Global Online Journal of Academic Research (GOJAR), Vol. 3, No. 2, April 2024. https://klamidas.com/gojar-v3n2-2024-03/ |

|||||||||||

|

Counterterrorism and Counterinsurgency and Socio-Economic Development in Nigeria By Livinus Nwaugha

Abstract Peace and security are required for sustainable socio-economic development of any country; in some parts of Nigeria, these are disrupted by terrorist and insurgent activities, hence the Nigerian government’s long-drawn deployment of its military in counterterrorism and counterinsurgency operations. The military is saddled with the task of combating armed groups, such as the Boko Haram insurgents in the north-eastern part of the country and Niger Delta militants, among many others engaged in criminal activities that threaten the security of lives and properties and sabotage economic activities. Most of the previous studies conducted on the nature and operations of the terrorist groups and insurgencies in Nigeria have focused on their atrocities and their disruptive impact on society. This study reviews the various aspects of the crisis with a view to highlighting how the protracted counterterrorism and counterinsurgency offensives have resulted in diversion of public funds and gulped up huge resources that could have been used for the socio-economic development of the country. Based on available data, the study concludes that although fighting terrorism and insurgency is a necessary duty, the corruptive and ineffective manner in which it has been done in Nigeria has further aggravated the plight of the people and impeded socio-economic development. Keywords: counterterrorism, counterinsurgency, Nigeria, threats, socio-economic development Introduction Socio-economic development and a peaceful and stable polity are prerequisites for the attainment of prosperity in any country, and these fundamental requirements are threatened in many countries by violence unleashed by terrorists and insurgents. This is why, wherever there is a prevalence of terrorism and insurgency, states have adopted several strategies to deal with the menace. As Nigeria’s experience has shown, attacks by terrorist and insurgent groups are generally unconventional in nature and are highly unpredictable. Diverse approaches are required to deal with the problem, particularly where the operations of the group spill over national borders or form alliances with international terrorist organizations. Terrorism and insurgency appear to have assumed greater global dimension since the end of the Cold War in the late 1990s (William, S. Lind et al, 2008) but it was the September 11, 2001 terrorist attack at New York’s World Trade Centre that reinforced the utmost importance of counterterrorist and counterinsurgent operations (Gingell, 2021). That attack, in which 2,996 people lost their lives (Washington Post, 2013), was preceded by the 1993 World Trade Centre bombing. In Nigeria, militant groups in the Niger Delta and the Boko Haram insurgency in the north-eastern part of the country, among others, currently pose serious security threats. According to a 2024 figure released by the Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect, “more than 35,000 people are estimated to have been killed as a result of Boko Haram attacks between 2009 and 2020”. Thousands of people have also been killed by other insurgent groups operating in the northeast, such as ISIS-WA and Ansaru. All of these, and the fact that conventional military strategies are often ineffective in dealing with terrorists, have led to the formation of counterterrorism (CT) and counterinsurgency (COIN) joint taskforces in Nigeria and elsewhere in the world. The faceless, multi-faceted and international nature of many terrorist and insurgent operations makes inter-agency collaboration crucial and also necessitates international partnerships and cooperation. The cost implication of countering the atrocities of terrorist and insurgent groups, and of managing the human, economic and environmental emergencies caused by them is enormous, and has in no small measure affected the socio-economic development of not only the affected areas but of the country as a whole. Objective and Methodology of the Study Diverse studies have been conducted on the nature, operations, and negative impact of the terrorist groups and insurgencies in Nigeria. Each of these studies mostly focused on some dimension of the problems – such as disruption of communal life, violence, kidnapping, human rights violation, forced recruitment and banditry – caused by these gangs and the Nigerian military’s war