination and settle, and because they do not practise ranching system, their animals stray to farm lands and destroy crops, and when the farmers resist the encroachment, violent conflicts frequently ensue, and many of such conflicts have often led to horrible reprisal attacks by the herdsmen. Nigerian pastoralists have said that Nigerien and Chadian nomads, who found their way into Nigeria as a result of the drying of the Lake Chad Basin, were mostly the perpetrators of these cruel reprisal attacks. Additionally, since the North-East region depends largely on land as the source of their livelihood and the increase in population has continued to exert pressure on land for food crops and grazing of cattle, there is a great deal of competition between the herders and farmers for the use of the available land. The challenge is that both the farmer and herder need the land for sustenance. Another dimension is the indigene-settler squabble. According to one viewpoint, the farmers see themselves as the indigenes who are entitled to the use and cultivation of the land while the herders, who are nomads, are seen as the settlers and usurpers of the land (Ahamadu, 2011). But this is not always the situation, especially in those circumstances where violence had erupted because the herders had failed to restrain their cattle from destroying economic crops. Part of the problem is the grazing reserve laws of 1965 and national policy on agriculture of 1988 (Ahamadu, 2011); much of the grazing routes envisaged by the 1965 law are no longer forests as they have been turned into built environments for housing, roads and other infrastructural purposes. Only the establishment of ranches, as obtains in many parts of the world, appears to be the most viable solution to the farmers-herdsmen conflicts. The frequency of environmental scarcity-induced violent conflicts in the North East and other parts of Nigeria has attracted the attention of governmental and non-governmental organizations. In 1976, the National Emergency Relief Agency (NERA) was established. It later metamorphosed into National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA) by Act 12 as amended by Act 50 of 1999. National Emergency Management Agency is the agency of government responsible for resettling persons affected by violent conflicts and natural disasters. However, since 2009, NEMA has been saddled with the responsibility of handling cases of internally displaced persons caused by environmental scarcity-related violent conflicts in Nigeria, especially in the North East. This is a huge responsibility; according to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs: “the North East region would require over 1.6 billion U.S Dollar in order to provide shelter, health care, as as well as to ease hunger within the region”. According to Mba (2017), internal displacement crisis in the North East is caused by natural disaster, communal clashes and Boko Haram insurgency, with Boko Haram accounting for 85.65% of the cases, communal clashes 13.37% while natural disaster accounts for 0.99% (Mba, 2017). In order to deal with this problem, the Kampala Convention of 2009 for the protection and assistance of internally displaced persons in Africa spelt out the following objectives:

It is on the basis of the above that National Emergency Management Agency, in line with the provisions of the AU Kampala convention, was established to perform the following functions:

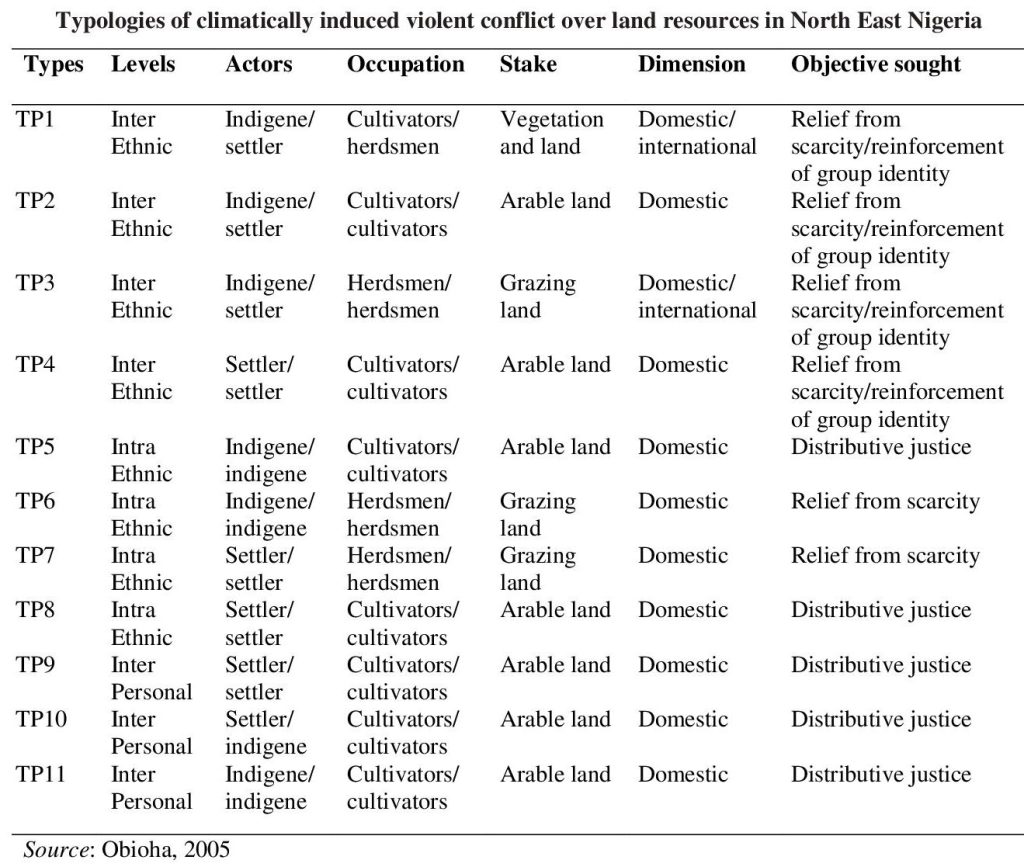

