International Journal of General Studies (IJGS), Vol. 4, No. 1, March 2024 https://klamidas.com/ijgs-v4n1-2024-04/ |

|||||||||||

|

Themes and Settings in Nigeria’s Heritage of Folk Narrative By Bukar Usman

Abstract This paper, explores Nigeria’s heritage of folk narrative as elicited from the outcome of the pan-Nigerian folktale-collection research sponsored by the Dr Bukar Usman Foundation in 2013. The nation-wide research lasted for three years and its outcomes have been collated, edited and published in five voluminous books by the author of this paper. The paper, part of the author’s A Selection of Nigerian Folktales: Themes and Settings, is his introductory insight into the nature of themes and settings found in thousands of folktales collected from folktale traditions across Nigeria. The paper is in six parts. In part one, he provides a historical survey of folk literature in Nigeria. In part two, the author states and analyses the significance and defining traits of the folktale genre. The author’s motivations for embarking on the research as well as his research methodology are discussed in part three. The cultural and narrative similarities found in the about 4,000 tales collected from communities across Nigeria are highlighted in part four. Part five discusses issues connected with the classification of the collected tales; it throws light into the author’s decision to classify the 700 tales of his A Selection of Nigerian Folktales: Themes and Settings into 18 classes. The author’s concluding remarks constitute part six. It should be noted that all references to specific folktales, unless otherwise stated, are pointing to folktales published in A Selection of Nigerian Folktales: Themes and Settings, the first published book of the five books that emerged from the author’s momentous nationwide folktales research effort. Keywords: folk narratives, folktales, themes, settings, Nigeria, folktale classification

Almost every human society, from the most unsophisticated to the most urbane, has a heritage of folk narrative. It may be a living, dying or dead heritage but folk literature has always been a vital aspect of the oral tradition of most societies. Cultural expression among literate people is largely written or electronically transmitted whereas oral tradition is the most dominant form of cultural transmission among non-literate people. The Nigerian society is partly literate and partly non-literate, and this mixed reality is reflected in the quality, quantity and demographic spread of its folk narratives. To what extent these factors have affected the thematic concerns of the country’s oral narratives may not have been nationally surveyed, but various collections have shown that Nigeria has a vast and remarkably rich folk narrative tradition. Although moonlight tales, told mostly to the young by older family members, come to the mind of many when folk narratives are mentioned, folk literature covers a much-wider area of cultural expression. It includes tales of cosmic, historical, mythic and ritualistic value, and children are not the target audience of these types of tales. This category of tales belongs to adults and is the philosophical and religious foundation of the ethnic or sub-ethnic group. Elders, not children, are the traditional audience and guardians of these tales of primary social and customary importance. The values the moonlight tales espouse are rooted in the tenets enshrined in these elders’ tales which, unlike the common folk tales, are communally respected as non-fictional facts. These non-fictional tales are not included in this anthology. Being tales of “history,” they will be documented in Book 4 of this series (Treasury of Nigerian Tales). The tales in the present collection, representing the age-old narration of Nigeria’s common folks, constitute Book 2, which is devoted to the everyday tales of the people. Nigeria’s folklore (traditional knowledge, beliefs and practices) has largely survived by word-of-mouth transmission. But certain aspects of our lore have been documented by cultural anthropologists, missionaries, who pioneered Western education in the country, and other scholars and authors. The motivation, for the foreign enquirers, was their desire to access the core of our people’s values through a researched exploration of our folkloric expressions, particularly our rituals, mythologies and folktales. Accessing and understanding the latter, in particular, became the key to their understanding of the moral values of the people they had colonized. Bridging the cultural divide was a major challenge for the foreigners, who tackled the matter primarily by observing, learning (via interpretation), and documenting the local languages and some aspects of the people’s way of life.1 Those of them who could speak the local languages played pioneering roles in linguistic and other forms of cultural documentation. Available records show that the missionaries, who were more interested in the social circumstances of the people, paid more attention to folklore, education (including practical language studies), and health than colonial government anthropologists who emphasized issues of political institutions, geography, mineral resources, trade and linguistics. Because of the earlier-stated reason, their interest in the folktales of our local communities gained prominence over the attention, if any, given to other aspects of our folklore, such as traditional art, music, dance, rituals, architecture, and medicine. Folktales were so overtly emphasized by the colonial educationists that even the neglected aspects of our indigenous folklore were indirectly acknowledged through the tales they promoted. For instance, the core of the community programme drawn for schools ran by the missionaries in colonial north-eastern Nigeria included a folktale-based “curriculum with specific objectives.” In actualization of that novel educational approach, Babur-Bura folktales were collected and classified under sub-headings such as Health Folklore, Agriculture and Livestock Folklore, Crafts Folklore, and Home and Social Life Folklore.2 Among many Nigerian groups, there were similar research interests in related aspects of our folklore, one of the most notable being Kay Williamson’s studies in the language and proverbs of Ijaw people of south-southern Nigeria3 and Susan Wenger’s participant-observer lifelong promotion of south-western Nigeria’s Yoruba groves and divination practices.4 Divination tales, which shall be collected in Book 4 of the Treasury of Nigerian Tales series, usually come out of such practices.5 Fortunately, these foreign researchers left written records of their findings. Hence, the first exercise in researching and publishing aspects of Nigerian folklore were undertaken by foreigners, although few of these foreigners, markedly Wenger and Williamson, ended up, by their passionate involvement, being deemed authentic indigenes. Some notable publications by these European authors wholly or partly devoted to folktales include African Stories6, In Sunny Nigeria7, Hausa Tales and Traditions8, and Education of Primitive People9 There was hardly any missionary group that did not publish some folktales in their magazines and special publications. Before and after Nigeria’s independence in 1960, a number of Nigerians who had acquired Western or Arabic education took ownership of this cultural documentation and gave it indigenous flavour in their fictional works. These works were published in English and in the indigenous languages. Such indigenous works from the northern part of the country would include Abubakar Imam’s books, the most notable of which was Magana Jari Ce. In southern Nigeria, Pita Nwana’s 1935 fantasy novel, Omenuko, made enduring impact in the Igbo-speaking parts of the country. These publications drew significant inspiration from motifs closely associated with folk narratives. In pre-independent South Western Nigeria, the effective writer, D.O Fagunwa, showed “an extensive use of proverbs, riddles, traditional jokes and other lore central to Yoruba belief.”10 That writers from Northern Nigeria made an early but modest mark in novel-writing in an indigenous language is attested to by the following: In various parts of the country, novels developed around 1930. Centered upon fantastic, magical characters of humans and fairies, Hausa novels, called “non-realistic novels,” were based on folktales. The “mysterious” characters transmuted into other beings; fairies, animals, and humans all conversed among one another.11 On Muhammadu Bello’s fantasy novel Gandoki, Bade Ajuwon comments, “One is led to say that the book is a reduction of Hausa oral tradition to written literature.”12 Amos Tutuola was a notable Nigerian writer who drew fundamental inspiration from the folktale genre but communicated his tale in a unique brand of the English language. His The Palm Wine Drinkard was among the first books that introduced Nigeria’s folk narratives to English readers. In structure and motif, Tutuola’s stories were inspirationally pulled from the traditional repertory of Yoruba folk narratives. Tutuola’s English-language style did not attract followership but his bold recreation of indigenous oral narratives inspired writers from other parts of Nigeria. An example of a similar narrative from south-eastern Nigeria was Uche Okeke’s Tales of Land of Death. Because the folktale in its more complex form shares striking resemblance with the short story, a number of Nigerian writers easily turned to the modern short story as a narrative option in the 1960s and 1970s. Their stories were published in Okike, Black Orpheus, West Africa, The Nigeria Magazine, and a few other magazines. Some of those whose short stories were featured in those periodicals later published individual books of short stories. One of such short story writers was Cyprian Ekwensi whose Lokotown and Other Stories was published in 1966, four years after the publication of Chinua Achebe’s Sacrificial Egg and Other Stories. All of these and subsequent literary developments in Nigeria were preceded by, and indeed had their roots in, the oral tale. The oral tale is the precursor of the modern short story and, indeed, of the novel. For many people around the world, their first understanding of what life is all about began with their introduction to the morals of the oral tale. For many generations of Nigerians, the moonlight folktales they had relished as children became the bedrock of their social, psychological and ethical development. Across Nigeria, in different families, folktale narration was a regular nightly experience. Unfortunately, the practice is dying out in the villages and is almost non-existent in the cities. Even if we must lose the tale-telling sessions to the exigencies of urbane life, it is the overall goal of this anthology to capture in print, for the present and future generations, a translation of various folktales collected from different parts of Nigeria. This editor and his team of resource persons embarked upon the project because of their passionate awareness of the importance of folk narratives in personal and societal development.

