Global Online Journal of Academic Research (GOJAR), Vol. 3, No. 3, June 2024. https://klamidas.com/gojar-v3n3-2024-04/ |

|||||||||||

|

Music and Charismatic/Pentecostal Worship: Nigerians’ Instrument of Achieving Peace of Mind in the Midst of Difficulties By Jude Toochukwu Orakwe ABSTRACT Nigeria has passed through lots of social upheavals, economic difficulties and political instability ever since her independence in 1960. Nigerians have suffered and continue to suffer in patience! But one can also recall that similar – if not lesser pains – experienced in some Arab countries gave rise to the so-called Arab Spring. Among the causes of the Arab Spring are: political corruption, human right violations, inflation, kleptocracy, unemployment and ultimately the self-immolation of one Mohammed Bouazizi in Tunisia on 17 December 2010. In summary, the so-called Arab Spring affecting countries like Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, Yemen, Syria, etc. was a chain of unprecedented violent revolution against the socio-political status quo. The question remains: why has Nigeria not erupted in the flames of revolution given that the same causes of the Arab Spring – and even much more – have always remained with Nigerians? Why have Nigerians not risen up against the oppression and insensitivity of the political/ruling class? Answering this question in this paper, by analyzing Nigerians’ personal experiences using hermeneutical and phenomenological theories and methods, I argue that Nigerians have employed and still employ charismatic/Pentecostal music as their instrument of negotiating their way through all the difficulties they go through and achieving peace of mind in the midst of these difficulties. Keywords: Charismatic/Pentecostal movement, worship, music, negotiation, phenomenological method

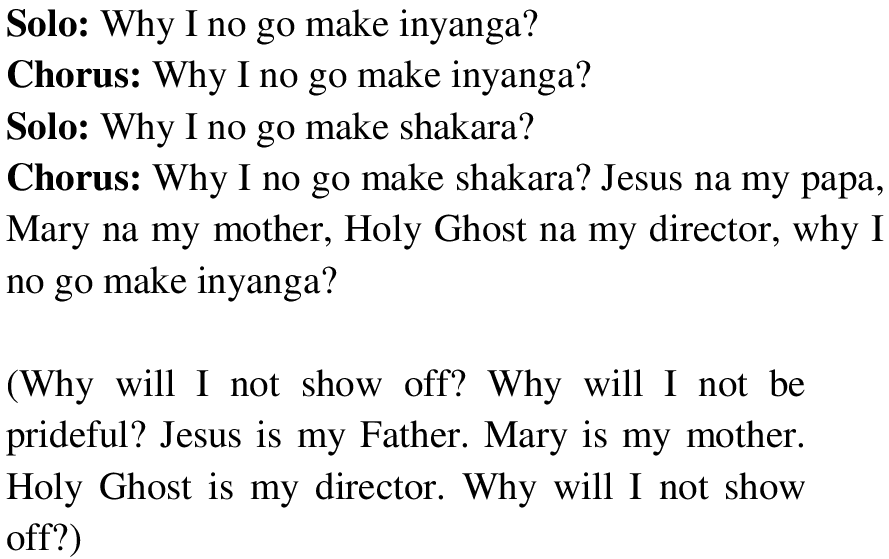

INTRODUCTION Narrative theology stands as one of the backbones or mainstay of Pentecostal/charismatic Christianity in Nigeria. Conceptually speaking, Harvey defines narrative theology as a theological current that: …examines the relationship between narrative as a literary form and theological reflection. It is a relationship derived from the basic observation that it is in reading, telling and interpretation of narratives that humans derive communal and personal identity as well as provide for meaningful activity in the world (Harvey 2008, p. 598). Harvey’s definition serves to show that narrative theology, among other things, embraces personal-faith stories and experiences. In this guise, one can easily observe that narrative theology influences not only the manner of preaching in Nigerian churches, especially in Pentecostal/charismatic prayer meetings, but also the framing of songs that are often used for worship in Nigerian Christian communities. My emphasis in this essay is on the aspect of composition and use of call-response gospel choruses in Nigerian churches. ETHNOGRAPHIC REPORT Before proceeding, I want to give an ethnographic account of a live church worship that I experienced on October 31, 2012 as I was preparing to embark on my doctoral dissertation research in the field of ethnomusicology. It was at the Holy Trinity Catholic Church, Isashi, Lagos. There was the burning of the written petitions of the church members by the priest at the end of what is known as the October devotion. As the burning was being done, there came up a most energetic outburst of praise-worship songs led by one Ngozi (an Igbo lady married with two children). I had never seen such a gifted chorus leader as Ngozi. Somebody informed me that normally, as soon as she starts singing, she goes out of herself. “A kind of entering into altered state of consciousness?” I queried myself. Probably so, because during the church service, she seemed to have entered into the world of what she was singing (See Titon 2008, p. 31ff) and freely manipulated the singing to and fro, tonally bending her voice with such ease and moving from one song to another. She instructed the congregation on what to do: dancing, clapping, making inyanga (exhibiting pride in a “holy way”) and the congregation obeyed in chorus with an astounding blind obsequiousness. Two songs in Pidgin English performed to the accompaniment of percussive instruments were especially outstanding. The first has the following lyrics:

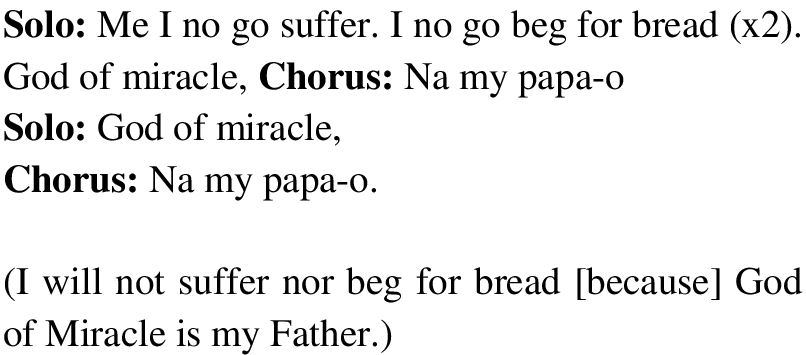

The second song goes thus:

These songs were rendered with a highly polyrhythmic and heterophonic sound of Nigerian native instruments that kept the worshipping audience rocking with energetic body movement and worship dancing. The whole scenario triggered off in me a reflection that has marks of phenomenological epoche. I sensed the need to treat the religious performance of the Isashi worshippers as an “important and critical data” (Stone 2008, p. 165), while phenomenologically bracketing all “prejudices and schematisms” (http://www.zenit.org). DEALING WITH PREJUDICE Previously, because of my philosophical and theological formation, I used to regard these songs as couched in vulgar and liturgically unacceptable language. I used to reason about the wrong theology inherent in the first song: Why I no go make inyanga, which addresses Jesus as “Papa” whereas, as the second Person of the Blessed Trinity, he is the Son. One version of the song addresses the Holy Ghost as “my brother” which sounded to me like arrant nonsense. With regard to the second song, I saw it as expressing an irrational craze for miracle in its persistent invocation of the “God of miracle… na my papa,” especially given its insistence “Me I no go suffer…” The fact that these two songs were couched in Pidgin English – in my reasoning – did not help matters given that Pidgin English is often regarded in Nigeria as language of the illiterate and uneducated folks! However, within the particular context of the worship at Holy Trinity, Isashi, I was struck to the depth by the sincerity and unpretentiousness with which the members of the congregation rendered and physically dramatized these songs under the musical leadership of Ngozi, who seemed to wield an uncanny moral sway over the worshiping participants. It was a performance that was coming from the profundity of their experiences both as individuals and as a community. Can these simple and sincere folks just be dismissed with the wave of hands just on the basis of philosophical or even theological ratiocination that deliberately fails to take into consideration their unique sitz-im-leben? This calls into focus the necessity of ethnographically appraising their culturally founded system of worship with the approach of phenomenology. PHENOMENOLOGIST APPROACH Ethnomusicologists have felt much drawn to “sociological phenomenology” that evolved in the literary works of Alfred Schutz (1971a, pp. 159-178, 1979b, pp. 179-200). Musically speaking, sociological phenomenology makes two assumptions, namely: “Music can be regarded as occurring within a ‘finite province of meaning.’ Durée, or inner time, is the central focus of the musical experience” (Stone 2008, p. 168). The first assumption implies that music occurs in a marked-off world that has its own logic apart from the logic of everyday manner of living. For example, in music, motion and time are virtual but in the world of practical everyday living, these spatio-temporal factors are real. In speaking of inner time, Schutz refers to that qualitative experience of time that defies quantification. Schutz’s characterization of qualitative time experience is especially, though not exclusively, true of African religious music. It is true of worship performance at Holy Trinity, Isashi, because from my observation, the central concern of the worshipers was not how long the worship lasted but its quality. With the quality established by the singing, there was – in my opinion – a flight from the normal chronometric time into the inner qualitative time of the music such that left to the worshipers, the worship could as well last into the night. I then saw it as my duty as an ethnographer to hold on to “this qualitative time as a primary point of analysis [given that] it is here that experience is at its most intense” (Stone 2008, p. 168). This flight into qualitative time is very pivotal for understanding how Nigerians religiously use charismatic/Pentecostal worship and religious music making as a tool of negotiating through their life difficulties. By flight into the virtual time of religious music, social problems and even the exigency to tackle these problems headlong are literally swept under the carpet or flushed into the septic tank of oblivion. TOWARDS A HERMENEUTIC RE-EVALUATION Now, armed with the tool of phenomenology – with its emphasis on shelving off prejudices – the crucial question is: how does one interpret the music making I experienced? How does one interpret lots of the charismatic and Pentecostal music making going on in many of