|

|

Journal of Education, Humanities, Management and Social Sciences (JEHMSS), Vol. 2, No. 2, March 2024. https://klamidas.com/jehmss-v2n2-2024-03/ |

||||||||||

|

Parameters for Determining Core Cultural Symbols: A Philosophical Analysis Innocent Ngangah ABSTRACT There is need to work towards the identification of common parameters for determining core cultural symbols in philosophy of ethnic studies and other forms of cultural research. This has become cogent since scholars are increasingly utilizing the concept of symbolic transformation in various studies of cultural groups and identities. In such studies, symbols are treated as mental representations of cultural ideas, objects or realities. Within this context, core symbols are those symbols which represent the central cultural beliefs of a cultural group, be it racial, ethnic or any other group. This paper would attempt to identify parameters which would guide the cultural researcher through the intricacies of identifying a cultural group’s core symbols. This is important because a given cultural group’s core values and cultural systems can only be discerned and grasped through the recognition of its core symbolic logic. Keywords: signs, symbolic transformation, traditional African society, cultural philosophy 1. Introduction While the study of the culture of ethnic groups by foreign anthropologists, ethnologists and philosophers has waned, academic research on the culture of ethnic groups by scholars from those groups is believed to have risen globally. The “Humanities Indicator”, an index of the American Academy of Arts and Science, for instance, shows that in 2014, “traditionally underrepresented racial/ethnic minorities received 17.0% of all bachelor’s degrees in philosophy (Indicator II-50a)”, an increase of “eight percentage points from 1995 (the first year for which data of this kind are available)”. At the Masters level, these minorities “earned 10.2% of philosophy degrees awarded in 2014, up from 6.5% in 1995 (Indicator II-50b)” while at the PhD level, they “reached a high of 7.9%, a level nearly three times as great as that observed in 1995 (Indicator II-50c)”. Both philosophy and their cultural backgrounds must have mutually benefited from these students’ researches. And in Africa, where the primary research for this paper was conducted, there is hardly any philosophy department of any university that does not offer courses in African philosophy. At their basic level, cultural studies, including philosophical ones, are narrations about how culture and mind are related through symbols (Wagoner 2009). So, a clear understanding of what “culture” and “symbols” are, especially in the context of this study, is crucial to our appreciation of the necessity of setting parameters for determining core cultural symbols. We will explain what we mean by “culture” and “symbol” in subsequent sections of this paper which uses the culture and symbols of the Igbo people of south-eastern Nigeria to illustrate the heuristic role universal parameters can play in identifying any given group’s core cultural symbols. The paper is in six sections, namely, the introduction, which states the importance of the topic within a backdrop of growing interest in the philosophy of cultural groups; cultural essence, a section devoted to explaining the meaning of “culture” as used in this study; signs and symbols – what they mean and the differences between them; core symbols – their relevance in mapping the core areas of any group’s culture; parameters for identifying core symbols – a set of theoretical rules and an illustration of how they can be applied; and conclusion. 2. Cultural Essence What sets a social group apart in terms of its worldview, social organization, and ways of carrying out social functions or activities is what we call culture. Culture, therefore, accounts for a given group’s philosophy of life, ideas about existence, social relationships, work ethic, and ways of conducting transitional ceremonies (such as those associated with birth, marriage, and death) and religious rituals. Culture, in determining and enforcing veritable values in a society, enables it to avert social chaos and disintegration. As reference.com puts it, “Society could not function without cultural norms that assist in governing behavior and values, and culture could not exist without societal influences to create it.” Culture is the traditional beliefs and practices of a society or a group of people within a society. In this sense, culture is synonymous with tradition, customs, heritage, and mores. Extending the meaning of culture even further, Adian and Arivia (1974) say that: Culture refers to the cumulative deposit of knowledge, experience, beliefs, values, attitudes, meanings, hierarchies, religion, notions of time, roles, spatial relations, concepts of the universe, and material objects and possessions acquired by a group of people in the course of generations through individual and group striving. For us, here, culture consists of a cultural group’s beliefs, values, norms, language, attitudes, activities, ceremonies, and objects and the unique way of life which these entail or reflect. Hence, culture provides the social platform and points of reference within which a given group organizes, interprets and makes sense of their internal and external environment. In short, culture is the traditional system around which a society is organized and by which its guiding perspectives and practices are carried on from one generation to another, and this often dates back to ancestral times. In many societies, culture is conveyed and sustained by oral tradition. A distinct social group, such as an ethnic or racial group, owes its uniqueness to a shared cultural identity founded on shared cultural values. And cultural identities can be socially and psychologically stabilizing for groups and individuals. Absence of such identities can be very disorienting and is known to have been the root of deviant, counter-productive and socially divisive behaviour. Such behaviour is experienced usually in