Journal of Education, Humanities, Management and Social Sciences (JEHMSS), Vol. 2, No. 1, January 2024. https://klamidas.com/jehmss-v2n1-2024-03/ |

||||

|

Charles Peirce’s Theory of Enquiry: An Epistemological Analysis Innocent Ngangah

Abstract This epistemological analysis posits that Charles Peirce’s pragmatism is not confined to the “determination of the meaning of terms” but is also, and more fundamentally, a theory and tool of enquiry. To substantiate this view and distinguish pragmatism from some dominant antithetical viewpoints that predate it, the paper broadly explores the origin, unique features, and practical relevance of Peirce’s classical brand. The study concludes by pointing out the inherent contradictions in the views of John Dewey, Peirce’s contemporary and the first notable philosopher to query the heuristic value of Peirce’s pragmatism. Keywords: Charles Peirce, pragmatism, epistemology, meaning 1. Genesis of Pragmatism Charles Sanders Peirce (1839 – 1914) is generally regarded as the father of pragmatism although William James, his contemporary and one of the major philosophers he influenced, was the first to use the term in print. A polymathic sage, Peirce’s interests, thoughts and practical engagements cut across the fields of science, mathematics, semiotics, and philosophy. He enriched philosophy, especially logic, with the principles he derived from science. So influential were his contributions to philosophy that, although he held very brief academic employment and largely lived a reclusive life, he was universally credited with founding the United States only home-spurn philosophical tradition, the pragmatic movement. Peirce wrote and published many scientific articles, including the two seminal works of his “Illustrations of the Logic of Science” series, namely, “The Fixation of Belief” and “How to Make Our Ideas Clear”. James regarded these two publications as the foundational pillars of pragmatism. Peirce published no book during his lifetime. These two theoretical foundations, upon which James, Dewey and other proponents of the movement have built, form our primary texts of reference in this dissertation. Hundreds of his manuscripts were unpublished at the time of his death in 1914, and these have been gathered into six volumes by Harvard University and published as Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce (Hartshorne and Weiss 1974), thenceforth the Collected Papers or simply CP. The fifth volume is dedicated to his papers on pragmaticism. Pragmatism was first proposed by Peirce as a principle and account of meaning in 1870 but his formulation was published later in his earlier-mentioned article, “How to Make Your Ideas Clear”. The key point of this article is that action validates concept – there must be a practical end to any concept or mental object before it can become meaningful. Otherwise, such an object or concept is meaningless. In other words, the extent to which a proposition or ideology can satisfactorily work in practice is the extent of its theoretical validity. In effect, impractical ideas should not be accepted as valid ideas. Peirce’s thesis spurned a cross-continental movement after his more visible contemporary and Harvard professor, William James, took the idea to the centre stage of scholarly discourse in an address he delivered at the University of California, Berkeley, in 1894. In that paper, “Philosophical Conceptions and Practical Results,” James became the first person to use the term “pragmatism” in print but insisted that the term had been coined decades earlier by his close friend and reclusive philosopher, Charles Peirce. Etymologically, “pragmatism” is traced to the Greek words, πρᾶγμα, which stands for pragma (“a thing, a fact”), and to πράσσω or prassō (“to pass over, to practise, to achieve”). In view of Peirce’s elevation of practice as the validating end of theory, “pragmatism” is a very apt term for his formulation, and it is perhaps this linkage which has made “pragmaticism,” his later-preferred term, very rarely used by others. 