against them. The current study reviews the various aspects of the crisis with a view to highlighting how the protracted counterterrorism and counterinsurgency offensives against terrorist and dissident groups have gulped up huge resources that could have been used for the socio-economic development of the country and how failure by the Nigerian government to quickly and roundly win the war against terror could further stunt Nigeria’s stability and economic growth. The methodology adopted for this study was secondary source of data collection, as it provided a convenient and broad-based access to the mass of information needed for a holistic view of terrorism and insurgency in Nigeria and the operations being conducted by the military to counter their massive disruption of social life and economic activities. Data-collection sources utilized in this study included news reports, books, previous research conducted on the topic, and authoritative websites that captured and recorded the activities of insurgents and terrorists in Nigeria. Data collected were subjected to qualitative analysis to arrive at the findings and conclusion of the study. Definition of Key Terms The key terms of this study that need to be defined in order to understand the issues discussed are terrorism, insurgency, counterterrorism, and counterinsurgency. Not all terror is terrorism and not all forms of militant agitation can be termed insurgency. Terrorism and insurgency have assumed global dimensions and so a generally-acceptable definition is required to aid our understanding of the nature of each of these terms and why both forms of militant oppression should be countered and censored by every orderly and democratic society as well as by the international community. Although there are different definitions of terrorism, some of them ideologically motivated, this study’s use of the term would be based on two standard definitions quoted by Gingell (2021) that defined terrorism as “premeditated, politically motivated violence perpetrated against non-combatant targets” and as “the unlawful use of force and violence against persons or property to intimidate or coerce a government, the civilian population, or any segment thereof, in furtherance of political or social objectives”. While “insurgency” as a term may share all or some of these attributes, it is different from “terrorism” in the sense that it is targeted at gaining control of a territory and its resources. This is why the US Department of Homeland Security defined insurgency as a “protracted political-military struggle directed towards subverting or displacing the legitimacy of a constituted government or occupying power and completely or partially controlling the resources of a territory through the use of irregular military forces and illegal political organizations” (Gingell, 2021). Counterterrorism and counterinsurgency, therefore, are approaches and operations geared towards opposing, responding to and counteracting terrorism and insurgency. These approaches may be enemy-centric, population-centric or authoritarian-centric (Bala & Tar, 2019). Scott (2007) described counterterrorism and counterinsurgency as the totality of political, economic, social and security measures put in place to end armed violence while promoting political stability. Scott, however, like most commentators, offered no suggestion on how to end violent agitation where injustice, mounting unemployment and marginalization are the order of the day in a country so blessed in natural and human resources, such as Nigeria. Theoretical Framework The theoretical framework adopted by this study to explore the issue of counterterrorism and counterinsurgency and their impact on socio-economic development in Nigeria consists of Maslow’s needs theory, and related peace-enhancing viewpoints, and Todaro’s development theory. Maslow’s Needs Theory and Related Concepts Maslow’s needs theory and similar viewpoints generally affirm that humans have certain needs and that when these needs are not met, they would create feelings of frustration and anger. However, as diverse as human needs are, there is no time they would all be met, as they are ever evolving. The endless nature of human needs makes it difficult to reach a point where human beings would cease to have needs. The insatiability of human needs make conflict inevitable. This is because human needs vary from basic or essential needs to complex personal or group desires that change as human beings and societies develop or evolve. Though human needs are not static but dynamic, there are certain basic things universally needed by all human beings for their survival and wellbeing. They are food, water, clothing, shelter, security and justice; when these are absent, they may trigger terrorist or insurgent activities. There are different needs theories but, generally, they make the following assumptions:

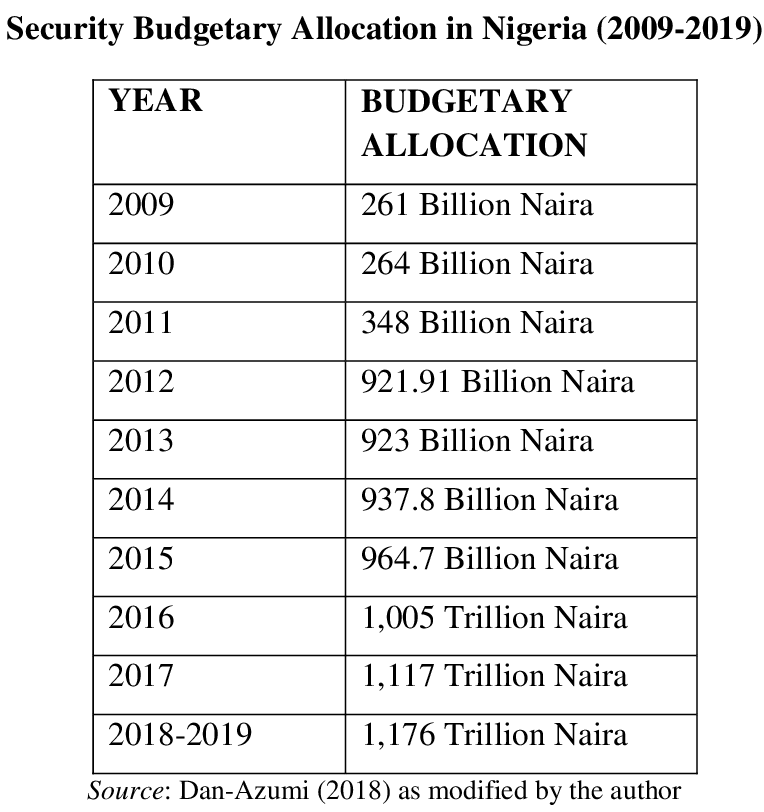

As Maslow’s hierarchy of needs extrapolates, human needs are highly insatiable: as soon as one need is met, another need arises. Maslow’s pyramid of needs categorises needs in terms of their order of importance, beginning with basic needs, such as food, shelter and clothing, to essential needs, such as the need for self-actualization and self-fulfillment (Maslow, 1973). Danesh (2006) sees the issue of justice as a fundamental human need. For him, the matter of distributive justice is a primary human need for lack of it usually leads to series of agitations and conflicts, especially in countries and communities where social exclusion is the rule rather than the exception. Some people believe that unrealised justice and inclusion needs are the root causes of terrorism and insurgency, as inability to meet these needs lead to frustration and anger. Hertnon (2005), in his categorization of needs, places survival and betterment needs as the most basic universal needs individuals and groups do not play with, as any action or inaction which tends to undermine these basic needs may lead to violence. Critics of these needs theories opine that since human needs change over time, it is difficult to ascertain which needs are so important that failure to meet them would lead to violent conflicts. They argue that it is only when needs are static that their evaluation and analysis can be carried out in relation to prevailing circumstances. These criticisms notwithstanding, the needs theories offer valuable insight into wide scale occurrence of terrorism and insurgency in Nigeria and, probably, elsewhere in the world. Todaro’s Development Theory Todaro’s development theory and similar theories are relevant frameworks in this study because some people are of the view that the root cause of terrorism and insurgency in Nigeria is lack of socio-economic development. Although the concept of development has evolved over time, it still constitutes a significant benchmark by which the progress of any country is measured. Due to its fluid nature and various usages over time, it is now rather difficult to come up with a concise meaning of development, more so because the concept appears virtually in all disciplines with different meanings. However, development on a general note connotes an elevation of people’s life towards a better condition (Egonmwan & Ibodje, 2001). The fact that the things that constitute better life vary in accordance with people’s needs and expectations means that there is no one-size-fits-all definition of development, as it is an on-going phenomenon (Adetula, 2013:308). However, according to Todaro (1981): Development must represent the entire gamut or change by which an entire social system tuned to the diverse needs and desire of individuals and social group within that system move away from a condition of life widely perceived as unsatisfactory and toward a situation or condition of life regarded as materially and spiritually better (Todaro, 1981:70). Development, pertaining to self-esteem, refers to an individual’s degree of self-respect, accommodation and tolerance (Todaro, 1981:71). In the view of Goulet (1992), development is a multidimensional concept which can be seen in three areas. They are life sustenance, self-esteem and freedom. At these three levels what constitute development varies from food, shelter to protection. The extent to which these attributes are available in a society determines its level of development. Basically, what causes some level of dissatisfaction is when people are uncertain about when the next meal would be available, and when their protection is uncertain or in abeyance. These values mark how advanced people are. Where there is incessant altercation and infighting development would be elusive, but at times these altercations drive development; this is why Goulet (1992) generalizes that development is a two-edged sword which can be used to build or to destroy. According to Egonmwan & Ibodje (2001), the whole essence of development is to eradicate poverty through the enhancement of the living condition of the people. At various times, since Nigeria’s independence in 1960, several conscious steps have been taken to chart the nation’s development. Immediately