those societies where the authentic culture has been supplanted by counter-cultural forces that violate a people’s definition of who they are and how they customarily do things. It is generally agreed that culture is not an inborn trait but something that individuals and groups can learn. In other words, cultural traits are not innate but rather learned acquisition of a socially-integrating set of thoughts and actions as they were received or changed by previous generations via oral tradition. Such changes are not formal amendments and rarely constitute a total break with the past. More often than not, they are little departures from past attitudes and practices or merely generational adjustments that delicately tinker with the meaning and manner of a people’s cultural references and habits. So, although culture is a continuum authenticated by roots in the distant past, it is at the same time intrinsically dynamic. In whatever form culture is manifested, symbols play a very key role in enabling it to generate meaning for members of a given cultural group. 3. Signs and Symbols Having explained what we mean by “culture”, we now turn to “symbol”. Generally, a symbol is something that refers to a given reality, be it abstract or concrete. Charles Peirce, the philosopher who has conducted the most elaborate study of signs, sees a symbol as a type of sign, the latter being his basic semantic category. Peirce (1932) believes that all modes of thinking depend on the use of signs. For him, every act of reasoning is a function of the interpretation of signs. Thus, signs mediate between the external world of objects and the internal realm of ideas. According to Peirce, a symbol is a sign which refers to the object it denotes by virtue of a law. For him, a symbol is technically a sign which refers to the object that it denotes by virtue of a law, usually an association of general ideas, which operates to cause the symbol to be interpreted as referring to that object. Symbols are, therefore, associative representations of objects or social realities. They are not mere representations of pictures or abstract ideas, as do normal signs, but are deemed to be symbolic signs because there is a “semiosis” or “cooperation” between the given objects and their symbols. A symbol is different from a mere sign in the sense that it reveals a reality that is beyond what a sign would normally indicate. Dukor (2006) explains: Symbols are cultural realities imbued with cultural meaning and any suggestive symbol…is epistemic and thematic. It is an overt expression of the reality behind any direct act of perception and apprehension, which really possesses scientific connotation outside its normal, obvious or conventional meaning. Above, Dukor refers to a symbol as “an overt expression of the reality behind any direct act of perception”. This is noteworthy because reality is not independent of human consciousness but consists of symbols or objects and events as perceived by the human mind. Symbols enable humans to understand and communicate their awareness and interpretation of their physical, social, spiritual, and cultural environment. A symbol makes sense within a given semiotic code. Explaining this post-Saussurean term, Chandler (2019) says that every symbol “as part of its social use within a code” makes sense within a historical and connotative context to “members of the sign-users’ culture”. This echoes Saussure’s position that “language is always an inheritance from the past” (Duan 2012) users are compelled to accept, a view Lévi-Strauss (Chandler 2007, 27) also expresses when he maintains that “the sign is arbitrary a priori but ceases to be arbitrary a posteriori – after the sign has come into historical existence it cannot be arbitrarily changed”. This historically fixed nature of the symbolic sign is one of the elements that imbues it with cultural relevance and stability and enables certain symbols to emerge as core symbols. 4. Core Symbols Core symbols offer the surest guide to the identification and understanding of a cultural group’s essence, defining values, and characteristic behaviour. According to Poon (2018), symbols, as cultural materials, in being used to “to signify ideas, beliefs, actions, events or physical entities” are “instrumental for human communication and commodification”. Paraphrasing Hall (1996), he stresses that: The study of symbols seeks to understand symbolic forms of mediation and the mediated, and aims to critically demonstrate symbolic construction in its cultural role as meaning-makers in postmodern era. One of the first major philosophers to appreciate the meaning-making role of symbols in terms of their power to organise both thought and action is Susanne Langer. In her indepth study, Philosophy in a New Key: A Study in the Philosophy of Reason, Rite and Art (1954), she says that “the human brain is constantly carrying on a process of symbolic transformation” of experience because “the main themes of our thought tend to be transposed” into symbols. Core symbols are those symbols which reflect and represent the main themes that energize the belief system and customary practices of a cultural group. Though this paper is not about “the logic of meaning” in a general sense, Langer’s thoughts and assumptions in this regard would illuminate our basic understanding of symbolic meaning, and it is necessary to let her explain this in her own words: Meaning has both a logical and a psychological aspect. Psychologically, any item that is to have meaning must be employed as a sign or a symbol; that is to say, it must be a sign or a symbol to someone. Logically, it must be capable of conveying a meaning, it must be the sort of item that can be thus employed… Both aspects, the logical and the psychological, are always present, and their interplay produces the great variety of meaning-relations over which philosophers have puzzled and fought…(Langer 1954, 42-43) Langer goes on to assert that there is no quality of meaning because meaning is logically derived and logic does not deal with quality but with relations. Even