2. Real Doubt versus Cartesian Doubt The nucleus of Peirce’s pragmatic philosophy and its primary distinguishing factor is his position regarding the role and nature of doubt as a trigger of philosophical, and indeed all, enquiries. He was not the first to assign a philosophical role to doubt. Earlier philosophers, notably René Descartes (1596-1650), had recognized doubt or doubting as a mental pre-requisite for a systematic investigation of truth. The fundamental difference Peirce made was his anti-Cartesian re-definition of the nature of doubt. Cartesian doubt, as a methodological process, questions already-held beliefs in order to arrive at beliefs one could be certain about. In other words, Descartes’ position is that one should be skeptical about one’s beliefs, thoughts and ideas as a systematic route towards determining which of them may be accepted as genuine truth. Cartesian skepticism amounts to a universal questioning of all beliefs. To help us distinguish Cartesian from Peircian doubt (discussed below), let us compress Descartes’ four-step technique into the following basic Chevron process:

Note that “true beliefs,” sifted after systematic doubting of “all beliefs,” are still arrowed towards further enquiry. In the Cartesian model, there is no absolute truth. Descartes’ methodological skepticism questions all beliefs in order to arrive at basic or true beliefs which themselves are subject to further doubt in the service of further knowledge. This model dominated Western philosophical thought before Peirce’s seminal articles, “The Fixation of Belief” and “How to Make Our Ideas Clear” made the distinction between verbal or hyperbolic doubt and real doubt and placed belief at the end of every enquiry rather than at its beginning. Peirce argued that enquiry should depend on real doubt, not on verbal disputations over belief. As he put it, “the action of thought is excited by the irritation of doubt, and ceases when belief is attained; so that the production of belief is the sole function of thought.” (Peirce 1878:286-302) For Peirce, belief and doubt do not necessarily have religious connotation; rather, he uses both terms “to designate the starting of any question, no matter how small or how great, and the resolution of it.” (Peirce 1878:286-302) While Descartes sees belief as the instigator of doubt, Peirce sees doubt as the producer of belief. This Peircean view is energized by these three properties Peirce ascribes to belief: First, it is something that we are aware of; second, it appeases the irritation of doubt; and, third, it involves the establishment in our nature of a rule of action, or, say for short, a habit. As it appeases the irritation of doubt, which is the motive for thinking, thought relaxes, and comes to rest for a moment when belief is reached. (Peirce 1878:286-302) Putting Peirce’s position in comparative relief, we may represent his methodological process of enquiry with the same Chevron illustration we had earlier used in relation to Descartes. From the foregoing, we may represent Peirce’s own Chevron graphic thus:

Although Peirce avers that “the action of thought is excited by the irritation of doubt, and ceases when belief is attained,” (Peirce 1878:286-302) this cessation is only temporal, as belief sways future thinking, and not a permanent state of rest. His “thought at rest” is thus, in a sense, thought on recess. Peirce’s explanation: since belief is a rule for action, the application of which involves further doubt and further thought, at the same time that it is a stopping-place, it is also a new starting-place for thought. That is why I have permitted myself to call it thought at rest, although thought is essentially an action. (Peirce 1878:286-302) Compare this with the Cartesian endless questioning of all beliefs and it would appear that both methodologies regard thought as a continuous exercise. However, there is a remarkable difference here. For Peirce, “The final upshot of thinking is the exercise of volition” (Peirce 1878:286-302) while for Descartes, it is the exercise of doubt. This brings us to the distinction between Cartesian doubt and Peircean doubt. Descartes’ view is that all beliefs which cannot be justified by logic should be subject to doubt. Of interest here is his use of himself to illustrate this view. In his Principles of Philosophy (first published in Latin in 1644), he subjected himself to doubt, thereby doubting his very existence, but arrived at his well-known philosophical proposition, “Cogito ergo sum,” Latin for “I think, therefore I am.” In other words, according to Descartes, we “cannot doubt of our existence while we doubt…” (Stehr and Grundmann, 2005) Doubt for Descartes is an exploratory mental exercise, an intangible game of logic. For Peirce, doubt is a living reality: “…the mere putting of a proposition into the interrogative form does not stimulate the mind to any struggle after belief. There must