Journal of Education, Humanities, Management and Social Sciences (JEHMSS), Vol. 1, No. 3, August-September 2023. https://klamidas.com/jehmss-v1n3-2023-03/ |

||||

|

Vital Force, Personhood, and Community in African Philosophy: An Ontological Study Innocent C. Ngangah

Abstract Vital force is believed to be a peculiar trait of African philosophy and the cosmology which defines and shapes the framework within which the interwoven concepts of personhood and community, as extensions of Africa’s concept of “being”, are founded and reified. Vital force is at the core of Africa’s understanding of life which is deemed to begin from the creator, from whom all created spring. Vital force permeates all creation, including every aspect of the environment from where the person and the community jointly suck sustenance. Identifying this force as the core of the key differences between African and Western philosophies, the study underpins certain fundamental distinctions, namely: Africa’s dynamic notion of being vs. the static concept of Western philosophy; the inclusive view of community in African philosophy vs. the reductionist notion dominant in Western societies; and Africa’s notion of human rights as a derivative of communal rights vs. Western notion of human rights as individualistic rights. Keywords: vital force, personhood, community, African philosophy, Western philosophy, ontology

Ontology, the study of the nature of being, is the most general subdivision of metaphysics (Wallace 2011). Since Parmenides’ claim that being is fixed, changeless and imperishable (DeLong 2019), philosophers have continued to grapple with the intrinsic meaning of reality which, according to Heraclitus, is in a constant state of flux (Graham 2019). Of the many debates provoked by this issue, Plato’s theory of forms (Mason 2010) and Aristotle’s contradictory response to it (McMahon 2007) have remarkably shaped the thinking of many Western philosophers as well as influenced their appreciation, or lack thereof, of African ontological categories. Even African philosophers, who have tried to redefine being within the context of African experience (Kanu 392), beclouded by Aristotelian dogma on the question of substance and accident (Ogbonnaya 108), have failed to share a common perspective on what constitutes Africa’s notion of “being”. Given the foregoing, this paper sets out to posit that in spite of ingenious attempts by many African philosophers to define “being” in the light of their respective ethnic cosmologies, Tempels’ oft-maligned rendition of the Bantu, nay African, concept of “being” as “vital force” (Tempels, 1959), if appropriately interpreted outside the standpoints of colonial discourse, may well serve as a genuine Africa-wide concept of being, albeit one that has diverse linguistic expressions in different African countries. Vital force, taken as the epicenter of Africa’s ontological scheme, is fundamental to a proper understanding of the inter-related and sometimes fused nature of the concepts of personhood and community in traditional African societies. Although the individual and the community act upon each other, the latter exacts a subsumable force on the former in traditional and urbanized African environments. To further strengthen its claim that vital force is a peculiar trait of African philosophy, this paper, towards the end, will feature a comparative analysis of Western and African concepts of “being”, with emphasis on the ontological core of the latter as vital force (Tempels, 1959).