then, meaning may not be said to be a relation as a relation is mostly viewed as “a two-termed affair”. She prefers to see meaning as “a function of a term” because a function is “a pattern viewed with reference to one special term round which it centers”, stressing that “this pattern emerges when we look at the given term in its total relation to the other terms about it” (44). In functional terms, therefore, we can share this view by stating that a symbol is regarded as a core symbol in terms of its total relation to the other cultural elements that contextualize its symbolic pattern. This means that there can be a shift in the core essence of a core symbol if the semantic values of the cultural elements that circumscribe its meaning change over a given period of time. This is why a core symbol’s meaning is not instinctively or infinitely fixed. Its meaning can be modified, reviewed or even lost over time. Cowries, for instance, used to be the core symbols of wealth when they served monetary purposes across Africa. When they lost their value as means of exchange, with the emergence and dominance of bank notes and coins, they lost their long-term role as symbols of wealth. In spite of their symbolic decline, as noted above, cowries proved more resilient than some other discarded traditional symbols, such as red mud, that became mostly irrelevant after such demotion. Cowries continue to function today as cultural symbols because the user communities reverted to using them for decorative, theatrical, and medicinal purposes (Ngangah 2013). When cowries ceased to serve as means of exchange, they became easily available to the common folk who now use them to decorate clothings, household items, and masks. Their theatrical uses are seen in custumes won by cultural troupes, masquerades, and dancers. Their use in traditional medicine is chiefly in divination and fortune-telling, which are key pre-clinical tools used by traditional healers across Africa to identify the spiritual cause of a serious disease. The changing fortunes of cowrie, in terms of its symbolic roles, indicate that symbolic transformations are continual and epochal in nature and that major shifts in symbolic meaning are possible within someone’s life time. Symbols are not immutable. As people and societies that imbue them with meaning change in physical, spiritual and psychological terms, the symbols by which they define and explain their various shades of existence undergo alterations that moderate or alter the essence of their symbols. With the exception of few radical departures from the past, such changes are usually gradual and cut across generations, and this make them barely discernible to most observers. Thus, there would always be occasional, though infrequent, need to determine and re-determine what constitutes a given culture’s core cultural symbols. As earlier noted, this is a sine qua non for assessing a cultural group’s symbolic uniqueness, identity, and value. To avoid making the determination of the core cultural symbols of an ethic group an arbitrary, non-uniform, and unreliable exercise, a set of generally applicable parameters by which to gauge the cultural relevance of symbols needs to be put forward. This is what we would try to do and illustrate in the next section of this study. 5. Parameters for Identifying Core Symbols The word, “parameter” is loosely used here as an identifiable and measurable characteristic or distinguishing feature by which a symbol can be classified as “core” or “peripheral” within a given cultural belief system and practices. The usefulness of a parameter, in most ordinary contexts, lies in its universal or non-specific applicability. For example, if an examination board sets the pass mark at 50%, it should apply to all courses and all students for it to be a predictable and reliable determinant of whether a student has passed or failed a course. Just as in the above simple example, a parameter is usually derived from the elements or attributes of the system which it is meant to gauge or quantify. For instance, in our example, the number of marks (expressed as a percentage) earned by a student is used to determine whether he has passed or failed. If his personal relationship with the teacher, rather than his performance in an examination, is used in awarding marks to him, then that yardstick cannot be considered a parameter because it is extraneous to the usual system of testing and grading students. Before we go into the parameters we have identified for the purposes of determining core cultural symbols, let us briefly explain what we mean by “core” and “peripheral” symbols. Every society has its cultural pillars or those elements of cultural beliefs and practices that define and sustain its key beliefs, values, institutions and essential practices. Symbols which are used to represent these elements or their respective essence are core symbols while symbols which signify other cultural elements (such as a palm wine tapper, the death of the king) or cultural events (such as the pre-marital fattening of the bride among the Ibibio) are peripheral symbols because they have no direct relevance to the essential and central functions of the cultural group. Having said this, we can now turn to the parameters for evaluating core cultural symbols. Although what may qualify as core cultural symbols can differ from one culture to another, the under-listed set of parameters derived by this researcher in the course of his years of conducting research in the area of cultural philosophy constitutes a theoretical framework which can be applied to identify and set apart a cultural group’s core symbols from its peripheral ones. There are six parameters this researcher has used and found helpful in this regard. The parameters are used only in determining if a cultural artefact is a core symbol. By artefacts we simply mean those modes of transmitting cultural beliefs and practices that are found among all cultural groups. According to Bauman et al (1972), three forms of artefacts are universally acknowledged; they include:

An artefact would be regarded as a core symbol if at least 50% of the parameters mentioned below are applicable to it. So, it is possible that if three artefacts are tested using these parameters, one may be rated 50%, another 70%, and another 100%. Because they all measured at least 50%, all would be regarded as core symbols although it is clear that their degree of cultural weight, acceptance or popularity obviously differs. This difference can be critical, as we would see later in this study, when gauging which cultural artefact should be adopted to serve a specific cultural or research purpose. All artefacts that score less than 50% when measured for degree of cultural relevance, using these parameters, should be regarded as peripheral cultural symbols. Below, then, are the parameters for gauging the status of a cultural symbol, whether it is a core cultural symbol or a peripheral cultural symbol:

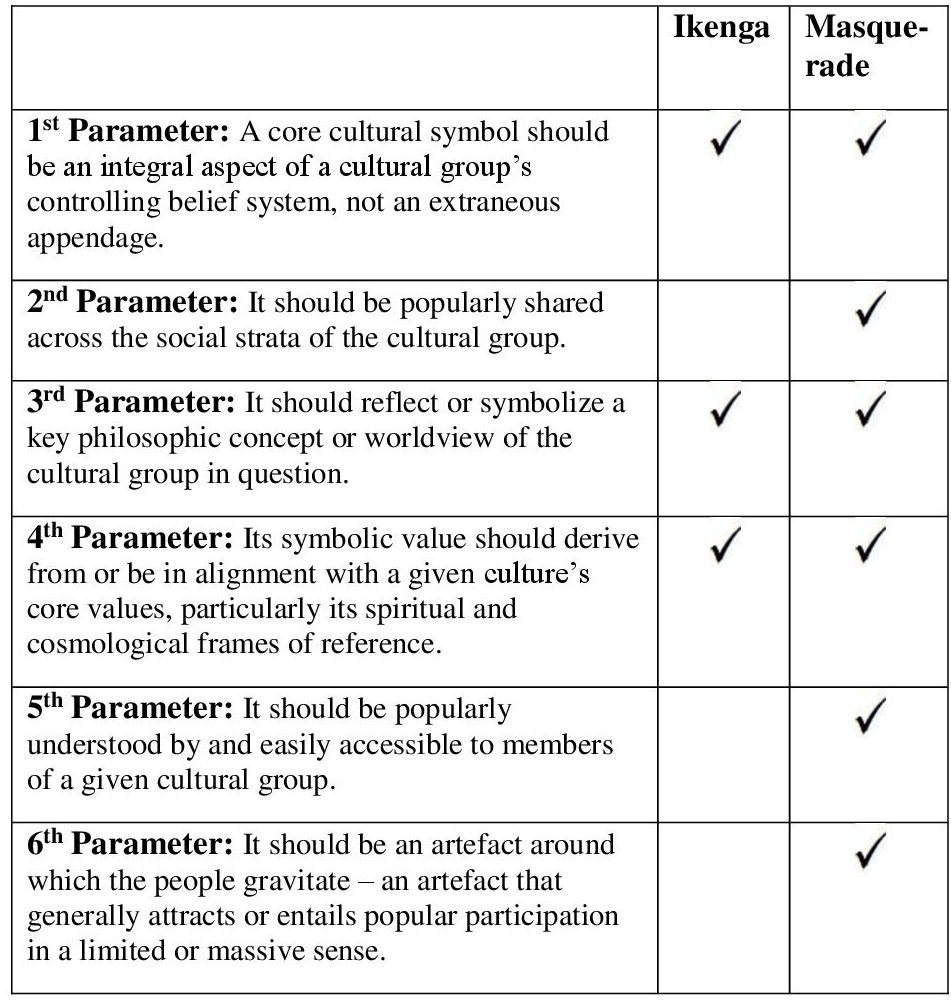

This researcher recently conducted a study among the Igbo of eastern Nigeria where he needed to determine which of the two key Igbo symbols, ikenga (a horned deity of the Igbo) and the Igbo masquerade, he should use as a core cultural symbol for the research. The fact that both were common core Igbo cultural symbols made it even more difficult to choose one over the other. For the purposes of the research, he needed to choose the most common core cultural symbol of the Igbo. Having narrowed his choice to these two Igbo cultural symbols, the question was: which of them, ikenga or the Igbo masquerade, is more of a core cultural symbol than the other? To answer this critical pre-research question, the six parameters were applied in comparing ikenga and the Igbo masquerade and below is the result:

As we can see, the Igbo masquerade doubly outscored Ikenga. The researcher, thus, adopted and regarded it as the most common core cultural symbol of the Igbo. Indeed, no largely non-verbal cultural expression in Igbo land is as popular and widespread as the Igbo masquerade act and certainly none offers as much drama, variety of music, colour, sport, and all-round fascination as much as the theatrical complements masquerades bring to enrich events and enhance audience participation. 6. Conclusion Let us note, as we conclude this study, that parameters mean different things to different people, depending on their area of discipline. What a parameter means in linguistics is different from what it means in engineering, mathematics or statistics. And no matter how it is expressed (as an equation, a function, or a simple set of rules, such as the above 6-point parameters), a parameter