the mainline churches and minor denominational sects? I was in Isashi Lagos for more than a month, between the middle of October and late November in 2012 (because of the delay in the processing of my visa to Italy) and also for a few weeks between February and March 2013 (when I came back to renew my visa) and personally experienced the difficulty of living in an area that is usually full of flood and stagnant water, riddled with the problem of epileptic supply of electricity together with the difficulty of general transportation. It then dawned on me, without much discursive reasoning, what the worshiping congregation meant as they were singing: “Me I no go suffer…” or “Why I no go make inyanga…?” These songs, in my calculation, constitute packages of condensed narrative theology in which the people of Isashi tell the stories of their life in the midst of suffering, a life that no longer depends much on the political class that often disappoints the people in being unable to provide for their basic necessities but only on God, in whom and with whom “they make shakara.” The above understanding and explanation of my experience of the worship singing in Isashi church serves to open the question of how Nigerians go through their difficulties in life aided by their recourse to church worship songs. Adducing the reasons for the flowering of the charismatic/Pentecostal movement in Nigeria and citing Marshall, Rosalind Hackett contends that such growth has much to do with the political trajectory of Nigeria, especially given the recurrence of corrupt and inept civilian government as well as illegal incursion of the military into politics. Hence, “religious organizations have provided outlets for expression and action – but more cathartic and veiled, rather than of a directly critical nature.” Further, she argues: “economically… Nigeria [has] gone through hard times with Structural Adjustment Programs and falls in commodity prices, whether oil or gold. ‘Only God can save us’ is a common refrain” (Hackett 1998, p. 260). The phenomenological reality is that the attitude of ‘only God can save us’ gets crystallized in various forms of call-response gospel choruses that one hears in various churches in Nigeria. I will briefly discuss three genres of call-response that reflect efforts by Nigerians to overlook or look beyond the various problems they encounter in their daily difficult life as Nigerians. SONGS OF PRAISES According to Bob Sorge: Praise is preoccupied with who God is and what he has done. It focuses on both his incomparable character and his wondrous acts on behalf of his children. When God does something glorious for us, we love to lift high praises. And yet praise is not simply our thankful response to his provision; praise is also very fitting even when we have no specific gift of God in mind. He is worthy to be praised solely for who he is (Sorge 2001, p. 2). In the charismatic/Pentecostal worship of Nigerians, praise songs are performed uninterruptedly at the beginning of a fellowship session, with the accompaniment provided by a guitar band on big occasions or indigenous instruments in smaller gatherings. When there are no instruments, then clapping of hands becomes the accompaniment. The singing at this point tallies with what Barry Liesch describes as “free flowing praise” in which “songs are often stitched together into a medley by improvisational playing and modulation to create a sense of seamlessness, of one song flowing into the next” (Redman 2002, p. 35; See Liesch 1996). Among the praise songs that celebrate the essence of God would be pieces like (a) Since I was born, but now I am getting old, I have never seen my Lord changeth, Brothers (sisters) have you seen him, No nonono, since I was born, I have never seen my Lord changeth, (b) Lift him up, higher, Lift him up, higher, the Lord is good I will lift him up higher, everywhere I go I will lift him up higher, (c) Mmamma diri gi O Chineke, mmamma diri gi O Onyeoma (Praise be to you, O God, Praise be to you, Righteous One). In Pidgin English, there is also the song: Jesus na You be Oga, Jesus na You be Oga, All other gods na so so yeye, Every other god na so so yeye (Jesus, you are the Lord [twice]. All other gods are false, every other god is false). The last song exalts Jesus as the only true God and Lord. Note that the lyrics could be used as a veiled reference to those powerful politicians who pretend to parade themselves as if they were gods. From the