after independence, a five-year development plan (1960-65) was drawn to drive the country’s development. From 1970 to the 1980s, several developmental steps were taken; but towards the mid 1980s onwards, due to maladministration and corruption, the nation was plunged into economic mess which culminated in its adoption of structural adjustment programme (SAP) in 1986. The period of the 1970s registered appreciable development indicators both in savings and purchasing power with the naira being stronger than the US dollar, but beyond this period a general distortion characterized the entire system. As Ayorinde and Uga (1999) captured succinctly, “the tapping of the country’s endowment of various resources has not culminated in improved living condition for the majority of the people”. By 2001, during the presentation of the appropriation bill to the National Assembly, President Olusegun Obasanjo was emphatic when he said publicly that Nigerians have not sufficiently improved since its hard-won democracy (Taiwo, 2001). Improvement must be judged by the welfare of the people, not by mere statistics; the questions to be asked, according to Sear (1969), are: What has been happening to poverty? What has been happening to unemployment? What has been happening to inequality? If all three of these have declined from high levels, then beyond doubt this has been a period of development for the country concerned. If one or two of these central problems have been going worse, especially if all three exists, it would be strange to call the result development even if per-capita income doubled (Seer.1969:3). Counterterrorism and Counterinsurgency: the Nigerian Experience Since the return of democratic rule in Nigeria in 1999, and its accompanying cry of marginalization, sectional politics, mounting unemployment and increasing poverty in the midst of plenty, terrorism and insurgency and related activities have continued to hinder the provision of social goods to the citizenry. This necessitated the formation of civilian and military joint task forces (Hamza & Sawab, 2013; Bala & Tar, 2019) to deal with the problem. In Nigeria, counterterrorism and counterinsurgency has borne different names – from Operation Restore Order (ORO) 1, 2, and 3, Operation Zaman Lafiya, Operation Python Dance, Operation Lafiya Dole, to Operation Thunder Strike, to mention but a few. The combative nature of most of these names reflects the operatives’ awareness of the heavy arms and ammunitions at the disposal of the terrorists and insurgents and the danger they pose to the socio-economic development of the Nigerian state. In an atmosphere where life has become “short and brutish”, no visible and calculated development can thrive. Since it is their constitutional mandate to quell insurrection of any kind and restore socio-economic activity, the military swung into action to counter the terrorists and insurgents in collaboration with civilians in the affected communities. The local communities, using an assortment of local weapons such as knives, swords, dane-guns, bows and arrows (Olugbode, 2013; Bala & Tar, 2019), formed vigilante groups to enhance their fight against violent-non-state actors (VNSAs). The use of vigilante groups is very old and predates Nigeria’s independence in 1960 (ICG, 2022:6). Before independence, vigilante groups constituted the vanguard of the communities that protected and secured lives and properties. Mainly able-bodied men, grouped according the age, constituted these groups. Most essentially, vigilante groups provided security for the local communities; in some cases, where there were conflicts amongst communities, the vigilante group mediated to enthrone peace. When there are conflicts of roles and functions amongst the vigilante groups, it is settled by the traditional authority of their community (Ogbezor, 2016:1). Arguably, the vigilante groups also played important roles in the provision of socio-economic goods, especially as they constituted the work groups that cleared, planted and harvested crops. Moreover, they ensued that justice was maintained in their communities. In recent times, especially since 2000, vigilante groups have been integrated into the mainstream of counterterrorism and counterinsurgency operations in Nigeria, largely due to the overwhelming of the mainstream security architecture by the terrorists and insurgents who use their better understanding of their local terrain to inflict incalculable damage on the military operatives. By 2000, the number of vigilante groups in Nigeria has greatly increased; they bear different