It is difficult to value something without first understanding its defining traits and significance. The oral nature of the folktale and the anonymity of its author or authors are its most basic defining traits. All the tales of this anthology were orally transmitted from generation to generation. Following the invention of printing, folktales have been collected and published in different countries. Even in print, the authors of those generational folktales remain anonymous. A folktale belongs to its communal origin even where its elements have been changed by different narrators who introduced one form of embellishment or the other as the story is retold from generation to generation. This is why it is difficult to ascribe the authorship of a folktale to one individual. An individual, however, may write a tale, as Aesop did, but that would be a literary tale, not a folktale. A folktale, strictly speaking, belongs to the community. This brings us to the question: why folktales? What is the significance of the folktale? In the past, it would have been unnecessary to ask this question. From their early childhood to their teenage years, children in Nigeria were accustomed to listening to folktales every night and just grew up knowing that folktales were important building blocks in their lives. Things have now changed. Television, the internet (especially Facebook and YouTube), mobile phones, and computer games are now alternative and easier-to-access forms of entertainment. In those days, one would need to have members of a story-telling audience gather in one place and a willing story-teller to hear and enjoy a story. In these days of electronic gadgets and the web, today’s teenager, for instance, can with the tip of the finger personally access various forms of entertainment and miscellaneous data, including indecent and unhealthy information and images. And this typical teenager’s younger siblings, who are not yet above ten years, also exercise their own reckless independence. With the remote control, they can easily comb through their family’s satellite television, watching immoral or violent programmes from channel to channel. They know little or nothing about the symbolic heroes of their indigenous folktales but are very familiar with electronic characters like Tom and Jerry, Ben 10, and Spider Man. Unless parents and guardians have a way of administering parental control and also ensuring that sound moral training accompanies their children’s electronic attractions, their children are likely to grow up morally and culturally imbalanced. Folktales play a fundamental part in this moral and cultural balancing exercise. Below, we will look at four basic functions of the folktale in terms of the benefits an audience could derive from listening to an oral tale or reading/listening to a documented one. These benefits are applicable in developing societies, such as ours, as well as in highly industrialized ones. There are many benefits of the folktale but we will look at four key advantages below. a. Promotes a Sense of Community: Traditionally, folk stories are orally transmitted from generation to generation within a group or groups of people. This could be people within a clan, tribe, nation or people of a common background within a plural urban setting. It is within such groups that folktales are orally narrated or read out from a printed text for the common enjoyment of the audience. Apart from the stories, other group activities, such as exchange of riddles and jokes, quizzes, and pleasantries, take place. A lot of laughter accompanies story-telling sessions and the cordial environment, sometimes, is made more exciting by the provision and sharing of light refreshment. All of these generate a feeling of camaraderie, oneness, unity, love, and group loyalty and dedication. This story-hearing engagement within a mass of people of shared cultural interest gives every involved individual a sense of togetherness and social relevance. Such a story-telling engagement fosters a sense of community in children and lays a sound moral foundation on which they could grow to become responsible citizens. This benefit conforms with the integrative role of this mass but oral media, according to the individual differences theory which proposes that individuals respond differently to the mass media according to their psychological needs, and that individuals consume the mass media to satisfy those needs. The need may be for information (e.g. providing statistics about players and teams), integrative (offering a sense of belonging to a group of similarly interested people), affective (e.g. by providing excitement), or escapist (helping to release pent-up emotions).13 There is need to revive in our homes the traditional story-telling sessions as a basic way of countering two of the most negative disadvantages of our so-called globalized but highly individualistic society, namely, acute selfishness and inequality. Excessive individualism, with the selfishness, greed and other social vices it breeds, is ruining societies today. Collective story-telling sessions engender rapport among members of the audience and other social groups with whom transmitted folktales are later shared. Furthermore, sharing folktales, and the cultural education conveyed thereby, reinforces the precept that every member of the community is connected and bonded to another. Such sense of identification with a communal group is naturally extended beyond the scope of the story-session group to the wider society. b. Imparts Positive Common Values: Folktales, whether orally delivered to a group audience by a story-teller or individually accessed through printed or audio/visual means, impart positive social values as well as the particular beliefs of a given ethnic group, nationality or culture. The values being referred to here go beyond the morals sometimes drawn at the end of a folktale. What we have in mind here are the recognizable values and beliefs built into the fabric of the tale. These values are embedded in the tale through its various elements and a single tale might contain more than one of such values or customary beliefs. For instance, universal values such as respect for elders as well as culturally-oriented beliefs, such as the belief in many communities that the youngest sibling is usually the smartest, can be re-echoed in the same folktale. Positive values clearly identifiable from the theme, plot, characterization and cultural components of folktales can be broadly grouped into family values, social values, religious values, economic values, educational values and aesthetic values. The specific traits emphasized would depend on the cultural preferences of the story-teller and those of his listeners. The above reference to “religious values” does not necessarily point to the major world religions but rather refers to the indigenous gods, myths and rituals of a given group or story-listening audience. Understanding these cultural aspects and their symbolic significance is necessary for a culturally-relevant appreciation or interpretation of a folktale. For instance, a non-Babur/Bura listener may fail to interprete an appropriate crocodile character in a given tale as being the spiritual or symbolic double of the Biu Chief just as an uninformed non-Yoruba listener may miss the symbolic representation of Ogun as the Yoruba god of iron. So, there are more to folktales than the fairies, animals, and strange creatures that characterize them. Tales contain societal values and cultural beliefs, and it is important to underscore this by citing verifiable examples from the stories published here. In “The Goat with Three Tails” (Story No. 32), we see the interesting scenario where the killing of a goat by the chief priest of a shrine attracted the death penalty and led to his instant execution. The story highlights the cultural as well as the universal value of fair trial. Most readers would recognize the universal dimension but may miss the cultural. Let us distinguish the cultural value from the universal. An abnormally-born wild goat (“the goat with three tails”) was brought by hunters in critical fulfillment of the chief priest’s sacrificial requirement for the healing of the community’s terminally-afflicted king. But the goat, speaking for itself, had requested that it should be spared and offered its captors a forest herb which it swore would heal the king. At the shrine where the goat was to be sacrificed, the goat’s captors pleaded with the chief priest to administer first the recommended herb: if the herb revived the king, the goat would be freed; if not, it would be sacrificed. That was the agreement the captors, acting on behalf of the community, had reached with the goat. But the chief priest refused to give the captured animal the benefit of doubt and, against all entreaties by its captors, killed and sacrificed the goat with three tails. And immediately the king’s health became worse. Pressurized by the goat’s captors and the elders of the community, the chief priest reluctantly administered the goat’s recommended herb on the king. He instantly became well. Infuriated by the avoidable slaughter of the benevolent goat, the villagers killed the chief priest. The cultural precept executed here is what might be called the life-for-life, death-for-death principle. At the back of the story-teller’s mind is the traditional understanding of the nature and power of spiritual covenants. The captors had covenanted with the goat that administering the magic drug while sparing the goat’s life would revive the king’s own life. The chief priest invited criticism upon himself when he refused to respect this covenant. But the more covenant-minded villagers knew that