Global Online Journal of Academic Research (GOJAR), Vol. 3, No. 1, February 2024. https://klamidas.com/gojar-v3n1-2024-04/ |

|||

|

Aspects of Nigerian Myths, Legends and Chronicles By Bukar Usman

Abstract This is an introductory essay on Nigerian myths written by the author to introduce a historic collection of hundreds of Nigerian myths, legends and chronicles collected from different parts of the country and published as an aspect of his massive Treasury of Nigerian Tales (TNT) series. The stories introduced here are all mythic in orientation and include clan or settlement chronicles, tales related to rituals and traditional religious practices, narrations about epochal historical events, origin and cosmic tales, creation tales, tales about legendary heroes and heroines, tales that explain the origin and nature of the world, and tales about the exploits of the gods. This expository essay is divided into the following parts: introduction, definition, functions and features of myth, myth and history, special audience and narrators, classification of Nigerian mythic tales, and conclusion. The collected and discussed mythological tales are 213 in number. Keywords: Nigeria, myths, legends, chronicles 1. Introduction The first two books of the Treasury of Nigerian Tales (TNT) series are collections of fictional tales collected from all over the country under the auspices of the Dr. Bukar Usman Foundation (henceforth, the Foundation). These two books, A Treasury of Nigerian Tales: Themes and Settings1, and People, Animals, Spirits and Objects: Folk Stories of Nigeria2, contain 700 and 1000 folktales respectively. This anthology, the third book of the series, is definitively different. Unlike the first two books of the series, it is a collection of historical or non-fictional tales and consists of myths, clan or settlement chronicles, tales related to rituals and traditional religious practices, narrations about epochal historical events, origin and cosmic tales, creation tales, tales about legendary heroes and heroines, tales that explain the origin and nature of the world, tales about the exploits of the gods and about the Creator Himself. This category of tales is deemed to be factual even when the presumed facts seem too unfounded or too exaggerated to be considered true outside the cultural context of the tales.3 The words, “historical” and “non-fictional,” are italicized above as a way of qualifying their meaning within the scope of this discussion. No body of myths of any known group, region or race is altogether history or non-fiction. Fantasy, delimited by a given cultural context, has always been an aspect of myth. This point is elaborated upon in greater detail below. Another qualification worthy of note concerns the scope of this work. Mythic tales included in this collection are limited to those gathered by field researchers engaged by the aforesaid Foundation. No tale outside those garnered by the collectors engaged by the Foundation was admitted in the two earlier-published collections of the Nigerian Narrative Series. We strictly adhere to the same principle here. Hopefully, this delimitation would give some insight into the nature of oral tales still in vogue across the country in the early decades of this century. However, because narratives selected here strictly emanated from our field research, it is likely that some tales of mythic importance, which were not narrated to our tale collectors, may not have been included here. This is why this editor makes no claim whatsoever that this collection is an exhaustive anthology of the mythology of the over 500 ethnic/language groups of Nigera. This book of tales of direct or indirect mythic relevance should be seen as a subset of the outcome of a nationwide tale-collection exercise put together to stimulate interest in more exhaustive and comparative research in this area. This notwithstanding, key mythological figures of Nigeria, whether captured by our tale-collection field workers or not, are liberally cited in relevant areas of this discussion. Lastly, it is important to point out that the mere incidence of being selected or published here does not invest upon any tale the status of being the official or fixed version of any given myth, chronicle, or event. In the various communities where these tales were collected, the oral narrators were neither pre-selected nor prodded to tell particular tales or preferred variants thereof but were simply left to their own discretion regarding what tales they volunteered to our field researchers. And from narrator to narrator many of the tales varied. To a large extent, the versions published here remain as they were collected in the local languages and translated into English. In editing the tales, steps were taken to ensure that key elements of the transcribed versions were maintained. As a cautionary measure, readers should, however, bear in mind that for any narrative published here, another version or versions of it might exist in their tale-bearing communities. It should be added that most variants only differ on matters of detail. 