Thus, NEMA’s functions synchronize with United Nations charter and Kampala convention which emphasizes the protection of the internally displaced persons in line with the international human rights laws that mandated the government to protect the rights of internally displaced persons and to intervene in the welfare of the victims. To support the above objectives, the governors of the states in the North East signed memorandum of understanding (MOU) with NEMA to enable NEMA supply food and non-food items to the conflict-affected states of Adamawa, Borno and Yobe as part of federal government’s efforts to cushion the humanitarian challenges faced by the internally displaced persons (Daitti, 2016). According to Daitti (2016), NEMA is expected to provide adequate intervention support in IDPs camps to reduce the plight of IDPs in Maiduguri, Adamawa and Yobe. Despite the bold initiatives of NEMA, it continues to encounter systemic setbacks that challenged its capacity to function optimally as an interventionist agency; these setbacks include lack of capacity and resources, poor record keeping of the actual number of the internally displaced persons, poor delivery and distribution of relief materials and diversion of funds and relief materials for private use. Types of Climate-Induced Violent Conflicts in the North East An important study by Obioha (2008) associated effects of climate change in the North East with certain types of violent conflict in the area: In the recent times, due to the increasing rate of global warming, the northeast region of Nigeria has been experiencing continuous climatic change characterized by drastic reduction in rainfall, increase in the rate of dryness and heat, which makes it a fast growing arid environment, with depletion in the amount of water, flora and fauna resources on the land. In response to the pastoral and arable farm occupational needs of the people, there has been continuous population drift southward where there are more fauna, flora and water resources. Such southward move, Obioha stated, is responsible “for the conflict between Tivs and the pastoral Hausa/Fulani people in June 2001 (IRIN-WA 18 July 2001). Also in March 2003, many people were killed when a group of heavily armed men attacked the town of Dumne, Bornu state in northeastern Nigeria.” He said the attack was “not unrelated to a violent dispute over grazing land in September 2002 between local people, who are mainly farmers, and nomadic herdsmen”. In Obioha’s view “The decreasing availability of physical, environmental and land resources such as clean water, good agricultural land for arable and animal husbandry could create a condition of ‘simple scarcity’, ‘group identity’ and ‘deprivation’ in the area, (Homer-Dixon, 1994) that may provoke violent conflicts of high magnitude due to population movements and scramble for the available resources.” Specifically, Obioha’s study sought to locate “the role of scramble for flora in conflict generation among the sedentary arable farmers and the migratory herdsmen/pastoralists in the area” and concluded that the “contention is either arable land or fresh vegetation grazing land…while the objective sort may be for distributive justice…to reinforce group identity or search for relief from scarcity when the occasion arises or both”. Obioha (2008) identified 11 types of climatically-induced violent conflicts in the North East; interestingly, subsequent climate-related conflicts in the area have followed the pattern outlined in his typologies table, shown below.