slaughtering that goat was ominous. Had the obstinate chief priest been kept alive, the stability of the king’s health might not have been guaranteed since a vital aspect of the covenant (sparing the goat’s life) had been violated. The chief priest’s head had to roll after the head of the mysterious goat. This is a crucial cultural dimension of the value imparted by this story, and it is different from the universal fair-trial precept which this story also communicates. “Lala and Lele” (No. 38), “The Ikuoku Leaf” (No. 85), “The Man who Became a Chimpanzee” (No. 146), and “The Fat-Lips Woman” (No. 688) are some of the stories of this collection that illustrate both universal and unique cultural values. Whether universal or culturally localized, the values the listener or reader of a folktale, such as “The Goat with Three Tails,” derives are often common, communal, and socially stabilizing. But there are also uncommon individual virtues which can be drawn from folktales. While collectivism is emphasized, personal traits of courage, creativity, and compassion, among others, are also portrayed and encouraged. Similarly, dimensions of wickedness hatched in the hidden heart of the individual are flatly condemned by the manner story resolutions are appropriately plotted to disfavour the unjust. In tale nos. 106, 110, and 213, among several others, evil is punished. Tale no. 213 fittingly ends with the Babur/Bura proverb: “Let a man dig the hole of wickedness shallow because he may fall into it himself.” c. Teaches Ethical and Practical Lessons: It is a universally-assumed fact that folktales teach ethical lessons, but not all tales are narrated for the primary purpose of communicating a moral. Although life’s lessons can be gleaned from many tales, only the fable (tales that feature mostly animals and illustrate a moral, such as “The Lion and the Playful Mouse” [No. 381] and “The Hyena and the Monkey” [No. 402]) is essentially crafted to communicate morals. Others may simply aim to entertain or amaze the listener or reader; but even here, a meditative audience can draw practical lessons which may illustrate some realities of life. In many fables and other moralizing tales, the morals are stated at the end of the story and cannot be divorced from the story. Nowadays, story-tellers would simply tell their tale and expect the listeners or readers to draw the morals. In such cases, different morals can be drawn by different audiences. Indeed, there are stories that are told with the objective of posing a moral question at the end of the tale. A good example is “The Three Slaves” (tale no. 610) where a complex web of relationships between Gumsa, the central character, and four women dictated the really hard-to-answer question: “Among the four wives, who will be the wife after Dala’s heart? You think that you are clever, then who of the four shall be first of all?” We implore you to read this story and you will be amazed by how difficult answering this question, arising from a folk narrative, can be. The artistic complexity of the story itself indicates that not all folktales are simple straightforward narrations aimed at children. There are folktales for adults, and “The Three Slaves” is a good example of such tales. d. Entertains the Audience: Both the audience listening to the oral narration and the private reader of a folktale derive immense pleasure from the story. Although stock characters often feature in folktales, this does not detract from their entertainment value. What a character symbolises is already known to the audience familiar with the cultural interpretation attached to that character. Because of this cultural meaning imposed on it, a mere mention of a popular character, especially animal character, at the beginning of a story creates some excitement and suspense among the audience. Characters may mean different things in different cultural backgrounds. Every animal featured in a folktale has certain characteristics attributed to it by the local environment. For instance, in north-eastern Nigeria, the hyena is a symbol of greed, meanness and clumsiness. Among the Fulani, the rabbit is a symbol of cleverness, selfishness, and depravity. The tortoise, among all Nigerian groups, is a popular trickster and is noted for its cunnying, dubiousness, creativity, and breach of mutual agreements. Since the behaviour of such characters are fixed, the story-teller would usually rely on plot and surprise resolutions, among other devices, to enhance the effect of his tale. The story-tellers or oral narrators were usually older members of the family or the extended family: grandparents, parents, older siblings, uncles, aunties or any other person competent enough to narrate to the younger generation the imagination and wisdom of the ethnic group as embedded in the folktales. The story-telling sessions took place at night and the setting could be indoor or outdoor, the latter being the obvious choice in the dry season. In traditional environments, the indoor setting was usually inside a hut big enough to accommodate the group of young listeners from different families. The outdoor setting could be in the open in front of one of the closely-spaced huts within a fenced or an unfenced compound. In those days, right from the start of the tale, every narrator tried his or her best to carry the audience along. There were no dull moments. The children expected fresh entertainment and were hardly disappointed as they were fed with different kinds of stories each night. Even where the story had earlier been narrated, there was no loss of excitement, particularly where the current narrator was some one adept at refreshing a well-worn story by creatively stretching its plot to accommodate new characters, new conflicts, fresh suspense and surprising resolution. Every new narrator, by his or her own method of oral delivery as well as gesticulations, usually told the same story differently. There were narrators who occasionally engaged some members of the audience by asking them to guess a character’s next move out of a tight situation, and there were those who incorporated new choruses to cheer up their audience and enliven their tale. These were some of the reasons oral performances were so wonderful in those days when folktale narration was a regular nightly programme of families in many communities across Nigeria. Uche Ogbalu captures a typical experience among the Igbo, but this is also true of folktale story-telling sessions among other Nigerian ethnic groups: a careful observation of the folktale performing sessions show that neither the performer nor his audience is ready to move out of the scene. None shows sign of getting tired of either telling the story or listening to the story. The folktale narrator is able to hold his audience for hours…without the audience getting tired. Folktales are introduced to a traditional Igbo child from infancy. This means that the traditional Igbo child starts appreciating folktales from infancy to adulthood… In performance, the audience participation is assured. The audience sings the chorus, claps hands and even corrects the performer whenever he deviates from the normal routine of the story. That is why one can rightly assert that folktales are communally owned.14 One of the reasons the audience’s attention was retained over a long time during an oral performance was the fact that the same story was hardly re-told to the same audience. Each narrator often tried to tell a story he believed an earlier narrator might not have relayed to the given audience. This writer, as a child growing up in Biu, in north-eastern Nigeria, was a regular member of a folktale audience, and had some times wondered how the narrators’ resource of folktales seemed so inexhaustible. There were not just many stories but an interesting diversity of them. The makumtha, as the folktale is called in Babur/Bura, remains an educational and entertaining evening programme, although story-telling sessions are no longer regular events in most families. During group story-telling sessions, which are still held in some communities, much of the entertainment value comes from the dramatic aspects of the session. One is referring to the narrator’s vocal and body orchestrations, to those junctures in the story when the narrator and the audience jointly sing choral songs, and to the segments of riddles, quizzes and jokes that usually accompany such oral performances. In some communities, the folktale is further advanced into outright drama, especially in a situation where a standing performing troupe is in existence. Themes covered by such dramatic performances may be stretched to include some current realities, thereby making the show satiric and more entertaining. As Peek and Yankah have observed, folktales, in traditional communities, are inseparably linked to other forms of folk performances: The sheer diversity of folklore forms is striking. Puppet theatres still perform among the Tiv and Ogoni of Nigeria and in Mali. Masquerades continue to develop and adapt new characters in the rural areas and to find revitalized expressions among urban populations. Synthetic raffia, enamel paints, plastic parts, whatever: all can be used. The increasing use of Theatre for Development has revitalized traditional drama forms, from masquerades to folktalke sessions…Narratives filled with the exploits of tricksters and heroes entertain and advise their audiences.15 Outside the traditional environment of a given folktale, school or youth groups can still take the printed folktale and bring it to life through exciting oral narration or guided dramatization. But most readers of a good folktale will find that merely reading the folktale is itself entertaining.