perspective of what God has done, so many songs of praise abound, for example: (a) Tubara Ya mmamma. Si Ya na O meela. Onye huru Jisos tubara Ya mmamma si Ya na O meela (Bless him, tell him that he has done well, whoever sees Jesus should bless him and tell him that he has done so well), (b) Kpo Ya omemma (3x) omemma, Kpo Ya omemma, Omemma, E – – omemma, E – – omemma, omemma,omemma (Call him the Doer of good), (c) O Lord I am very very grateful, for all you have done for me. O Lord I am very very grateful, I am saying thank you my Lord, (d) Mkpo aha ya, ihe ukwu ga-eme, Mkpo aha ya, ihe ukwu ga-eme (If I call his name great things will happen) (e) Na so so wonder Jesus dey do, Na so so wonder Jesus dey do, Eee He has done it for me (thrice), Na so so wonder Jesus dey do (Jesus performs so many wonders, Yes He has done it for me). All the songs cited above focus on the good deeds or wonders of God. They express a conviction about what God has done, can do and is doing in the present moment. WORSHIP SONGS Worship is really an intimate encounter between a human person and the Creator. Therefore, worship song can be defined as one that involves “one’s heart expression of love, adoration and praise to God with an attitude and acknowledgement of his supremacy and Lordship.” It is an outpouring in song, with “awesome wonder and overpowering love”, of one’s “inner self upon the Lord Jesus Christ in affectionate devotion” (Sorge 2001, p. 64). Furthermore, Bob Sorge (cf. 2001, pp. 68-71), an expert of Pentecostal/charismatic worship, describes worship song as requiring a relationship of communion or fellowship “because worship is a two-way street, involving giving and receiving.” He also sees worship songs as a bit “more reflective and quieter,” requiring less bodily and spiritual effort than praise and characterized, as it were, “by a quiet and unassumed basking in God’s presence” (Redman 2002, pp. 37-38). Worship songs often give rise to an experience of altered states of consciousness or ecstasy.1 Altered states of consciousness can be seen as a psychosomatic mode in which the human person is open to the irruption of his or her sensibility by the numinous power and presence of the Holy Spirit. With this irruption, one begins to have “decreased awareness of one’s surrounding [as well as] a decreased sense of control” (Magliocco 2004, p. 160; See Evans 1979, pp. 33-48 and Sturm 2000). I argue that this is one of the ways by which Nigerians take flight from the raw reality of social upheavals facing them due to the political mismanagement of the country by the political class. Songs that are used for worship includes the following (a) Thou art worthy, thou art worthy O Lord to receive glory honor and power, for thou has created all things and for thy pleasure they are and were created (b) Holy, holy,holy,holy, Lord God almighty, as we lift up our hearts before you as a token of our love, holy, holy, holy, holy and (c) You are highly lifted up, there is no one like you, Halle, Halle, Halleluia. SPIRITUAL WARFARE SONG In Nigerian Pentecostalism/Charismatism, evil forces are seen as expressions of satanic power. Indeed “belief in invisible spiritual forces, especially malevolent spiritual powers” is a pivotal aspect of indigenous African religious worldviews and this cosmic perspective is deeply embedded in both the credo and praxis of African Christianity (Ray 1993, p. 268). Nigerians conceive evil not in mere moral or abstract way but “in terms of real powers such as witches and spirits” (Probst 1989, p. 482). Hence, the necessity of waging constant spiritual battle against the evil and malevolent forces. A Nigerian research respondent, Tony Chukwu, told me that spiritual warfare has to do with “spiritual battle against the enemies, the principalities and power” (Interview 5/25/2013). Note that these principalities and powers can in fact be conceived as operating within the political arena, what with the common belief in Nigeria that many politicians and power brokers are members of satanic cults! Warfare songs are therefore meant to deal with all situations of direct or indirect satanic oppression, whether this oppression is understood in a vague and general way or in a particular concrete case of individual diabolical harassment. Warfare song therefore becomes a way of “reaching out to the power of the spirit in battling against the physical and social afflictions of daily life” (Butticci 2013, p. 7). Some good example of warfare chants are: O bu onye na-ebu agha, okpara Chineke na-ebu agha, agha. UmuChineke agha adawo, umu Chineke na agha dara, agha, umu Chineke agha adawo agha. O bu onye na-ebu agha, agha (Who wages the battle, the Son of God wages the battle, children of God there is war, children of God there is war, who wages the battle). Another good example is the song: “When Jesus says ‘yes’ nobody can say ‘no.’” There is also the popular Nigerian Pidgin English song: Satan don fall for ground-o, macham macham.