be a real and living doubt, and without this all discussion is idle.” (Peirce 1878:286-302) Peirce, thus, brought doubt down to earth. Doubt in Peirce’s philosophy is thought that generates a distinct belief or cause of action; it is conceptually result-driven and, in effect, tangible or real. As Pierce put it, “…every stimulus to action is derived from perception; …every purpose of action is to produce some sensible result. Thus, we come down to what is tangible and conceivably practical, as the root of every real distinction of thought…” (Peirce 1878:286-302) If two doubts cannot be distinguished in this respect, the presumed differences between them are only verbal or sophistic and in practical terms non-existent. According to Peirce, “Our idea of anything is our idea of its sensible effects; and if we fancy that we have any other we deceive ourselves and mistake a mere sensation accompanying the thought for a part of the thought itself.” (Peirce 1878:286-302) For Descartes, the immediate use of thinking is logic; for Peirce, the immediate use of thinking is to generate a practical effect or a cause of action. Herein lies the fundamental difference between both philosophers. Peirce’s action-oriented doubt gave rise to his pragmatism, which, in part, resulted from his further thinking on the thoughts of Alexander Bain. 3. Influence of Alexander Bain on Peirce’s Pragmatism Charles Peirce’s most significant remote influence was his father, Benjamin Peirce, an eminent Harvard mathematics professor and astronomer, a man who contributed immensely to the development of American sciences in the 19th century. Charles Peirce was also influenced by earlier philosophers, notably Whately and Kant. However, Alexander Bain was the man who exerted the single most significant immediate influence on Peirce as far as his pragmatic philosophy is concerned. Peirce never met Alexander Bain (1818-1903), the Scottish philosopher, psychologist, mathematician and scientist, but was greatly awed by his ideas, particularly his definition of belief as “that upon which a man is prepared to act.” When Peirce encountered this definition through Nicholas St. John Green, a fellow member of The Metaphysical Club, it illuminated his, as at then, crystallizing thoughts on the nature of doubt and belief. Peirce openly acknowledged Bain’s powerful influence and its direct role in the formulation of pragmatism. Understanding what Bain had said, which Peirce found so influential, is critical in understanding Peirce’s pragmatism. The core of Peirce’s pragmatism is that action is an inseparable component of belief. In other words, what you are not disposed to act upon is what you do not believe, for belief is a disposition to act. This idea came from Bain, the founder of the influential journal, Mind, and the European philosopher Green and the others often talked about during the meetings of The Metaphysical Club. In particular, he [Nicholas St. John Green] often urged the importance of applying Bain’s definition of belief, as “that upon which a man is prepared to act.” From this definition, pragmatism is scarce more than a corollary; so that I am disposed to think of him as the grandfather of pragmatism. (Peirce 1907) Within the context of his time, Bain’s definition was revolutionary. Even today, that definition remains practically relevant. In his Emotions and the Will, Bain expatiated further on this view of belief Peirce found so thrilling: It remains to consider the line of demarcation between belief and mere conceptions involving no belief – there being instances where the one seems to shade into the other. It seems to me impossible to draw this line without referring to action, as the only test, and the essential import of the state of conviction even in cases the farthest removed in appearance from any actions of ours, there is no other criterion. (Bain 1859:595) Before Bain and Peirce, belief was generally regarded as an “occurent” thing – a 14th century notion that regarded it as something that occurs in the mind without a necessary relationship with or validation in reality. Hume’s definition of belief was typical of this. According to Engel, Hume defined belief as “the particular vividness of an idea in the mind”. (Engel 2016) Cardinal Newman also shared the view that belief was a mere mental affirmation. This remained a dominant view whose decline could partly be traced to Alexander Bain’s 1859 treatise on the subject. Exploring from his background in physiology and psychology, Bain sowed the seed of correlation between thought and action when he wrote: It will be readily admitted that the state of mind called belief is, in many cases, a concomittant of our activity. But I mean to go farther than this, and to affirm that belief has no meaning except in reference to our actions; the essence, or import of it is such as to place it under the region of the will. (Bain 1859:568) Bain’s powerful insights, such as “belief has no meaning except in reference to our actions” and belief is “that which a man is prepared to act upon” became mental catalysts that stirred Peirce’s genius and led him to formulate pragmatism in 1873. 