The folktale, though a useful tool of character formation, moral transformation, cultural authenticity, communal harmony, and educational entertainment, is endangered today. In spite of the beneficial nature of Nigeria’s oral narratives and the creative spin-offs noted above, little is being done by governments, communities, schools and parents to preserve and promote our rich heritage of folk narratives. Inter-generational transmission of these tales via nightly story-telling sessions is a rarity these days. Very few children are today regaled with tales by moonlight, and this is the traditional mode of the folktale’s intergenerational transmission! A lot of parents and guardians, overwhelmed by the challenges and pressures of today’s urbanized world, have little or no time to be with their children, let alone tell them stories. Young people, too, have their own distractions and alternative forms of entertainment. This situation is worsened by the fact that many of the original languages of these tales, the indigenous languages, are either endangered or disappearing. Many youths no longer speak their mother tongue. In many homes in Nigeria, English or pidgin English is the language of communication because of the failure of parents to teach their children their mother tongue. And since, among Nigerian groups, folktales are rendered in the mother tongue, it follows that language endangerment or disappearance corresponds to the endangerment or disappearance of an ethnic group’s folktales and other aspects of its folklore. This writer has examined this matter in greater detail elsewhere.16 It should be enough to observe here that these issues of urbanization, nationwide failure in the intergenerational transmission of folktales, and the reduction in the use of the indigenous languages (the original and generational narrative vehicle of the tales) have made it necessary to collect and preserve Nigerian folktales for the present and future generations. To do this would entail extensive nationwide research in the collection and documentation of Nigerian folk narratives. This was the task the Dr Bukar Usman Foundation (DBUF),17 presided over by this editor, chose to undertake in 2013. For the original inspiration for this and related compilations, we need to go back to 2005, the year The Bride without Scars and Other Stories, this editor’s first book of modified folk stories, was published in English. Two English-language story books and 14 Hausa-language story books (now collected under the title, Taskar Tatsuniyoyi) were later published. It was while working on these books that one became fully aware of the nation’s enormous folklore resources and decided to begin the exploration by unearthing our rich but neglected folktales. The folktales field is a very wide one and the deeper one went the more one realized that the tradition has extensive dimensions. This editor began his exploration in Biu in 2004/2005 and was hoping to collect only a few tales for his first short-story books. The field proved richer than he had imagined. He collected over 1,000 stories within two years from Biu alone! Over 800 of such Biu stories were collected in the 1920s by the pioneer missionary, Dr. Albert Helser. Amazingly, as further investigations reveal, the Biu findings exemplify the abundance of folktales in many communities across Nigeria. This editor was further stimulated by his close association with the Nigerian Folklore Society and the Linguistic Association of Nigeria. The need for a nationwide exploration beckoned, and the Dr Bukar Usman Foundation considered it worthwhile to sponsor the project. This led to the inauguration, in early 2013, of the Nigerian Narrative Project (NNP or simply the Project in this report). The Foundation spelt out the following as its objectives for inaugurating the Project:

To carry out the tale-collection exercise in different parts of the country, the Foundation commissioned field teams led by informed co-ordinators who reported directly to Dr Bukar Usman, the Editor and President of the Dr Bukar Usman Foundation. Each team was asked to gather authentic folktales directly from the local folks. According to the guidelines, the tales should preferably be captured in the indigenous language of the narrator before being transcribed into English. Where practicable, every tale was expected to be captured during story-telling sessions, and such sessions were to be audio-recorded or videoed. In translating a story in an indigenous language into English, the translator was expected to reflect as much as possible the spirit and letter of the tale, its original idiom of expression, structure, and theme, and resist the temptation to over-summarize the story. Ten teams of researchers led by academic and cultural experts conducted tale-capture, tale-collection, and tale-translation exercises in various parts of Nigeria. Many tales were orally recorded. The field officers who worked under the coordinators utilized knowledgeable resource persons who were culturally conversant with the local communities. These local resource persons were responsible for organizing story-telling sessions which the field officers electronically captured. These local facilitators were also helpful in transcribing and translating the stories from the indigenous language into English. The outcomes of the field research were sent to the coordinator who compiled and sent them to the President of the Dr Bukar Usman Foundation, the Project’s initiator and Editor. This was the recommended procedure. Compliance in this regard varied from team to team. Some teams found it quite easy to adhere to the guidelines while others met on-the-field realities which made strict adherence to this methodology very challenging. Recording and collecting tales from the North-East was particularly difficult because of the activities of insurgents in the area. However, through informal means, and utilizing some documented sources as well, we were able to collect tales from some communities, and a number of tales from the troubled North-East are included in this anthology. Nigeria is a very vast country and while each team was encouraged to spread their tale-collection exercise to as many diverse communities as possible, logistic and other handicaps made it practically impossible for the Project to cover every ethnic or linguistic group. With over 350 ethnic groups and about 500 languages,16 Nigeria is remarkably ethnically and linguistically diverse. Suffice it to say that tales were collected from all states of the federation and the federal capital territory, Abuja. All in all, the Project’s dedicated teams operated creditably thereby fulfilling the Foundation’s dream of organizing an open, purely culture-driven, nationwide exercise that gave as many ethnic/linguistic groups as possible the opportunity of contributing their oral narratives. Some of the teams listed above went beyond their assigned areas to ensure that the oral narratives of many minority groups were captured. None of the teams concentrated their effort in the urban areas; all dutifully conducted research also in the rural or semi-urban areas. The researchers were required to spread the tale-collecting exercise into the communities in the remote areas because it would enhance their understanding of the cultural and traditional context of the tales. Some teams incorporated such cultural backgrounds in their report. It has been acknowledged that such cultural knowledge deepens the interpretation of a folk narrative and makes it meaningful to everyone, especially those who may not have been acquainted with the traditional values of the tale’s anonymous authors.