is not a variable value (Kilpatrick 1984). A parameter is a fixed value. It does not change with circumstances and is not arbitrarily altered. None of the six parameters we have identified should be altered to suit a particular cultural or research need. It is either a cultural artefact wholly satisfies the specific demand of each of these parameters or it does not. This is the spirit behind this set of rules which, it is hoped, may be of some benefit to a cultural philosopher or scholar conducting a research that necessitates the identification of a cultural group’s core cultural symbols. If this study has made some contribution towards the design and application of general parameters for determining not only the core symbols of cultural groups but those core symbols’ respective level of authenticity and relevance, then the main goal of this study would have been achieved. As Langer (43) has rightly noted, “the whole purpose of general concepts is to make the distinctions between special classes clear”. References Bauman, Richard; Paredes, Americo, eds. Toward New Perspectives in Folklore. Trickster Press, 1972 Chandler, Daniel. Semiotics: The Basics. Routledge, 2007 Duan, Manfu. “On the Arbitrary Nature of Linguistic Sign”. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, Vol. 2, No. 1, Academy Publisher, pp. 54-59, January 2012 doi:10.4304/tpls.2.1.54-59 Dukor, Maduabuchi, “Theistic, Panpsychic Animism of African Medicine”, Essence, Vol. 3, 2006, p.xvi https://www.amacad.org/humanities-indicators/higher-education/racialethnic-distribution-degrees-philosophyhttps://www.reference.com/culture Kilpatrick, James J. The Writer’s Art. Andrews McMeel Publishing, 1984. Langer, Suzanne K. Philosophy in a New Key: A Study in the Philosophy of Reason, Rite and Art. New American Library, 1954. Ngangah, Innocent. “The Epistemology of Symbols in African Medicine,” in Open Journal of Philosophy, Vol 03, Iss 01, 2013, pp 117-121. Poon, Stephen. Symbolic Perception Transformation and Interpretation: The Role and Its Impact on Social Narratives and Social Behaviours. IAFOR Journal of the Social Sciences, Vol. 3, March 8, 2018. Trimmer, John D. Response of Physical Systems. New York: Wiley, 1950. Urban, Wilbur M. “Symbolism in Science and Philosophy” Philosophy of Science, Vol. 5, No. 3 (Jul., 1938), pp. 276-299. https://www.jstor.org/stable/184835. Wagoner, Brady. Symbolic Transformation: the Mind in Movement through Culture and Society. Routledge, 2009. Weiss, Charles Hartshorne Paul (ed.). Collected Papers of Charles S. Peirce. Harvard University Press, 1932. |

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||