2. Definition, Functions and Features of Myth Let’s begin our exploration of the mythic tales of this anthology by asking, “What is myth?” Simply put, a myth is a traditional narrative, set in the distant past, which tells a given group of people about supernatural events and personages by which they make sense of their existence and environment or offer explanations for various natural and supernatural occurrences. As such, many mythic tales are about the origin or history of great ancestors, patriarchs, matriarchs, legends, and ancient events; and about why and how some cosmic or natural state of affairs came to be the way they are today. Myth, however, embraces much more than the features highlighted above. Since it is difficult to proffer an all-inclusive definition of myth, it will be helpful to look at the way other scholars have defined or explained the term. Melville and Frances Herskovits offer a more elaborate definition: On another level, we may define myth as those narrative forms that embody a system of symbolized values which in each separate society phrase the philosophy underlying its concepts, ideals and ends, and mark off its culture from all others as a way of life. Myth, in these terms, implies a social acceptance of approved symbols that, by transcending the generations, are at once the instrument of identification with the past and with the continuities of present and future. That is to say, like all manifestations of culture, myths draw their deepest sanctions from the fact that for the individual of a given society they existed before he was born, and that he carries the conviction they will continue after he is dead. Herein lie both the social and psychological importance of mythic symbols.4 The excerpt below, in a simplified way, defines myth as a literary device that has significant functions. According to this viewpoint, Myth is a legendary or a traditional story that usually concerns an event, or a hero, with or without using factual or real explanations, particularly one concerning demigods or deities, and describes some rites, practices and natural phenomenon. Typically, a myth involves historical events and supernatural beings. There are many types of myths such as classic myths, religious myths, and modern myths… Myths exist in every society, as they are basic elements of human culture. The main function of myths is to teach moral lessons and explain historical records…Myths and their mythical symbols lead to creativity in literary works. We can understand a culture more deeply and in a much better way by knowing and appreciating its stories, dreams and myths…Besides literature, myths also play a great role in science, psychology and philosophy.5 You would notice that in our discussion of myths, direct or indirect reference to an identified group – be it clan, ethnic or racial group, nation – is often made. This is because a myth is the property of a given culture, not that of an individual. An author or oral narrator may freely weave a myth into his or her tail but may not impose upon that myth a symbolic meaning which varies very much from that dictated by the myth-bearing culture. A myth is a cultural expression and, as such, must be understood within the context of a given culture. The symbolic values derived from myths are not open to random or personal interpretations but are essentially culturally fixed. To understand the myth, therefore, one would need to understand the originating culture, for the myth is often the ethnographic root of the associated socio-cultural beliefs and practices. In many rural and semi-urban communities in Nigeria, taboos and many social acts are validated in myth. In “The Story of Bode-Ado,” (tale no. 150), for instance, incest is discredited. “The Legend of Ewane, the Drunkard” (no. 152) demonstrates the need to protect the role and person of the social critic. Even the supposedly trite pidgin English saying, “Water no get enemy,” popular among Nigerian groups, can be said to be rooted in such mythic tales as “Friendship of Fire and Rain” (no. 4) and “The Earth and God” (no. 5), which establish the supremacy of water over the other elemental forces. In the realm of ritual and traditional religious practices, mythic symbolism revolves entirely around a given ethno-religious culture. According to Malinowski, ritual is shaped by myth. In his view, an