4. Peirce’s Theory of Enquiry Charles Peirce’s theory of enquiry is sketched out in his The Fixation of Belief, the first of his two major texts about the topic. Here, we shall extrapolate four key areas of that work which altogether give a fair picture of Peirce’s theory and process of enquiry. To lead up to what the role of enquiry should be, in Peirce’s point of view, we will be examining the object of reasoning, the place of doubt and belief in enquiry, and methods of fixing belief. The latter is uniquely important since Peirce holds that the aim of all enquiry is the fixation of belief. a. Object of Reasoning Peirce began his The Fixation of Belief by giving us an overview of the march of knowledge from the medieval times when whoever was in authority defined knowledge or imposed his own brand of reasoning on everyone under his dominion. That knowledge emanated from subjective experience was the taunted notion but Francis Bacon in his Novum Organum argued that experience should be subjected to open verification. Even “scientists” who were mostly chemists relied on interior experience. The chemist, Laviosier, broke away from this, and ushered in a tradition that relied on calculated findings: The old chemist’s maxim had been, “Lege, lege, lege, labora, ora, et relege.” (Latin for “Read, read, read, work, pray, and read again.”) Lavoisier’s method was not to read and pray, but to dream that some long and complicated chemical process would have a certain effect, to put it into practice with dull patience, after its inevitable failure, to dream that with some modification it would have another result, and to end by publishing the last dream as a fact: his way was to carry his mind into his laboratory. (Peirce 1877:1-15, brackets mine) Lavoisier shifted the emphasis from the manipulation of words to the manipulation of substances. Lavoisier’s physical experimentation wetted the ground for Charles Darwin’s studies in molecular movements, which he used to clarify his biological variation theory. Against this historical background, Peirce urges that we should not form beliefs that cannot be logically defended, even when we feel such beliefs to be valid. Valid reasoning is determined via validly-reasoned principles. According to him, The object of reasoning is to find out, from the consideration of what we already know, something else which we do not know. Consequently, reasoning is good if it be such as to give a true conclusion from true premises, and not otherwise. Thus, the question of validity is purely one of fact and not of thinking. A being the facts stated in the premises and B being that concluded, the question is, whether these facts are really so related that if A were B would generally be. If so, the inference is valid; if not, not. It is not in the least the question whether, when the premises are accepted by the mind, we feel an impulse to accept the conclusion also. (Peirce 1877) b. The Place of Doubt and Belief in Enquiry According to Peirce, doubt is the driving force of enquiry while belief is its destination. Doubt and belief are, thus, beneficial but differ in three respects. One, “our beliefs guide our desires and shape our actions.” (Peirce 1877) Our doubts don’t. Two, the sensation of belief establishes habit: the sensation of doubt questions habit, thereby triggering enquiry. Three, doubt dissatisfies while belief satisfies: Doubt is an uneasy and dissatisfied state from which we struggle to free ourselves and pass into the state of belief; while the latter is a calm and satisfactory state which we do not wish to avoid, or to change to a belief in anything else. On the contrary, we cling tenaciously, not merely to believing, but to believing just what we do believe. (Peirce 1877). And the proof of what we do believe is the action it leads us to take, for “the whole function of