code names, such as Niger State People Congress (NSPC) in Niger State, Neighborhood Security Committee (NSC) in Akwa Ibom State, Edo Vigilante Service (EVS) in Edo State, Hasbah Corps in Kano State, Yan-Sakai in Katsina State, Yan Komiti in Bauchi State, Amotikun in the southwestern zone, and Ebubeagu, which was formed by the State Governors of the southeastern zone of Nigeria. The synergy between the civilian taskforce and military force became necessary owing to the fact that members of vigilante groups are versed in the knowledge of their rural areas where the insurgents and terrorists operate. It is necessary to make this explanation or clarification here. Terrorism and insurgency are not limited to local or rural areas as their activities have equally been registered in major cities and towns in Nigeria, including Abuja, Nigeria’s capital, Owerri, the capital of Imo state, Makurdi in Benue state, Jos in Plateau state, Katsina in Katisna state, Maiduguri in Borno State, Minna and Suleja in Niger state, and Damaturu in Yobe State. There are misgivings in some quarters that the synergy between the civilian and military operatives is a mere marriage of convenience, and that the military has always treated the civilian populace with disdain whenever it suits them. Bala and Tar (2019) assert that for counterinsurgency operation to be effective and possible the local populace should be separated from the insurgents and terrorists. There are records of incidents where the military joint taskforce left the insurgents to attack the local communities, accusing them of shielding the insurgents and the terrorists. The military joint taskforce has also been accused of unlawful arrests, extra-judicial killings, rape, looting and destruction of properties belonging to some communities. This is why some scholars assert that counterterrorism and counterinsurgency operations in Nigeria are politically motivated and aimed at disintegrating the already disenchanted local communities. Amnesty International, in a report cited in Omilusi (2016), said the military were better trained and equipped to enforce counterinsurgency and counterterrorism, and need not integrate the civilian populace so as to reduce the number of casualties. Transparency International has described Nigerian counterterrorism and counterinsurgency military operatives as barbaric, especially after their 6th of January, 2019 activities at the offices of the Daily Trust Newspaper in Maiduguri and Abuja. Some people are of the opinion that terrorists and insurgents have infiltrated into the corridors of power, and some terrorists and insurgents have even openly named the Nigerian government as their major sponsors. In this regard, the late General Sani Abacha is reported to have said that terrorism and insurgency cannot last 24 hours if the hands of government are not in it. The case of Boko Haram appears to support this claim. According to Shehu (2024), Boko Haram was formed in 2002 and assumed a terrorist dimension in 2009; but it took nearly five years (2014) for the government to proscribe it and to declare it a terrorist organization. All these agitate the minds of Nigerians who find it difficult to understand why the war against terrorism and insurgency in Nigeria, after so many years, is yet to be won. How Counterterrorism and Counterinsurgency Undermine Socio- Economic Development in Nigeria Bala and Tar (2019) see counterterrorism and counterinsurgency as veritable moves needed for the restoration of normalcy so that socio-economic development can thrive. This study, however, considers many aspects of Nigeria’s counterterrorism and counterinsurgency initiative as a drain on the country’s resources, especially given the fact that the nation has not seen the end of terrorism and insurgency after so much has been spent on countering them. Apparently, a lot of the money has been diverted. For instance, former National Security Adviser (NSO) to President Goodluck Jonathan, Col. Sambo Dasuki, was alleged to have embezzled 2 billion US dollars, money that would have been used to fight terrorism and insurgency. Till date, nothing more is heard about that case. According to Usman (2024), “The military is deployed virtually to every part of the country in order to bring respite at great cost to the country, including misappropriation of colossal amounts of funds voted for logistics and personnel welfare”. A table of Nigeria’s security budgetary allocation (2009 to 2019) is presented below, as it would help us to understand the “colossal” nature of spending on security in the country.