intimate connection exists between the word, the mythos, the sacred takes of a tribe on the one hand, and their ritual acts, their social organization, and their practical activities, on the other.”6 Among others, the following tales of this collection illustrate vital aspects of the above viewpoint: “The Gods Never Lie” (no. 97), “The Son of the Chief of Dagom” (99), “The Sorcerer of Amagbor Kingdom” (no. 101), and “Why the Devil is Superior to Other Deities” (no. 103). This connection between myth and ritual emphasized by Malinowski sometimes puts on the reader the responsibility of acquainting themselves with the mythology behind a given mythic tale. For the reader who is content with whatever surface entertainment they may derive from a story, this may not be necessary. But a committed reader, searching for deeper meanings, would need to access the mythic background behind the tale. In this book, the reader who wants to fully appreciate the import of some of the tales collected from the South-Western part of the country should have a basic understanding of the pantheon of Yoruba gods and the significance of some of the rituals engaged in by traditional devotees. Such cultural understanding would help one better appreciate, among others, tale nos. 103 – 110. For an informed introduction to African religious myths and rituals, John S. Mbiti’s book, Introduction to African Religion (second edition) would be a good read. According to Mbiti, In many African societies it is told in myths that at the beginning God and man were in very close contact, and that the heavens (or sky) and the earth were united. For various reasons this link was broken and God became more distant from the people. But through worship man is able to restore that original link to a certain extent.7 This unity of religion and myth is represented beautifully in “The Earth and the Sky” (tale no. 1) and reflects a basic belief in humankind’s fall from grace at the beginning of time, a popular tenet of many orthodox religions. The history of this fall from grace to sin is conveyed in religious simplicity in the following passage taken from the tale: In the beginning of time, when God created the earth and the sky, the sky was so close that the hands of the people living on earth touched it without much effort. The sky had a lot of fruits which human beings plucked and ate at will. Human beings had no problem at all in getting food to eat because the sky supplied them with food in abundance. But, at a point, people of the earth made the sky to get angry because of their greed. They would pack food so recklessly that they went home with a lot more than they could eat. The rest was wasted and dumped in the dung-hill. … The sky could not control his anger. He was convinced that human beings were greedy beyond redemption. He had to teach them a lesson they would live with forever. Gradually, the sky began to move upwards. Human beings stretched their arms at full-length, but they could not reach the sky. He moved so far up that human beings could only see it in the distance high up there. And they lost the chance of enjoying the creator’s easy providence. This motif of punitive separation between the sky (God) and the earth (human beings) also motivated “The Birth of the Seasons” (tale no. 13) and explains “Why the Sky is Higher than Land” (no. 14). As Mbiti noted, something was needed to restore the above state of separation between God and the human beings He created. The latter identified worship as a remedial measure (“through worship man is able to restore that original link to a certain extent”), hence the worship of deities and ancestral spirits in many traditional communities. Some of the major ways traditionalists approach God through are prayers, offerings and sacrifices. And God is approached by different ethnic groups of Nigeria through a number of deities and ancestral spirits. Many of the myths associated with the culture of Nigeria spring from the worship or veneration of these deities and spirits. This excerpt from Toyin Falola’s book aptly captures some aspects of this customary reality as they manifest among some Nigerian groups: The Yoruba have constructed a hierarchy of spiritual forces…God is the supreme deity with the ultimate power, the creator of the universe, the final judge. Below God is a plethora of gods and goddesses, the orisa. There is a god for most material items, and nonmaterial ideas; for instance, Osun and Oya are river goddesses, Sango is the god of thunder, Ogun is the god of iron. There are many major Gods, such as Ogun, and there are many local ones below them, associated with lineages, towns and geographical features… Gods are also associated with occupations… … The Igbo believe in