thought is to produce habits of action.” (Peirce 1878) In this context, not only present habits matter, would-be habits also matter: “…the identity of a habit depends on how it might lead us to act, not merely under such circumstances as are likely to arise, but under such as might possibly occur, no matter how improbable they may be.” (Peirce 1878) In other words, practice distinguishes meaning, whether such practice takes place in the present or the future. Once there is a possibility or potential of difference in practice, two ideas, no matter how seemingly similar, amount to separate ideas. If there is no clear distinction in the practice they produce, no two ideas, even if so regarded, are really different. Insisting that “the settlement of opinion” is the “sole object” of enquiry, Peirce posits that as soon as a firm belief is reached we are entirely satisfied irrespective of the veracity of the opinion. The important point being made here is that belief is not necessarily about something being true but about its acceptance as truth with the evidence of practical effect on those who so believe: …the sole object of inquiry is the settlement of opinion. We may fancy that this is not enough for us, and that we seek, not merely an opinion, but a true opinion. But put this fancy to the test, and it proves groundless; for as soon as a firm belief is reached we are entirely satisfied, whether the belief be true or false. And it is clear that nothing out of the sphere of our knowledge can be our object, for nothing which does not affect the mind can be the motive for mental effort. The most that can be maintained is, that we seek for a belief that we shall think to be true… That the settlement of opinion is the sole end of inquiry is a very important proposition. It sweeps away, at once, various vague and erroneous conceptions of proof. (Peirce 1877:1-15) Doubt cannot deliver such conclusive satisfaction. “The irritation of doubt” triggers a “struggle to attain belief.” It is this struggle that Peirce terms enquiry. So, summarily, enquiry is the struggle to move from the irritation of doubt to the satisfying state of belief. As mentioned above, the end of enquiry may be true or false but remains the end as long as we have arrived at a settled opinion; for we are not motivated by the truth since the proof that an opinion is true or false lies outside the mind and, therefore, cannot affect the mind. Peirce asserts that this position renders false three conceptions of proof, namely, (i) the argument that enquiry begins with someone posing any question he likes, (ii) the theory that enquiry is about the search for certainty even regarding issues over which no doubt is cast, and (iii) the theory that once everyone is convinced about a matter, enquiry about that matter may continue. (Peirce 1877:1-15) c. Methods of Fixing Belief Peirce concludes “The Fixation of Belief” by examining four methods of fixing belief with a view to determining which of them is the most effective. The first method he considers is the “method of tenacity” (Peirce 1877). Here, he argues that our instinctive distaste for an undecided state of mind makes us default to views we already hold, particularly those we find agreeable. Belief, however, cannot be successfully fixed through such tenacious hold on already-held believes as we can be pressurized by the opinions of others to change our mind. Thus, the method of tenacity is effectual for fixing belief. The second method Peirce examined is the “method of authority. (Peirce 1877). The method of authority, as a means of fixing belief, swings attention from the individual to the beliefs of social institutions. Commonly-held beliefs, in spite of being socially imposed or regulated, have proved to be more lasting than beliefs fixed through the method of tenacity. The downside of this method is that not all beliefs can be socially fixed and people may change their mind when they discover that beliefs communally-held elsewhere are different or better than those of their own communities. The third method of fixing belief is the “a priori method” (Peirce 1877). This is an inductive method that is based largely on sentiment. Though superior to the two earlier methods, the a priori method of fixing belief is subject to change when the taste or sentiment of the individual changes. It is thus very unreliable. Moreover, when individuals change environments and are exposed to intuitions different from their earlier ones, they may doubt their