After months of field work in their designated areas, the research teams altogether turned in about 4,000 tales collected from communities across Nigeria and translated into English. Going through these stories was a wonderful experience. One could not but wonder why such cultural wealth was allowed to lie dormant for so long. While it must be acknowledged that some individuals and groups have collected and published Nigerian folk narratives in the past, most of the collections were based on the folktales of a particular group. The few volumes that included tales from different groups in the country were too slim to accommodate tales from most areas of the nation. Yet, judging from the outcome of this exercise, a sufficiently large pan-Nigerian collection is an educational, cultural, and social necessity. a. Common Narrative Attributes: One of the most unmistakable observations on reading these stories is the similarity of some of the tales across the ethnic groups. Linguistic differences, apart from their reflection in the naming of the characters and the wording of the songs, do not appear to be significant in terms of the nature and structure of the tales. Although this may sound surprising, especially in our ethnically diverse environment, many tales and episodes are common to many ethnic and linguistic groups. This and other common narrative attributes indicate that Nigeria has a unifying force in its folk narratives, a positive cultural bond Nigerians have failed to adequately acknowledge or celebrate. Many tales, as the reader himself would discover, can be cited to prove that certain episodes are common to more than one cultural group. An exciting example is “Why the Pig is always Digging” (tale no. 115), a tale collected from north-central Nigeria but is very similar to “Tortoise and Pig” (tale no. 130) from the south-eastern area. There are many tales that share such similarities across geographical and cultural boundaries. As to why such tales from different social contexts share similar episodes, two American anthropologists who had conducted research in West Africa offered this illuminating explanation: Our hypothesis is that this is to be explained by several factors: a relatively common historical experience, association with other clans (ethnic groups) through marriage, the incorporation of ingenious and appealing exploits attributed to another clan (ethnic group) into a new mythological system, and above all the play of the imagination on the traditional thematic resources…18 (Brackets mine) Common motifs are also noticeable across the collection. Some of the prominent ones include the cruel stepmother, the clever younger brother, the helpful ancestor, mermaid spirit, among others which will be listed, with examples, later in this write-up. These are motifs that spring from the cultural beliefs of the people or motifs adapted to suit such beliefs. Apart from common episodes and motifs, there is also similarity of character symbols. In most places in Nigeria, the main character of a typical folktale is the tortoise, and almost all the time the tortoise plays the role of a trickster. This is why the section on trickster tales is one of the longest in this collection; every segment of the country is represented here. Another common character found everywhere folk tales are narrated in Nigeria is the old woman, a symbol of benevolence who usually steps in to save embattled underdogs just when they are about to be drowned by the waters of antagonism or cruelty. There are some cultural and geographic variations, though. Among the Fulani, the tortoise is displaced by other animal characters such as rabbit and squirrel. And the section of this collection devoted to fisherman tales is dominated by stories from the south-southern part of Nigeria because of the preponderance of creeks and rivers in the area. In noting the above common features, warns the seasoned dramatist and literary critic, Ben Tomoloju, one should not deny the various cultural groups their own native creativity: a note of caution has to be sounded against comparative imputations that undermine the distinction of cultural expression. Even as migrations, borrowings and cross-cultural influences are major factors in cultural mobility, there are arguments for the distinction in the creativity of autocthonous communities. For instance, Ulli Beier notes that ‘similar ideas will occur to human beings in different places and at different times independent of each other.’ He illustrates this with the building of pyramids by the Azteks of Mexico who could not have had any contact with Ancient Egypt. As such, comparatism should not be so free-wheeling as to obliterate authenticity and originality…19 b. Common Cultural Attributes: Cultural diversity is a well-celebrated feature of the Nigerian society. Cultural similarities, while acknowledged, are not given the prominence they deserve. Some of the outcomes of the folk narratives project are close relationships in communal behavior noted by the researchers. Some of the observed common or similar cultural features noticed in these areas are: nature and style of traditional religious beliefs, family structure, social organization in rural communities, ritualistic practices, patterns of wealth acquisition and distribution, hero worship, and herbal medicine. We need not discuss all of these in this brief narration but we would further examine the issue of nature and style of traditional religious beliefs because of its broad narrative implications, as could be elicited from many tales. We would restrict our discussion to the relationship between the dead and the living, for this is our area of immediate concern as it will enhance the reader’s understanding of many of the tales published here. This is a concept of fundamental cultural and artistic importance the non-Nigerian or non-African reader of this collection will find helpful as background information. Among devotees of traditional religion in different parts of Nigeria, the living members of the community are not isolated human beings. In spiritual terms, they are believed to be linked to past and future members of their families, clans and the community in general. In other words, the dead, the living, and the unborn are believed to be in spiritual communion. The dead dwell in the world of the clan’s earlier dead and this world is ruled by ancestors. From this spirit world, the ancestors oversee the activities of the living, intervening now and then, mostly for good, in their lives. Within the context of African traditional religious worship, who are ancestors and what benefits do they serve? Ancestors…serve as mediators by providing access to spiritual guidance and power. Death is not a sufficient condition for becoming an ancestor. Only those who lived a full measure of life, cultivated moral values, and achieved social distinction attain this status. Ancestors are thought to reprimand those who neglect or breach the moral order by troubling the errant descendants with sickness or misfortune until restitution is made. When serious illness strikes, therefore, it is assumed that the ultimate cause is interpersonal and social conflict; serious illness is thus a moral dilemma as much as a biological crisis.20 From the devotee’s viewpoint, ancestral worship is the way the living acknowledges this special relationship. There is an aspect of this relationship which is not mentioned in the above quotation: some ancestors or some other dead member of a given clan may re-emerge in the world of the living through reincarnation. This is the traditional belief of some ethnic groups in Nigeria. Reincarnation is not essentially punitive and children believed to be “re-born” souls of ancestors are accorded special respect in many traditional settings. However, some of these children present special difficulties by the manner in which they die young and re-enter into their mother’s womb repeatedly. The Igbo call such a spirit-child ogbanje while the Yoruba call the spirit-child abiku, but belief in this phenomenon is not restricted to these two ethnic groups. Why does the abiku come and go? Traditional religious priests have many explanations but all are shrouded in mystery. One of the proffered reasons is that the ogbanje is visited upon a family when the ancestors want to punish the parents of this spirit-child for some moral foul they have committed or for habitually failing to appease the ancestors. Another set of heart-breaking children are the abnormally-born ones. They are believed to be a clear warning from the gods, particularly when they are born very deformed. These ones do not die young but grow up to become assertive individuals in spite of their handicap. In some parts of Nigeria, particularly among some communities in the South South, twins were once considered abnormally born children and their birth was seen as an evil omen. Attitudes towards twins have since changed and many families today cherish them as special blessings. Unlike twins, deformed or abnormally-born children are believed to possess supernatural powers which they can use against their enemies. They are typically seen as enfants terribles, and conflicts involving this group of characters are spread across many sections of this collection, especially the Enfant-Terrible subdivision. Tale nos. 87 and 104 are examples of stories featuring abnormally-born characters.