(Satan has fallen to the ground, march on him, march on him). SINGING AS AN INSTRUMENT OF RESISTANCE With the foregoing, it is clear that gospel chorus singing in Nigerian churches is not just only an element of worship and Christian religious practice but are instruments of social resistance. Social resistance in this case is not to be understood in terms of physical or violent response to the muddied socio-political status quo but a way of internal or attitudinal negotiation or/and renegotiation of one’s relationship to the various issues that are connected with the political malaise of Nigeria as a nation. At the first level, these gospel choruses constitute a refusal to yield to the onslaught of the demonic that is believed to be afflicting Nigeria. Many Nigerians are strongly convinced that the negative trajectory of the country reached its climax with the organization and execution of the Nigerian Festival of Art and Culture (FESTAC) in 1977. With its profligate waste of money, lavish showcasing of nudity-prone cultural performances and outright idolatry, the FESTAC heralded “the beginning of Nigeria’s downward trend in every sphere of life,” inasmuch as by the festival, “Nigeria had given an open invitation to the very Kingdom of the Devil to invade her and perpetuate his reign of terror” (Ononyemu 1993 quoted in Hackett 1998, p. 261). With this kind of belief system, Nigerians’ adoption of gospel choruses – especially the spiritual warfare songs – can arguably be seen as an act of saying “NO” to the prospect of domination by the devil in any aspect of their life. A practical parallel to this negation can easily be seen in the contemporary efforts being made in various enclaves of Igboland to rid “the land” of evil luck bringing idols. At the next level, Nigerians are telling the political class: “we don’t give a damn about what your stinking greed can do to us. With God we can make it.” Nigerians are not so naïve as to be ignorant of what they suffer from the political class. Indeed, it would even seem that the political class is aware of Nigerians’ almost unbreakable resilience and their willingness to bear being exploited. The whole scenario is further helped or accentuated by the reality of what one would regard as the “do you feed me?” Nigerian mentality. This is where the song “Me I no go suffer…” falls in. Nigerians do not see God as a Deus otiosus – a far away God. He is always near and is immediately interested in their affairs. Political stalwarts may fail them but God will never fail them. Hackett notes about the Pentecostal churches in Nigeria that “their progressive, goal-oriented attitudes attract the youth, disillusioned with the empty moral claims of their elders and leaders” (Hackett 1998:260). These attitudes found their way to the youths as subtle messages distilled through the gospel choruses such as “Me I no go suffer…” and “Why I no go make inyanga.” Finally, Nigerians see the very problems facing them as mountains that must be removed. Consider the song: “it’s not by might (2 times), it’s not by power (2 times), by my Spirit says the Lord, this mountain shall be removed (3 times) by my Spirit says the Lord.” In this song, one sees Nigerians’ refusal to be mastered or broken by the spates of fuel scarcity that is now becoming history with the deregulation, endless news of corruption in high places, the rising price of the dollar and household goods in the market. As if to show off that they can always thrive amidst hardship, Nigerians will proudly sing: People dey ask me say, wetin dey make you fine, I just dey tell them say: Na Jesus dey make me fine. Thus, in spite of hardships in Nigeria, marriage celebration keeps being a free-for-all carnival-like fanfare; funerals remain a wild “celebration of life” while December period has not ceased being a time of opening of new houses, showcasing of new cars and other similar celebrations that serve as evidence of “good living.” CONCLUSION Nigerians love singing. Indeed, my