previously-held assumptions and, to resolve that doubt, there might be an abandonment of earlier beliefs in preference for new ones. So, the a priori method is not a satisfactory method of fixing belief. It is relevant to note that the above three methods relied, in different ways, on thinking, and yet proved ineffective for fixing belief. It is, therefore, necessary that a method hinged on “some external permanency,” on “something upon which our thinking has no effect” (Peirce 1877) should be found as a more objective and effective way of fixing belief. For this desirable method to be objective, it must be such that any individual can adopt it and replicate the same result. This is the method Peirce calls “the scientific method” (Peirce 1877). Through experimentation and experience, it effectively erases our doubts by investigating external data that cannot be falsified by human emotion. The scientific method is superior to the other three methods and the impressive successes human beings have recorded over the years via the scientific method affirms its superiority as a method of fixing belief. In addition, the scientific method, unlike the three methods earlier considered, has the capacity to prove itself right or wrong, to detect in its process or outcome bad reasoning or good reasoning. The scientific method of fixing belief, though, is not superior to others in every respect. d. Peirce’s Pragmatic Epistemology The foundations, scope, and validity of Peirce’s pragmatism are laid out in his writings, “The Fixation of Belief” and “How to Make Our Ideas Clear.” Much of the foundational propositions are made in the former while the latter publication amplified and expatiated upon the core issues to crystallize Peirce’s three grades of clarity. Having earlier examined Peirce’s thesis as presented in “The Fixation of Belief,” our focus here shall be on those sections of “How to Make Our Ideas Clear” that we have not yet touched on but which are essential in building the central argument of this study. e. Of Clearness and Obscurity Peirce takes on the issue of clearness, distinctness or obscurity of ideas in the first section of “How to Make Our Ideas Clear.” Of this he says: A clear idea is defined as one which is so apprehended that it will be recognized wherever it is met with, and so that no other will be mistaken for it. If it fails of this clearness, it is said to be obscure… A distinct idea is defined as one which contains nothing which is not clear. (Peirce 1878) To distinctly understand an idea, he says, there is need to define it, for “an idea is distinctly apprehended…when we can give a precise definition of it, in abstract terms” (Peirce 1878). While definitions may teach us nothing new, they enable us to set our ideas and beliefs apart – to clarify them. An unclear idea breeds confusion, when not highly misleading. Clarity of thought, therefore, is a much higher goal than distinctness of thought. Dwelling further on the subject of obscurity, Peirce points out two forms of deceptions obscurity could give rise to. One is the tendency to mistake the sensation arising from our mental clutter for a character of the object we are thinking about, with the possible effect of wrongfully attributing mysterious qualities to the object. Another form of deception is in mistaking a mere difference in the way the same ideas are expressed as a basis for treating them as different ideas. Grammatical vagueness does not amount to inconsistency in the nature or quality of an object. f. Peirce’s Concept of Reality Peirce describes reality as “those characteristics that are independent of what anybody may think them to be” (Peirce 1878). In his view, only experimentation and experience can distinguish and prove such characteristics. But certain experiences cannot be replicated via experiment. Would that make them unreal? Such considerations might have led Peirce to clarify his tentative definition: …we may define the real as that whose characters are independent of what anybody may think them to be. But, however satisfactory such a definition may be found, it would be a great mistake to suppose that it makes the idea of reality perfectly clear. Here, then, let us apply our rules. According to them, reality, like every other quality, consists in the peculiar sensible effects which things partaking of it produce. The only effect which real things have is to cause belief, for all the sensations which they excite emerge into consciousness in the form of beliefs. (Peirce 