The statistics above buttress our argument that counterterrorism and counterinsurgency operations in the country have depleted the nation’s resources, without overwhelming the militants and creating an atmosphere conducive for the socio-economic development of Nigeria. As at 2012 when the security budgetary allocation was 921.91 billion naira, unemployment rate was 30.30% and in 2015, when the security budgetary allocation rose to 964.7 billion naira, the unemployment rate was 38.38% while the poverty rate was 76.3%. In 2017, when the security budgetary allocation was 1117 trillion naira, the rate of unemployment was 43.34% while poverty rate was 74.70% (Dan-Azumi, 2018). Life expectancy in Nigeria was 52.40 in 2014, 52.84 in 2015, 53.29 in 2016, 53.73 in 2017, 54.18 in 2918, and 54.49 in 2019. As noted by UNICEF (2018), in 2015 37% of Nigeria’s health facilities were closed down while 40% and 44% were closed down in 2017 and 2018 respectively. Conclusion Having examined counterterrorism and counterinsurgency in the context of ending terrorism and insurgency in Nigeria to facilitate socio-economic development, the findings of this study indicate that both operations have, instead, hindered socio-economic development. While acknowledging the necessity of countering terrorism and insurgency, this paper notes that the corruptive and ineffective manner in which this has been done in Nigeria has further aggravated the plight of the people, as resources which could have been used to alleviate the sufferings of the masses were unaccountably poured into the operations while other critical areas of social and economic concern were starved of funds. References Adetula, V.A.O. (November-December, 2012). Expanding Women’s Option for Effective Political Participation in Nigeria; Nigerian Forum. A Journal of Opinion on World Affairs, Vol.33 No 11-12, 364-374. Ayorinde, F.O and Uga. (1999). Resource Mobilization and Management in African Country: The case of Nigeria in Fajingbesi, A. et al (ed) Resource Mobilization and Management for Development. NCEMA, Ibadan. Bala, B. & Tar, U. A. (2019). Insurgency And Counterinsurgency In Nigeria: Perspective On Nigerian Army Operation Against Boko Haram. Nigerian Defense Academy Press. Egonmwan, J.A. & Ibodji, S.W.E. (2001). Developing Administration: Theory and Practice. Resyin Nig Co. Ltd, Benin City. Gingell, Thomas. (Spring 2021). Counterinsurgency and Counterterrorism: the Replicability of Best Practice. Undergraduate Journal of Political Science, 5(1), 123-139. Goulet, D. (Fall, 1992). Development Indicators: A Research Problem, A Policy Problem. The Journal of Socio-Economic Research, 21:3, 245-269. Hamza, I. & Sawab, I. (2013). Civilian JTF Hunts Boko Haram in Borno, Daily Trust, Nigeria. Hertnon, S. (2005). http://universal/humane.wordpress.com/ relevant-research/simon-human-needs/ Accessed Decem ber 2022. http://www.globalr2p.org/countries/nigeria/#:~:text=In%202015%2 0the%20African%20Union,attacks%20between%202009%20 and%202020. Mashow A.H. The Farther Reaches of Human Nature: Harmonds Work U.K: Penguin Book 1973 New World Encydopedia. http://www.newworldencydopedia.org/entryconflicttheory. Accessed December,2009 Olugbode, M. (2013). Civilian JTF: A Brewing Disaster Nipping in the Bud. ThisDay, Nigeria. Omulusi, M. (2016). Insurgency and Terrorism in Nigeria, Perspectives, Phases and Consequences. Olugbenga Press and Publishers, Ado-Ekiti. Plumer, B. (September 11, 2013). Nine facts about terrorism in the United States since 9/11. The Washington Post. https:www. washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2013/09/11/nine-facts-about-terrorism-in-the-unite d-states-since-911 Scott, R.M. (2007). The Basics of Counterinsurgency. Small War Journal. Retrieved 7 November 2022 from http:/www.Small war journal.com/document/moorcom paper. pdf. Sear, D. (1969). The Meaning of Development. Eleventh World Conference of the Society for International Development, New York Pantheon. Shehu, A.Y. (2024). Boko Haram and Other Security Challenges in Nigeria. National Open University of Nigeria, Abuja. Taiwo, I .O. (2001). Review and Appraisal of the year 2000 Federal Government Budget Performance. A Paper Presented at the CBN/NES Seminar on the 2001 Federal Government, Lagos January 25 Todaro, M. (1981). The Economic Development in the Third World (2nd ed). London, Longman. UNICEF (2018). Wash as a Cornerstone for Conquering the 2017 Cholera Outbreak in Borno State, North-East. Usman, B. (2024). Review of the book Boko Haram and Other Security Challenges in Nigeria presented at the Shehu Musa Yar’adua Conference Centre, Abuja, on April 19, 2024. William, S.L, Keith, N., John, F.S., Joseph, W.S. & Gary, I.W. (2008) The Changing Face of War: Into the Fourth Generation. Routledge, New York.

|

|||||||||||