Chukwu, the Supreme God, who has various messengers such as the sun, sky and earth… Land is venerated through a system of religious beliefs known as ala, which rewards and punishes people according to their behaviour… The Igbo also believe in the power of ancestors, as do many other Nigerian groups. … For the Kalabari, there are two forms of existence. The first is oje, the material world, the physical reality that can be seen. The second and more important is the spiritual order, known as teme. Teme is divided into layers of hierachies of spiritual forces. On the very top are the creation gods, followed by the lesser gods including ancestors (“water people”) and local heroes.8 Local heroes or legends are generally venerated. One of the most outstanding of such legends is the Ijo’s Ozidi, the hero of the Ozidi saga believed to have been revealed to the Tarakiri clan’s traditional high priest. The Ozidi saga is an outstanding epic whose summary below is justified by the insight it gives into the stylistic pattern of such traditional epics. The Ozidi saga follows the pattern of other epics: A child is born following the death of his father. He embarks on a quest, during which he has a string of adventures, undergoes tests, and performs great feats of magic and strength. With the assistance of a female relative, he is triumphant and establishes his people. Ozidi was the son of a general who died before Ozidi was born, murdered by treacherous colleagues. The Ijo believe that a violent, unhappy death such as that prevents a dead man from joining his ancestors. It is the obligation of his heirs to restore the man’s honor. This was Ozidi’s quest: to call home his father from the place where the murdered man’s body was unceremoniously dumped and to restore him to his proper place. On his quest, Ozidi was guided by his grand-mother, Oreame, a supernatural being who was in charge of his fate. In keeping with the adventures of epic heroes, Ozidi engaged in battle with all manner of humans and monsters, always triumphant because the gods—including the Supreme God, Tamara—were with him.9 Not all mythic heroes are male. Inikpi, the great legendary figure of the Igala, who sacrificed her life to save the Igala nation, was a princess. Hers was not a suicidal mission but a response to the unusual demands of the ancestors that the king should let her daughter be buried alive in order to avert a devastating defeat of the Igala people by an enemy kingdom. Other heroes, particularly those who began as founders of traditional dynasties, such as the Hausa’s Bayajida, the Yoruba’s Oduduwa, and the Babur/Bura’s Yamtarawala, have since been transformed into symbols of religious and political power. The tale, “How Yamah and Amaha Kingdoms were Founded” (no. 90) indicates that political exigencies, rather than some decrees from the gods, could provoke the founding of new dynasties which future generations are likely to legitimize through myths. Myths therefore could also function as the ruling class’s means of legitimizing religious and political privileges. Some of the tales of this collection highlighting the worship of deities by different ethnic/linguistic groups in Nigeria include “The History of the Worship of Tere in Edeland” (no. 53), “Why It is a Taboo in the Ere Alako’s Family to Eat Python” (no. 77), and “The Origin of Tubuog’s Worship of the Moon” (no. 85). Aside from being used to explain the origin of things, myths also serve as tools for explaining why and how things function (examples would include tale nos. 76-78). Often, the latter role is served in comparative terms, as could be seen in such tales as “Why the Sun Shines Brighter than the Moon” (no. 24), “Why Lightning Precedes Thunder Blast” (no. 25), and “Why the Devil is Superior to Other Deities” (no. 103). Mythic tales can also serve explanatory purposes by the manner in which they are used to explain how certain unusual things came to be. Such mythic explanations enable us to ponder about “How Foolish People were Created” (tale no. 30), “How Mermaids Became Half-Fish, Half-Human” (no. 88), and “How Àlàbá the Pawn Was Killed By His Mouth” (no. 179). Underlying all the functions of myth highlighted above is the given group’s belief or presumption that all of the above mythic phenomena spring from history, not fantasy. We will dwell on myth and history in the next section of this essay. All we may note here are some of those tales whose manner of presentation position them as pure history. They include “The History of Oyo and Oro Celebration” (no. 39), “The History of the Blacksmith from Heaven” (no. 44), and “The History of Affor People.” Other tales narrated in similar tone are those centred on long-standing compounds. Illustrious families promote and sustain their socio-economic or political relevance by telling and retelling their glorious “history.” Some of the tales fulfilling this function in this collection include “The History of Wárí Compound” (no. 41), “How Pere Compound Got Its Home” (no. 52) and “The History of Iyagba Compound.” 