1878) If belief is the experiential end of reality, are all the things people believe in, therefore, real? Are real things the only things that cause belief? If not, there is need to be more specific in isolating the key element(s) or factor(s) that prequalify a thing as real. Peirce, below, brings in that missing element – the imperative of investigative knowledge – in his, one might say, final definition of reality. As he puts it, The opinion which is fated to be ultimately agreed to by all who investigate is what we mean by the truth, and the object represented in this opinion is the real. That is the way I would explain reality. (Peirce 1878) Of critical importance is the observation that “reality is independent, not necessarily of thought in general, but only of what you or I or any finite number of men may think about it” (Peirce 1878). In other words, what anyone outside the bracket of “all who investigate” thinks about the reality or otherwise of an object amounts to dispensable opinion. Notice should be taken that shallow investigation is not the intendment of Peirce here; rather, he insists on “investigation carried sufficiently far” (Peirce 1878). g. Peirce’s Calibration of Belief In Peirce’s concept of reality, discussed above, we noted that belief is the experiential end of reality. In other words, belief, when based on reality, is synonymous with reality. It is within this context that Peirce’s gradation of belief, stated below, also amounts to his calibration of reality. Peirce: And what, then, is belief? …We have seen that it has just three properties: First, it is something that we are aware of; second, it appeases the irritation of doubt; and, third, it involves the establishment in our nature of a rule of action, or, say for short, a habit. (Peirce 1878) For Peirce, the basis for every real differentiation of thought is its tangible and practical effect (its resultant habit or rule of action). Habit is the end of a trichotomous process in Peirce’s “grades of clearness” of conception of reality that begins with awareness, scales up to definition, before being externalized as action or habit. In a sense, this trichotomy is reflective of some aspects of the cenopythagorean categories of Peirce’s phenomenological paper, “On a New List of Categories,” (Peirce 1867) particularly the triadic features discussed under “As universe of experience,” “As quantity,” and “Technical definition” (Peirce 1867). Peirce’s three grades of clearness of conception of reality are as follows:

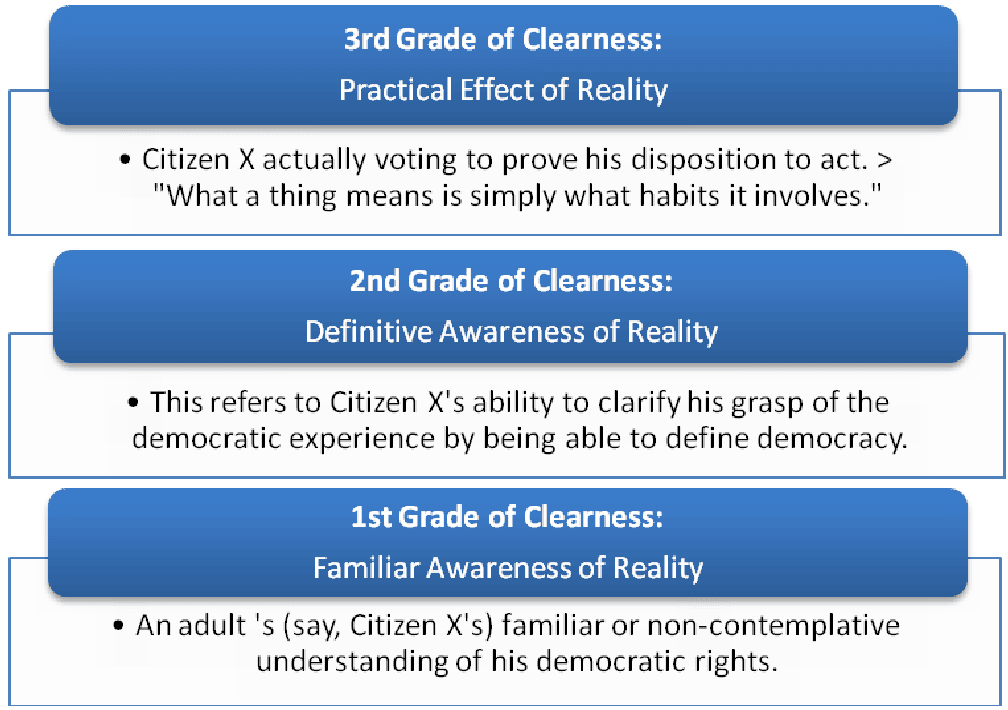

To further simplify this three-tier gradation, we can illustrate the triadic progression as follows:

So, we are firstly made aware of something, secondly we are prompted by doubt to clarify or define it, and thirdly the effect of what we perceive and distinctly know is expressed in the actions we take. 5. Pragmatic Maxim: A Heuristic and Method of Reflection Peirce introduced what he later called the pragmatic maxim in 1878 as “the rule for attaining the third grade of clearness of apprehension” (Peirce 1878). A heuristic approach to problem-solving, the pragmatic maxim is at the centre of the universal popularity of pragmatism. Although Peirce had more than once revised the wording of the maxim, its 1886 original, the version stated in his “How to Make Our Ideas Clear,” and reproduced below, is usually preferred. The pragmatic maxim: Consider what effects, that might conceivably have practical bearings, we conceive the object of our conception to have. Then, our conception of these effects is the whole of our conception of the object. (Peirce 1902) This was the version Peirce himself included in his 1902 definition of “Pragmatic and Pragmatism” in the Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology. The import of the maxim is that the real meaning of any thought or idea rests upon the practical effects of that thought or idea. This makes the pragmatic maxim a useful guide to the apprehension of mental conceptions, a self-applicable system for sifting thoughts of practical relevance from mere verbiage or mental clutter. As an encapsulation of Peirce’s pragmatic doctrine, the maxim is a tool for ensuring that every concept has a matching or corresponding relevance in practice. But the pragmatic maxim is more than a call to action. It is also a method of reflection. It could be argued, and Peirce would seem to agree, that action or habit (as inhered in the maxim) is the doing part of a reflective end. In