Obioha used his typologies to characterize inter-ethnic violent conflicts which took place in the North East in the early 2000s. Those conflicts included 2000s Billiri uprising, 2002’s Song crisis and Dumen village crisis, and Yelwa/Shendam/Wase crisis of 2003. Others were Demsa, Lamurde, Madagali, Bali, and Numan crises of 2005. All of these crises took place long before the Boko Haram insurgency erupted in the area. Unlike Boko Haram, these conflicts, and similar communal disturbances that subsequently took place, were not primarily caused by religious intolerance; rather, they were violent conflicts that arose “over the scramble over some types of resources in particular: river water and agricultural productive land. These renewable resources by implication seem particularly likely to spark conflicts because their scarcity is increasing rapidly without commensurate replenishment” (Obioha 2008). Such conflicts have generated a large number of internally-displaced persons (IDPs) in the area. According to Lawal (2018:53), about 22.5 million people have been displaced by environment scarcity- and conflict-related problems since 2008. Negative effects of climate change in the North Eastern part of the country continues to shape migration patterns in the region (Lawal, 2018), with more and more persons migrating southwards in search of arable and grazing land, moves which occasionally provoke violent conflicts. According to UNEP (2012), violent conflict is likely to occur in communities where environmental scarcity is increasingly a critical problem. The UN agency explains that environmental scarcity occurs where supply of renewable resources such as water, forest, ranchland and croplands are not sufficient to meet the demands of those who need them for their occupational or daily survival. UNEP further observes that wherever this scenario prevails, the outcome would be stiff competition which might lead to violent conflict. Although violent conflicts, as we have shown, can be a direct result of environmental scarcity, some conflicts, even when climatically-induced, can broaden into ethnic or religious clashes, as they may be used to settle long-standing grievances, but this should not cancel the fact that the main trigger of the crisis was scarcity of renewable natural resources. So, a violent conflict triggered by environmental scarcity can be used by any of the warring parties not merely for the purpose of achieving “relief from scarcity” or “distributive justice” but also for “reinforcement of group identity”. Findings and Discussion As earlier mentioned, eighteen (18) respondents were selected and purposively interviewed from the six (6) states that make up the North eastern part of Nigeria, namely, Adamawa, Bauchi, Borno, Gombe, Taraba and Yobe. Respondents #5, #6, #7, #1,#2 and #8 categorically stated that climate change is largely the cause of environmental scarcity in the North Eastern part of Nigeria. They further maintained that the drying up of Lake Chad Basin caused by climate change, and the 2012 opening of the dams that submerged farm lands, made many people vulnerable to harsh effects of the climatic crisis. They also said the desert encroachment caused by climate change in the north Eastern part of Nigeria is the source of farmer-herder clashes that left scores of people displaced and several farmlands abandoned. Respondents #3, #4, #9, #10, #12, #14, #16, and #18 blamed the situation on natural disasters, such as volcanic eruptions, desertification, gully erosions, tidal wind as well as over population; these, they said, dislocated the ecosystem in the North East. The respondents further opined that year in year out the metrological agency makes predictions/forecast on the weather condition and its likely consequences but the Nigeria government often failed to take pre-emptive measures. They cited Dubai, a desert region, which has now become the tourist heaven of the world. The last set of interviewees, respondents #11, #13, #17 and #15, attributed environmental scarcity to government’s insensitivity and advised government and the metrological agency to work in concert, so as to provide remedial measures should there be flood; they also said irrigation facilities should be provided for the desert prone north-eastern part of Nigeria, and that proper ranching system should be introduced to forestall incessant farmer-herder clashes that often led to loss of lives and destruction of farm crops and livestock. Conclusion Environmental scarcity is a major