3. Myth and History The difficulty often encountered by those who may wish to separate real history from myth is the belief by the concerned community or group that their pet myth is as factual as any historical narration. Even myths featuring supernatural beings, or animals playing the role of human beings, are deemed true by such groups. How should a scholar deal with this kind of confusion? Generally speaking, and as this editor had observed in his book, A History of Biu10, the above situation is inevitable whenever anyone conducting a research find themselves in the domain of oral tradition. While the mythologist may be comfortable here, the historian, who must verify and date his or her facts, is likely to raise questions. Unfortunately, when dealing with “the origin of nationalities, clans, domains, and long-standing traditional institutions…especially when dealing with the genesis of homogenous groups, dynasties and old civilizations,”11 the historian, anthropologist, and literary analyst cannot avoid the “twilight zone between folklore and history.”12 Myth thrives within this twilight zone; yet, it cannot be ignored because of the important roles, some of which were mentioned above, it plays in enriching art and stabilizing society. The historian, in this writer’s view, appears to be the one more concerned about the need to separate fact from fantasy. I felt that need while working on A History of Biu. And I tried my best to resolve the problem, hopefully to a large extent, by cross-checking oral tradition against written history and those ethnological data which shed light on the issues under consideration. As for students of myth, their emphasis could be on the use and significance of the myth within the context of the relevant culture. What this means is that their concern with history may not go beyond “those facets of the culture or history which throw into special relief certain customary usages emphasized in the narratives, or clarify the meaning of certain historical allusions.”13 4. Special Audience and Narrators Unlike the ordinary folktale whose audience is the common folk, mostly children, historical tales are generally targeted at an adult or specialized audience. And not everyone can narrate a number of these tales. Some mythic tales are for the ears of the menfolk or professional groups while others must only be narrated by diviners or griots commissioned by the king. These are some of the features which separate historical tales from typical moonlight tales. The relevance of historical tales does not necessarily lie on the morals of the tale but, rather, on their historical data, ritualistic value, philosophy, special knowledge or social enquiry. In general, they are narrated by elderly males to adult males of a particular family, professional or religious group. Tales about natural phenomena, history of ethnic groups, and the origin and exploits of illustrious ancestors fall into this general category. To narrate some historical tales, one would need to have skill, not just age, on his side. Some tales are narrated at a great risk and cost to the narrator. The king’s griot, whose duty it is to memorize and recall, during his daily chant, the names and great deeds of past rulers, and the momentous events of the ethnic group’s past, must not make a mistake. In the past, some griots are said to have lost their lives because they forgot or misrepresented a royal act. This is why such recitatives are composed and delivered by professional verse-makers. Besides, not everyone can compose such heroic verses or narrations as they require the use of appropriate imagery and proverbial expressions, which only the most skilful composers endowed with exceptional retentive memory can handle. Moreover, many historical tales are not carelessly narrated since they are deemed to be factual and sacred; so, in spite of the existence of variants in some quarters, there are official versions of genealogical tales. Divination chants also command similar requirements in composition and delivery. Infact, for mythological settings with formal systems of divination, such as the Ifa divination system of the Yoruba, only the babalawo is deemed skilful enough to chant and interprete divination verses. Among some groups in Nigeria, the traditional high priest and custodian of the main shrine serves as the sole narrator of any mythic communication from the spirit world. Sacred