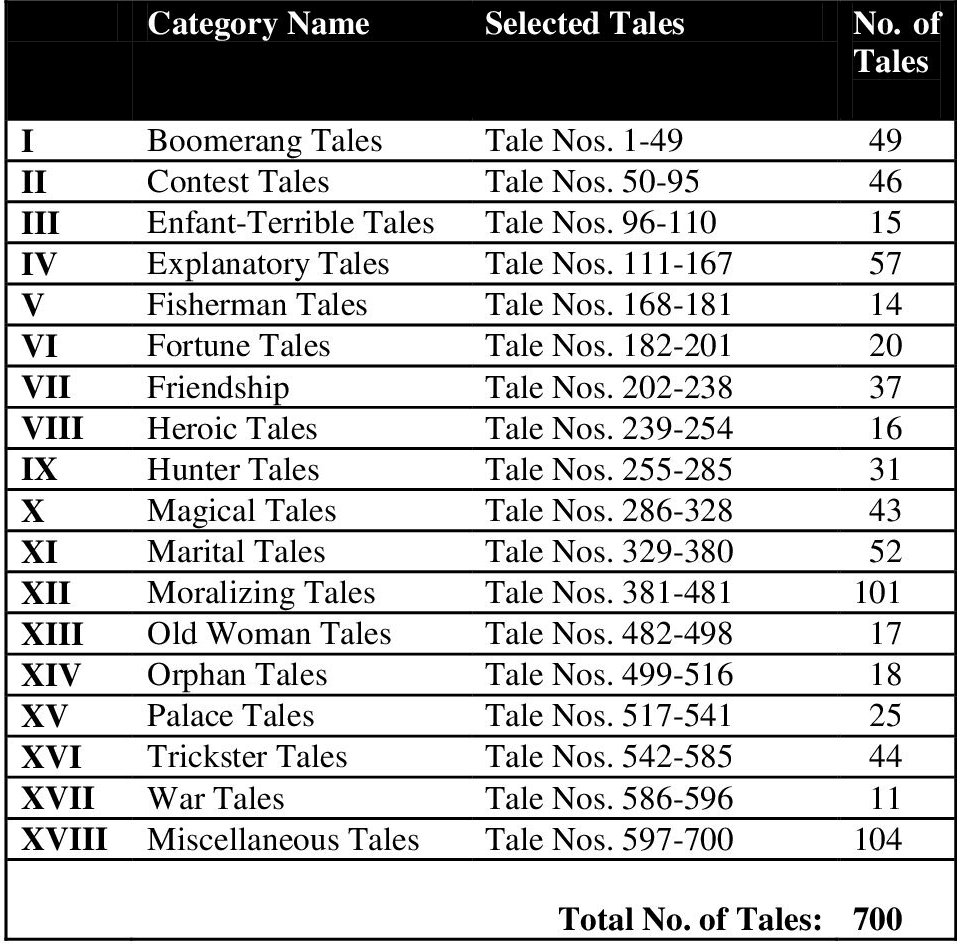

As earlier noted, about 4000 tales were collected across Nigeria. Most of the tales were narrated in the languages of their communal origin before being translated into English to make them accessible to all Nigerians and to the larger worldwide audience. The collected tales are not only many but diverse. To document them along the line of their cultural orientation as well as enhance the reader’s appreciation of their narrative import, we opted for a broad-based method of categorizing the tales. First, the collected tales (to be documented for record purposes) were sorted into two genres: Fictional Tales and Historical Tales. Historical tales, as their communal owners believe, consist of myths, clan or settlement chronicles, tales related to rituals and traditional religious practices, narrations about epochal historical events, origin and cosmic tales, creation tales, tales about legendary heroes and heroines, tales that explain the origin and nature of the world, tales about the exploits of the gods and about the Creator Himself. This category of tales is deemed to be factual even when the presumed facts seem too unfounded or too exaggerated to be considered true outside the cultural context of the tales. The other wide-ranging genre is the Fictional Tales class. This broad group refers to the common tales narrated by the common folks about the ordinary everyday experiences of the people. The range of themes or motifs covered by these tales include moral questions, human foibles, inter-personal relationships, kings and subjects, encounters with spirit beings, and journeys to the land of the dead, among many others. This category makes up the bulk of the tales gathered during the tale-collection exercise. The non-factual stories of this genre feature a variety of characters – human beings, animals, spirits, objects or a combination of one or more of these character types. These tales of anonymous authorship are, in terms of narrative form, mostly fairy tales, fables, ghost and mystery tales, and other story types. It is from the fictional tales class that the 700 tales of the anthology, A Selection of Nigerian Folktales: Themes and Settings were taken. A Selection of Nigerian Folktales: Themes and Settings, being Book 2, contains 700 tales which are grouped using parameters different from those used in classifying the tales slated for Book 3. The emphasis here is primarily themes and secondarily settings. Accordingly, the tales of this anthology are grouped into 18 categories based on culturally-defined convergence of themes and, to a lesser extent, settings. Why is theme of premier importance here? Theme is a major cultural component of Nigerian oral fiction. In fact, the non-literate person in the community and a typical folktale narrator do not believe that a story without a theme is worth telling. So intrinsically is a folk story connected to theme that every story, not just a fable, is expected to have or inspire some moral at the end of the tale. A tale may not be entertaining and its narrator may not be a good oral performer but, if it teaches a great lesson, the audience may overlook the shortcomings of its narration merely because of the powerful impact of its theme. In the various cultural environments where the tale-collecting research took place, tales are culturally distinguished by their themes. This is why we have placed primary emphasis on themes in categorizing these tales. Moreover, a theme-based categorization gives greater latitude for broad-based grouping of the collected tales. Theme, as applied in deriving the 18 categories, is defined in a narrative sense and, at times, is loosely interchangeable with motif (recurring elements), except in areas where the meaning of the latter is evidently more encompassing. In its usage in categorizing sets of related tales, a thematic concept (covering tales that make various moral statements) is loosely implied. Theme, in this loose sense, could sometimes be as much about what each set of stories is broadly about as about who (in a generic sense) a set of categorized tales is about. Theme as used in the 18 categories does not imply the thematic statement expressly stated in the concluding part of few of the stories, especially the fables. Theme has a conceptually broad application in the naming of these categories, and this is why tales under the same category can make different thematic statements. Setting, as it relates to the categorization of the tales, is a somewhat subordinate parameter and not all the elements that make it an important literary component are implied. The main elements of consideration in grouping the tales were the elements of culture and geography, with the latter overwhelmingly determining the selection of the set of tales placed under “Palace Tales.” Setting is also a contributory factor in the naming of the “Fisherman” and “Hunter” tales categories as the overriding physical setting in which the stories develop is the river (in the case of Fisherman tales) and the forest (in the case of Hunter tales). In the sense of the overall social environment, there is a covert influence of setting in the naming of all the categories, and to help readers familiar with the Nigerian social landscape further appreciate the social context of each tale, we have indicated under every tale the geographic area of the country where it was orally collected. For this purpose, we adopted the country’s six well-known geographic divisions which, in alphabetical order, are as follows: North Central, North East, North West, South East, South South, and South West. The stories in the afore-mentioned collection are featured according to the above alphabetical order. In other words, tales from the North Central come before tales from the North East, and so on. The above are purely geographic areas, not the politically charged geo-political zones under which Nigerian politicians negotiate federal largesse. We avoided using the states of the federation as units of social context in identifying the tales because a state is a political division that may not strictly represent a unique socio-cultural context. For instance, the milieu of each of the states in the South East can, generally speaking and for purposes of fictional setting, be interchanged with that of any other state in the zone. The same can be said of the states of the South West and, to some extent, of the states in each of the other geographic areas. Moreover, states are not fixed or permanent geographic entities as their continued existence, maps and numerical number are subject to unpredictable political events, such as boundary adjustments, creation of new local government areas, creation of new states or adoption of entirely different political units or labels (after all, we used to have provinces and later regions). None of these changeable political situations is likely to affect the relevance of the above six areas as easily identifiable geographic areas and as unmovable indicators of which part of the country any given tale is coming from. Indeed, it has been widely acknowledged that cultural differences are “often geographic (and that) …aspects of the general culture of an area (or a people)…may well be quite independent of political or linguistic boundaries.”21 (Brackets mine) Folktales are very mobile and have been proved to be no respecters of linguistic boundaries. Story lines move across ethnic and linguistic boundaries and variations of the same tale are retold in many languages and climes so that at the end of the day the only thing we can be certain of is where a story is coming from (its geographic source), its linguistic and ethnic origins having being blurred by its spread across different cultures over the years. And it will not be improbable to suggest that the originators of few of these tales might be long dead speakers of those Nigerian languages that have disappeared. Should this be true, how would one ever trace the linguistic origin of such folktales? This is not to say that certain elements of the tale cannot give reasonable clues as to its original source. That is possible but in situations where cultural symbols are interchanged with the transplanting of a tale from one culture to another, the results of such enquiries will at best be academic and inevitably controversial. Even within the same cultural context, it is sometimes difficult to establish which tale is the first to be narrated and which is a variation of it. For instance, which of these similar tales from south-western Nigeria is the original tale: “Tortoise and Buje” (No. 581) and “The Story of Tortoise and Kerebuje” (No. 583)? A similar challenge can be posed regarding “The Lion and the Playful Mouse” (No. 381) and “The Lion and the Mouse” (413), two tales that demonstrate that no one is too strong to need help and no one is too weak to give help. These similarities arise partly because of the nature of folk narration. Since folktales are anonymously authored, each narrator usually introduces his or her own elements within the story. However, as earlier noted, a variation from the original tale is ideally usually created without changing the story’s symbolic characterization and overall cultural idiom. When variations cross cultural boundaries, even this rule can be dispensed with. For instance, “The Boy and the Tiger” (tale No. 21) is well known in many cultural traditions of the world. Its first version dates back to 5th century BC when the Greek fable writer, Aesop, wrote the original tale titled “The Boy Who Cried Wolf,” a story many oral traditions of the world have copied and changed to suit their indigenous cultural references. From this original Aesop tale was derived the English expression, “to cry wolf” (meaning, to give false alarm). The tale has been adapted into songs and films within and outside Europe, one of the best known being the 1973 film, “The Boy Who Cried Werewolf.” Anyone familiar with the original Aesop story will know that this book’s Tale No. 21 is a nigerianized version. Tales can migrate from culture to culture across international, linguistic, and ethnic boundaries and, as they travel, their components are culturally transformed to make them meaningful to new sets of listeners, readers or viewers. Having said this, it should be noted that Aesop’s “The Boy Who Cried Wolf” is a literary fable, not a folk narrative, even though many of his fables were inspired by diverse folk narratives of his time. Typically, folktales are of anonymous authorship. The Aesop narrative variation discussed above is international in nature, but within a nation substantial variations also take place. Sometimes, it may be a variation centred on a given motif. In 2006, the collection of literary narratives, The Stick of Fortune22 was published by Klamidas. It was this editor’s second book of short stories. “The Stick of Fortune,” the title story is woven around the motif of compensatory wealth generation. The story is rooted in Biu folk literature and this editor was not aware such a motif existed elsewhere. In the course of editing this anthology, however, one has discovered that this motif is not peculiar to Biu. The boomerang tale, “The Dog’s Last Compensation” (No. 5), collected from north-central Nigeria, uses the same motif but this is where the similarities end. “The Stick of Fortune” has only human characters while “The Dog’s Last Compensation” has both human and animal characters. The most important distinction lies in the dissimilar dispositions of the protagonists: whereas the main character of “The Stick of Fortune” solely relied on the goodwill of others to increase his wealth, the Dog of “The Dog’s Last Compensation” manipulated his own compensation to his own peril. Parallel motifs are common among these tales. In almost all the geographic areas are found tales that parallel tales from other areas of the country in the key components of plot, characterization and theme. Some common motifs, with two examples per motif, include the jealous elder brother (“The Jealous Elder Brother” [No. 44] and “A Jealous Elder Brother” [No. 473]), the evil junior/senior wife (“The Evil Junior Wife” [Nos. 45] and “The Jealous Senior Wife” [No. 48]), the arrogant beauty (“The Cat without Scars” [No. 50] and “The Girl without Scars” [No. 419]), the talking/singing object (“The Hunter and the Speaking Corn” [No. 256] and “The Singing Lily” [No. 468]). Others are the motifs of journey to the spirit world (“Dancing Competition in the Spirit World” [No. 75] and “The Girl without Ears” [No. 244]), nameless princess (“The King and His Two Daughters” [No. 56] and “Tortoise and the King’s Nameless Daughters” [No. 59]), and magical transformation (“The Farmer’s Dancing Dead Son” [No. 97] and “Kegbim, the Witch Girl” [No. 103]). So pervasive is the spread of similar tales across the geographic areas that we decided that Book 2, being a wide-ranging collection as well as the first of the three selections of the Treasury of Nigerian Tales series, should fly the pan-Nigerian flag and serve simply as a showpiece of tales from Nigeria’s diverse geographic areas. In listing the 18 categories under which the fictional tales were grouped, we need to note that the categorization is not absolute, and that a few tales may seem to fall into two or more categories. This is where identifying the leading character(s) or the central conflict of the tale can help in determining the most appropriate category for such borderline tales. Selected fictional tales which are not placed in Categories 1-17 automatically fall into Category 18 (the Miscellaneous Tales class). Even then, one may still perceive some core elements of one or more of the 17 categories in some stories featured in the miscellaneous group. Although some stories can fit into one or more categories, we have ordered each featured tale into one category. In all, there are 18 categories. Each category of tales makes up a Section of selected tales. Each sectional set of tales is preceded by a brief introductory write-up dubbed “Thematic Snapshot.” This is a three-paragraph informative teaser intended to provoke interest in the type of tales grouped under that section. It is not a preview in the strict sense as no specific tale is analysed. Each “Thematic Snapshot” simply clarifies the meaning and focus of a given category or section. Below, arranged in alphabetical order (with the exception of Miscellaneous Tales), are the 18 categories and the number of tales placed under each category:

Discounting the Miscellaneous Tales category (which is a mixture of diverse tales), the three most dominant thematic categories are the Moralizing, Explanatory, and Marital categories, in that order. Moralizing tales’ premier position adds further credence to the point earlier made, that theme, particularly moral themes, are of prime importance to oral narrators of these tales. Explanatory tales’ second position reflects the fact that all over the world, across cultures, nature and the social environment have always been clothed with mystery and wonder. In earlier times, people tried to explain these mysteries in terms of stories. Such stories as “How the Cockroach Got Its Antenna” (No. 111), “Why the Moon is Partly Dark” (No. 137), “How Burial Started” (No. 138), and “Why the Hen Scatters Her Food Before Eating” (No. 162), are important, in spite of their far-fetched explanations, because they have the tendency of making the narrator’s young listeners to ask further questions, in their private moments, and to seek more credible answers. That marital tales are next in numerical terms points to the strong family values of the communal environment as well as to the social pressures that debase those values. The place of the family as the smallest unit of social organization as well as its critical relevance as the foundational school of communal ethics is somewhat acknowledged by the impressive number of marital tales collected across the country. Someone may ask, why only 18 categories? Well, we could have placed these tales in more or less number of categories, as there is nothing rigid about this categorization. It is merely a convenient way of presenting the tales to the reader, but it is by no means a random grouping as our categorization was informed by the types of tales we gathered during the nationwide tale-collection exercise and by the manner these tales are viewed in their cultural settings. It is necessary to note, at this point, that presenting these tales to the reader in an orderly form is a primary purpose of this collection. This is not a morphological study and, as such, does not require technical classification along the line envisioned by the Aarne-Thompson (AT) index23 of 1928 and its supposedly internationalized update, the Aarne-Thompson-Uther classification (ATU) index24 of 2004. And we may also observe that even with Hans-Jörg Uther’s admission of some international tales left out in the AT index, folk narratives from African traditions, including narratives from Nigeria and most of black Africa, were not included in that taxonomical exercise. In spite of its consideration of tales from some foreign traditions in arriving at the numbers ascribed to tale types and motif types, the ATU taxonomy and the earlier AT model remain basically the same – an analytical tool which may be sufficient for Western oral tradition but very inadequate for Nigeria’s folk literature and the oral literatures of other African tradtions. As Ashliman has pointed out, “The Aarne–Thompson system catalogues some 2500 basic plots from which, for countless generations, European and Near Eastern storytellers have built their tales.”25 Stith Thompson’s own 1955 Motif-Index of Folk-Literature, while generally liberal, had similar shortcomings. Uther’s 2004 attempt at internationalizing the AT taxonomy did not result into a universally acceptable classification number system. We did not set out to embark on a systemic numbering of these tales in the manner envisaged by the Aarne-Thompson-Uther index. Our aim in A Selection of Nigerian Folktales: Themes and Settings is to present in English diverse fictional narratives of Nigeria. And this we have done. Scholars interested in folkloristic morphology will find in these narratives some raw materials for such structural studies.

In closing, it is good to note that the fact that folktales are transmitted from generation to generation by oral tradition does not mean the art of creating folk stories ended with our forebears. It appears that in non-literate societies, every generation not only transmits to the next generation its heritage of tales but also tells its own fresh tales which, generations later, would seem as old as any other. There are modern folk tales and some of them can be identified by certain features which give away their period of composition. Two of the most outstanding of such features are character and place names. Even in this collection, modern folktales abound. Tales such as “The Hyena, the He-goat and the Squirrel” (No.19), “Derek and Erik” (No. 449), “Janet, the Stubborn Girl” (No. 462), “The Singing Lily” (468), “Hyena and Spider’s Business” (No. 621), and “Musa and Monster” (No. 625) can roughly be dated within the last 50 to 100 years. They are by no means pre-historic tales as we can rightly guess the relatively modern epoch when their first anonymous authors narrated the tales. Let us enquire into their probable dates of first narration. “Derek and Erik” (No. 449), “Janet, the Stubborn Girl” (No. 462) and “Musa and the Monster” (No. 625) are tales narrated after the advent of Christianity and Islam. The names of the characters (Derek, Erik, Janet and Musa) give us adequate clues, just as the “Islamic school” mentioned in “The Hyena, the He-goat and the Squirrel” (No.19) tells us that this is not a tale told at a period of pre-Islamic experience in Nigeria. But there are other indicators beyond character and place names. The approximate date of some of the stories can be known through the characters’ occupations and the kind of money used in business transactions. These two can give several clues as the age-old vocations (such as hunting and fishing) are not really many and the history of modern vocations and hobbies is well-documented. Equally properly documented is the history of money. And so we can use available records to trace with a high level of accuracy the period of the first narration of some of these modern folktales. Let us, for example, use the occupation clue to trace the period one of the tales in this collection, “The Singing Lily” (468) was first narrated. “The Singing Lily” gives us an occupational clue in the second sentence of the tale: “Their parents loved gardening.” As an activity of “growing and maintaining the garden”26 (the garden defined as “a planned space, usually outdoors, set aside for the display, cultivation, and enjoyment of plants and other forms of nature”27) gardening has recorded history. Within Africa, the first gardens were reputed to have been built by the Egyptians who were conquered by the Romans in 30 BC.28 There is no evidence that indicates that gardening, in the sense implied in “The Singing Lily,” was a traditional practice of any of Nigeria’s ethnic groups or that the Egyptians, Africa’s earliest gardeners, introduced that concept into Nigeria before the entire area now known as Nigeria was colonized between 1861 (when Lagos was annexed) and 1898 (when the North was secured for the British).29 As for the “Lily” flower of this tale’s title, available records show that it is not indigenous to Nigeria. According to a credible source, “There are between 80 to 100 species of lilies (Liliaceae), and most are native to the Northern Hemisphere in Asia, Europe and North America.”30 Since the Europeans who colonized Nigeria were the British, it could be said that the British most likely introduced the Lily flower into Nigeria. So, if we take into consideration the more inclusive date of 1898, the new folktale, “The Singing Lily,” cannot be more than 117 years. If we make room for the years it took the Nigerian Lily to spread across the communities to the point of being a folk reference, the date of the first narration of the “The Singing Lily” is probably less than 100 years – maybe under 50 years. Such a historically-derived method of dating can be applied using the currency indication in a tale. And we can illustrate this with the tale, “Hyena and Spider’s Business” (No. 621). Here is the opening paragraph of the tale: One day, a greedy spider bought a knife and a basket. Each of the two items cost him six pence. He needed manure and went to his neighbour’s house to see if he could give him some. His neighbour asked him to go to the backyard and fetch as much as he wanted. When he went there, he brought out his knife, slaughtered a goat, threw it inside his basket and left. Mention is made of a specific currency and amount in the second sentence; there we learn that the spider’s newly-bought items cost him “six pence” each. “Six pence” ceased to be a legal tender in Nigeria on January 1, 1973, when the currency units, naira and kobo, were introduced to replace pounds, shillings and pence. Since folk narrators like to communicate to their audience using conversational language and the most current forms of expression, we can say that an oral narrator creating this story after 1973 was likely to have used “kobo,” not “pence,” in indicating the cost of the spider’s items. This is a story orally narrated and translated into English in 2014; yet, the narrator used “pence” rather than “kobo,” unconsciously indicating that the tale was first narrated before the introduction of naira and kobo and was simply orally transmitted to the hearing of the 2014 re-teller. So, we can establish that the earliest narration of “Hyena and Spider’s Business” was in 1972 or a few years earlier. All these enquiries about the date or period of a tale’s first narration are important in that they show that regardless of the general decline in the practice of narrating folktales to children, new folktales are still being created in Nigeria. These modern folktales may not be many, and hopes of having them transmitted to future generations via the oral tradition may seem slim. However, with tales hitherto only orally transmitted now being documented in books such as A Selection of Nigerian Folktales: Themes and Settings, there is hope that no matter how the wind of modernity blows, our folktales may continue to be as enduring and timeless as the moon. There is need to adopt them into modern communication systems such as animations (cartoons) and film/television documentaries.

Endnotes

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||