research about singing in Nigerian churches reveals that Nigerians cannot conceive a church service without vibrant singing and energetic rhythmic movements of their bodies. Call it dancing, if you like! But one needs to notice that apart from the spiritual significance of these songs, they constitute subtle instruments of social but internal resistance by which Nigerians are able to come to terms with their daily hardships as citizens of one of the most corrupt nations on earth where, in spite of unending abundance of natural resources, ordinary Nigerians in the street continue to suffer endlessly while some of their political leaders continue to batten on spoils of their political office. I argue that Nigerians are not likely ready and probably will never be ready for any war – and war is, of course, not a good course to take. Nor are they likely ready for any seriously violent revolution in the guise of the Arab spring against their politicians, for that matter – and I do not pray for this either. However, the undeniable phenomenological reality on the ground is that they never place and have never placed much trust on the political class. Their confidence is only in the God of miracles, whom they praise in songs from day to day – and they listen to hundreds of praise and worship songs that keep being produced from week to week in Nigeria. This God – they believe – really so takes care of them that in him they can even make inyanga for the political class. In him, and only in him, they dey kampe. And the case remains closed. ENDNOTE 1. Scientifically defined, ecstasy is a “qualitative alteration in the overall pattern of mental functioning, such that the experiencer feels his [sic] consciousness is radically different from the ‘normal’ way it functions” (Tart, 1972:94 quoted in Magliocco 2004:160). BIBLIOGRAPHY Butticci, A. (2013). Introduction. Na God: Aesthetics of African Charismatic Power, ed. by idem. Padova, Italy: GraficheTuratoEdizioni: 6-10. Evans, H. (1979). Alternate States of Consciousness. Wellingborough, U.K.: Thorson’s Publishing. Hackett, R. I. J. (1998). Charismatic/Pentecostal Appropriation of Media Technologies in Nigeria and Ghana. Journal of Religion in Africa, Vol. 28, Fasc. 3, 258-277. URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1581571 Harvey, T. (2008). Narrative Theology. Global Dictionary of Theology: A Resource for the Worldwide Church, ed. by William A. Dyrness and Veli-Matti Kärkkäinen. USA: InterVarsity Christian Fellowship: 598-602. Liesch, B. (1996). The New Worship: Straight Talk on Music and the Church. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker. Magliocco, S. (2004). Witching Culture: Folklore and Neo-Paganism in America. Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press. Phenomenology Represents an ‘Intellectual Charity,’ Says John Paul II. Zenit Innovative Media, Inc. http://www.zenit.org/article-6866?l=english. Probst, P. (1989). The Letter and the Spirit: Literacy and Religious Authority in the History of the Aladura Movement in Western Nigeria.” Journal of the International African Institute, Vol. 59, No. 4, pp. 478-495. URL: http:// www.jstor.org/stable/1159943. Ray, B. C. (1993). Aladura Christianity: A Yoruba Religion. Journal of Religion in Africa, Vol. 23, Fasc. 3: pp. 266-291 URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1581109. Redman, R. (2002). The Great Worship Awakening. San Francisco: John Wiley and Sons Inc. Schutz, A. (1971a). Making Music Together: A Study in Social Relationship. Collected Papers II: Studies in Social Theory. TheHague: Martinus Nijhoff: 159-178. _____. (1979b). Mozart and the Philosophers. Collected Papers II: Studies in Social Theory, ed. & intro. by Arvid Broderson. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff: 179-200. Sorge, B. (2001). Exploring Worship: A Practical Guide to Praise and Worship. Missouri: Oasis House. Stone, R. M. (2008). Theory for Ethnomusicology. New Jersey: Pearson Education Inc. Sturm, B. W. (2000). The ‘Storylistening’ Trance Experience. Journal of American Folklore 113, no. 449: 287-304. Tart, C. T. (1972). Scientific Foundations for the Study of Altered States of Consciousness. Journal of Transpersonal Psychology 18, 93-124. Titon, J. T. (2008). Knowing Fieldwork. In Shadows in the Field: New Perspectives for Fieldwork in Ethnomusicology, edited by G. F. Barz & T. J. Cooley. Oxford: Oxford University Press: 25‐41. |

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||