other words, we progress from perception to doubt, and from doubt to belief. Belief then predisposes us to act. The question is: is our action an end in itself or a means to an end? And if a means to some end, is that end included in or anticipated by the pragmatic maxim? To the author of the pragmatic maxim, Peirce himself, we now return for answers: The study of philosophy consists, therefore, in reflexion, and pragmatism is that method of reflexion which is guided by constantly holding in view its purpose and the purpose of the ideas it analyzes, whether these ends be of the nature and uses of action or of thought… It will be seen that pragmatism is not a Weltanschauung but is a method of reflexion having for its purpose to render ideas clear. (Peirce 1902) What one could decipher from Peirce clarification, made about two decades after the drafting of the maxim, is that “whether these ends be of the nature and uses of action or of thought” they are in the service of a higher end “to render ideas clear”. So, reflective clarity is the ultimate trigger of pragmatic action. Simply put, pragmatic action is embedded in pragmatic thought. John Dewey, one of the classical pragmatists, in an article published in Journal of Philosophy, criticized the application of Peirce’s pragmatism as a tool of enquiry, arguing that Peirce proposed it to be a mere explanatory term. Quoting Peirce’s assertion that “the most striking feature of the new theory was its recognition of an inseparable connection between rational cognition and human purpose” (Peirce 1905:163), Dewey claims: Peirce confined the significance of the term to the determination of the meaning of terms, or better, propositions; the theory was not, of itself, a theory of the test, or the truth, of propositions. Hence the title of his original article: “How to Make Ideas Clear.” (Dewey 1916:710) However, when comparing Peirce’s pragmatism with that of William James, Dewey notes an interesting distinction. He says that while James emphasizes that the “effective meaning of any philosophic proposition can always be brought down to some particular consequence…whether active or passive” (William 1904:673), Peirce “puts more emphasis upon practice (or conduct) and less upon the particular; in fact, he transfers the emphasis to the general.” (Dewey 1916:711) This distinction, by implication, enlarges Dewey’s view of Peircean pragmatism beyond “determination of the meaning of terms.” In reviewing Peirce’s complementary work, “The Fixation of Belief,” Dewey could not but note that “pragmatism identifies meaning with formation of a habit, or way of acting…” (Dewey 1916:711) This statement identifies a given “habit or way of acting” as a test or indicator of the truth of a given proposition. Its applicability as a test or tool of enquiry, therefore, is an integral aspect of the pragmatism of Charles Peirce. List of Works Cited Bain, Alexander, Emotions and the Will, ch. XI, Liberty and Necessity, sect 22,1859, p.595 Dewey, John “The Pragmatism of Peirce.” The Journal of Philosophy, Psychology and Scientific Methods, vol. 13, No. 26, Dec. 21, 1916, p. 710 Engel, Pascal. “Belief as a Disposition to Act: Variations on a Pragmatist Theme”. Online publication accessed on February 2016.https://www.researchgate.net/ publication/253863918_Belief_as_a_Disposition_to_Act_Variations_On_A_Prag matist_Theme Hartshorne, C and Weiss, P eds., The Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce, Vols. 1-6 and A. Burks ed., Vols. 7-8, Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1974. James, William, “The Pragmatic Method,” The Journal of Philosophy, Psychology and Scientific Methods, Vol. 1, No. 25, Dec. 8, 1904, p. 673 Knowledge: Critical Concepts, Vol. 1, edited by Stehr, Nico and Grundmann, Reinar. Routledge, 2005, p. 26 Peirce, C.P 5.12, 1907 Peirce, Charles S., 1902, CP 5.13 note 1. Peirce, Charles S., “How to Make Our Ideas Clear” in Popular Science Monthly, v. 12, (1878), pp. 286–302. Reprinted widely, including Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce (CP) v. 5, paragraphs 388–410. Peirce, Charles S., “On a New List of Categories,” American Academy of Arts and Sciences, May 14, 1867. Peirce, Charles S., “Pragmatic and Pragmatism” Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, 1902. Peirce, Charles S., “The Fixation of Belief,” Popular Science Monthly, Volume XII, November 1877, pp. 1-15. Peirce, Charles S. “What Pragmatism Is” The Monist, Vol. XV. No. 2. April, 1905, p. 163 |

||||

|