narratives or chants are accompanied by idiomatic expressions and other forms of indirect use of language. “Odu Ologbon Meji” (tale no. 106) begins with such expressions: No wise man can hold water at the edge of his wrapper. The wise one does not know how much sound we have on earth. No wanderer knows where the world ends. A sharp knife cannot carve its own handle. It takes experience and familiarization with historical allusions to make appropriate sense of such expressions. Praise songs, such as this Sango’s praise taken from tale no. 57, are sometimes needed to enliven an oracular narration: Sàngó Olúkòso, Arẹmu Ogun The brave one and the husband of Oya, An expanding fire on the roof Èbìtì fọwọ bẹhin soro Breaker and cracker of walls Breaker of walls, replacing them with ridges Fire escaping from the eyes, the mouth and on the roof Sàngó Olufiran the King of Kòso The deity whom Timi seeks in absentia Sàngó Tìmí who sees all things This is one more reason why only experienced devotees can purposefully serve as narrators in this purely traditional area. Composition and narration of tales dedicated to trade or professional groups is, however, more liberally restricted. Professional groups share mythic tales related to their profession within their respective groups. Tales about blacksmithing, for example, are usually narrated by blacksmiths within their group or among those who share some common interest with them. In traditional societies, the nature and demands of one’s trade or skill often compels one to associate with those engaged in similar endeavour. And in such gatherings, particularly when assembled for the prime purpose of worshipping the god associated with their trade, tales of common interest to the group are shared by members of the group during moments of social interaction. For hunters, tales of such nature in this collection would include “The Day Death was about to Die” (no. 173) and “The Hunter’s Supremacy over the Deer” (no. 180). 5. Classification of the Mythic Tales Given the overwhelmingly mythological nature of the tales of this collection, classifying them into appropriate sections posed some challenges. Sometimes, one tale may bear the characteristics of tales placed in one or two other sub-groups. This may not be surprising as many of the tales have something to do with gods/ancestors or the cosmic order they have shaped. In spite of the overlapping nature of the tales, they have been grouped according to the perceived dominant concern or objective of each set of tales (Groups 1-4) or their unique contribution to the assortment of the set (Group 5). The name given to each group of tales gives a clear hint of the organizing principle adopted in classifying the group. Under each of these groups, listed below, further explanations are given to guide the reader. Here, then, are the 5 classes:

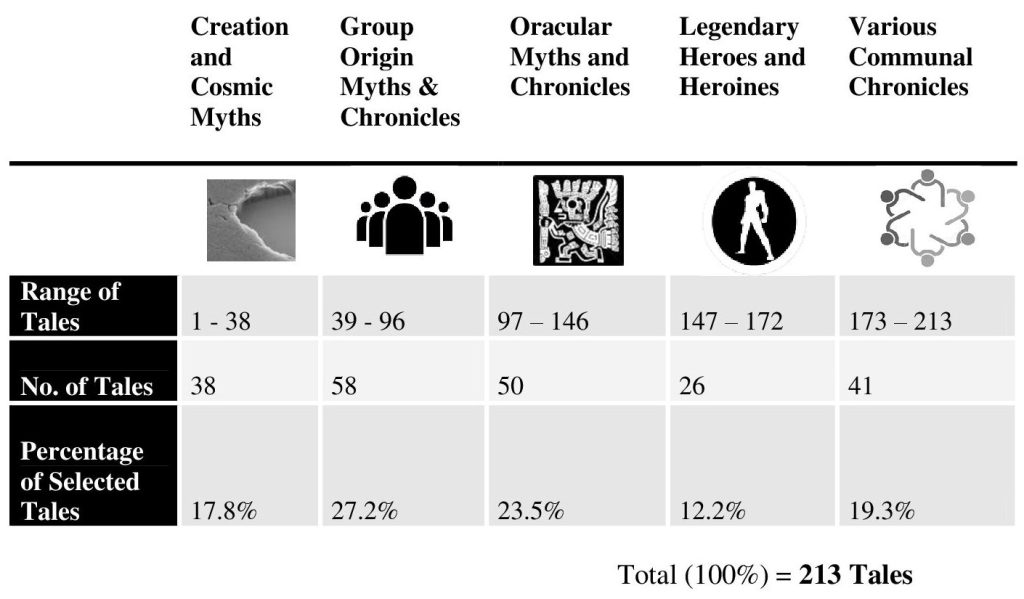

Below is a tabular reflection of the number of tales featured in each of the above classes.

It is good to note that this statistical representation, as it concerns the number of tales featured in each class, does not necessarily indicate any preferential decision on the part of the editor. These selections simply reflect the number and nature of mythic tales our tale-collectors were able to gather from our various communities. Suffice it to say that the bulk of the tales readily collected from our folks across the country were mostly the common fictional folktale type – and these were featured in the first two books of the Treasury of Nigerian Tales series. 6. Conclusion As we can see from the above submissions, mythic tales offer traditional folks of Nigeria creative ways of responding to perennial problems of existence which have challenged mankind in general across the ages. They are artistically, socially and spiritual important and both the literate and non-literate members of many communities that these tales or their practical implications seriously. The advancement of science and technology has solved a lot of socio-economic problems, but still many questions remain unanswered. Questions about life and death, faith and destiny, may never be convincingly answered without recourse to some form of belief in a higher power. Since most people seem incapable of understanding an abstract Supreme Being, their need for identification with ancestors and gods they can see and relate to is, from their viewpoint, understandable. What is of interet to us, as we shall see in the mythic tales themselves, is the capacity of the human imagination to create or re-enact stories that have gone through many generations but still provide powerful belief systems which help people to grapple with the many challenges of life. Endnotes

|

|||

|