problem confronting developing countries, including Nigeria, especially North eastern part of Nigeria. In spite of the response of government and international agencies, the problem has remained prevalent and devastating, often leading to violent conflicts. The study revealed that environmental scarcity, conflicts and insecurity are interrelated in the North Eastern part of Nigeria and constitute the direct cause of farmer-herder clashes in the region that have disrupted food production, unleashed hunger, killed many people, and left thousands of people internally displaced. The study concludes that environmental scarcity is an emerging global challenge governmental and non-governmental agencies all over the world should frontally address, and that the best way to start is to deal with regional hot spots, such as Nigeria’s North East, where the problem of environmental scarcity is already causing persistent violent conflicts. References Agwu, F.A. (2010). Impact of Climate Change on Nigeria’s Foreign Policy. In Eze, O.C. & Oche. O (Ed), Climate Change and Human Security in Nigeria, NIIA, Lagos Ahmadu, I. (2011). Farmer-Grazier Conflict View of a Livestock Worker on ‘Official’ Interpretation and Handling. In Ate, B.E. & Akinterinwa, B.A. (Ed), Cross-border Armed Banditry in the North-east: Issues in national security and Nigeria’s Relations with its Immediate Neighbors. NIIA, Lagos. BolarinwaJ.O. (2010). Clash of Culture: Muslim-Christian violence in Nigeria and its implication for political stability. In Albert I. O. & Olarinde O.N. (ed), Trends and Tension in managing conflict. John Archer, Ibadan. Danjuma, I.A. (2017). Globalization and the Dynamics of Intra-State conflicts or Africa. In Gwaza, P.A. & Ubi, E. N. (Ed), Nigeria in Global governance, peace and security, essay in Honour of Prof Joseph. Habila Golwa Honeybees Ltd, Lagos Danjuma, I.A. (2014). National Security and the Challenges of Terrorism in Nigeria. In Nwoke, C.N & Oche, O. (Ed), Contemporary Challenges in Nigeria, Africa and the World. Lagos. https://climatesecurity.cgiar.org/data/ConflictDefinitions.pdf https://www.savethechildren.org.uk/what-we-do/conflict-war #:~:text=A%20conflict%20is%20a%20fight,every%20conflic t%20connected%20to%20war. https://www.unoosa.org/documents/pdf/psa/activities/2022/U N-Austria/Mahmoud_Ibrahim_ Mahmoud.pdf Kennedy, Bingham Jr. (2001). Environmental Scarcity and the Outbreak of Conflict. https://www.prb.org/resources/ environmental-scarcity-and-the-outbreak-of-conflict/#:~:text =Environmental%20scarcity%20refers%20to%20the,such% 20as%20freshwater%20or%20soil. Lawal, O. (2018). Climate Change, Migration and International Protection Laws. Nigerian Journal of International Affairs. Volume 44, Number 1&2, 2018 PP 46-62 Magaji, Y.M.M. (2011). Strategies for Effective Confidence-Building and Peace in Nigeria’s North-East zone: Taraba State as a case-study In Ate, B.E. & Akinterinwa, B.A. (Ed). Cross-border Armed Banditry in the North-East: Issues in National Security and Nigeria’s Relations with its Immediate Neighbors. NIIA, Lagos. Martin, A., Blowers, A. & Boersema, J. (March 2006). Is environmental scarcity a cause of civil wars? Environmental Sciences; 3(1): 1-4. DOI: 10.1080/15693430600593981 Mba, R. (2017). IDPs and the Need for Reinterpretation. https://www.medium .com @ rurhmba//the-plight-of-internal-displaced-persons-idps-and-need-for-reinterpretation-B7555C212f37. Mohammad, A. (2011). Threat Perception, Rationalization and Response to Internal Security, in Nigeria’s North-East zone In Ate, B.E & Akinterinwa B. A. (Ed), Cross-border Armed Banditry in the North-east: Issues in National Security and Nigeria’s Relations with is Immediate Neighbors. NIIA, Lagos. National Policy on the Environment (Revised 2016). https://faolex.fao.org/docs/ pdf/nig176320.pdf Nigerian Bureau of Statistics (2023). Obioha, E. E. (April 2008). Climate Change, Population Drift and Violent Conflict over Land Resources in North Eastern Nigeria. Journal of Human Ecology 23(4):311-324. DOI:10.1080/09709274.2008.11906084 Omofonmwan, S & Osa-Edoh, G. (January 2008). The Challenges of Environmental Problems in Nigeria. Journal of Human Ecology, 23(1). DOI:10.1080/09709274.2008.11906 054 Onuoha, C. A, Chinedu, N & Ochekwu, E. (July 2022). Environmental Challenges Awareness in Nigeria: A Review. African Journal of Environment and Natural Science Research, 5(2):1-14. DOI:10.52589/AJENSR-SAIRDC4K United Nations Environmental Program (2012) Report. |

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||