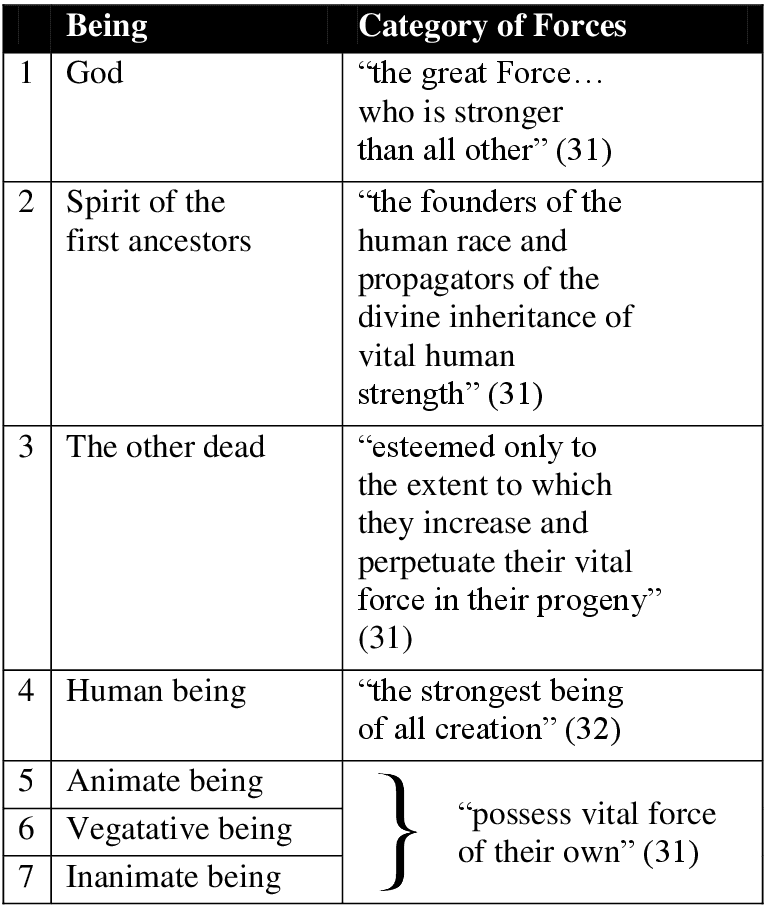

Placide Tempels’ notion of “being” in African philosophy is contained in his epochal work, Bantu Philosophy. The book, first published in Dutch and later translated into French (Rubbens, 1952) and English (1959), is widely regarded as the first major book on African philosophy. It was written by a European missionary who worked among a group of Bantu-speaking Africans during the colonial era. The book, in both content and title, shocked the average Westerner whose prevailing mindset was aptly captured in the preface written by Prof. E. Possoz: Up to the present, ethnographers have denied all abstract thought to tribal peoples. The civilized Christian European was exalted, the savage and pagan primitive man was denigrated. Out of this concept a theory of colonisation was born which now threatens to fail everywhere. (Tempels, 1959) With all its limitations, Tempels’ book, in general, ran contrary to this mindset. His Bantu Philosophy made him the first philosopher to formulate a logically coherent African ontological system. His methodical research, conducted among ordinary Bantu-speaking Luba people, resulted into a dynamic ontological structure which is theoretically different from Western philosophy’s static concept of “being”, challenged racist misgivings about the philosophical acumen of the African, and led to global awareness of African philosophy. Tempels’ book proved that the African’s “philosophical categories can be identified through language, culture and metaphysical attributes of their lives” (Nkulu-N’Sengha, 2017). Tempels made the following basic observations about the philosophy of the Bantu people: The transcendental and universal notions of being and of its force, of action, and of the relationships and reciprocal influences of beings make up Bantu philosophy. This domain is accessible to the ordinary intelligence of every normal “muntu”… The subjective point of view of the Bantu founds the general principle and notion of being on the argument of authority and on their own observation of the constitution of the universe… The general conception of being which one may hold and the knowledge of the particular qualities of each individual being are two distinct things (51). Tempels’ book is in 7 chapters, namely, in chronological order, “In search of a Bantu philosophy”, “Bantu ontology”, “Bantu wisdom or criteriology”, “The theory of the “Muntu” or Bantu psychology”, “Bantu ethics”, “Restitution” and “Bantu philosophy and our mission to civilize”. The last chapter, a repudiation of Western colonial attitudes, began with these sentences: If we are justified in the hope that we have plumbed the depths of the primitive soul in this treatment of Bantu philosophy, we shall be obliged to revise our fundamental ideas on the subject of “non-civilized” peoples: to correct our attitude in respect of them. This “discovery” of Bantu philosophy is so disconcerting a revelation that we are tempted at first sight to believe that we are looking at a mirage. In fact, the universally accepted picture of primitive man, of the savage, of the proto-man living before the full blossoming of intelligence, vanishes beyond hope of recovery before this testimony (Tempels 109). This positive tone, notwithstanding, a number of African philosophers have expressed reservations about some aspects of Tempels’ findings while others have endorsed his main conclusions about Africa’s notion of being. We will review some of the objections raised against Tempels’ work later but let us discuss first his key conclusions about African ontology. African ontology, according to Tempels, is the foundation of African philosophy. The African’s notion of “being” or reality shapes his thought and behaviour, and this notion, asserts Tempels, is “centred in a single value: vital force” (29): Certain words are constantly being used by Africans. They are those which express their supreme values; and they recur like variations upon a leitmoti present in their language, their thought, and in all their acts and deeds. This supreme value is life, force, to live strongly, or vital force. … Force, the potent life, vital energy are the object of prayers and invocations to God, to the spirits and to the dead… In every Bantu language it is easy to recognize the words or phrases denoting a force, which is not used in an exclusively bodily sense, but in the sense of the integrity of our whole being. He says this vital force or “vital energy”, to the African, is the focus of “prayers and invocations to God, to the spirits and to the dead” and that this notion of “being” is not just limited to the Luba linguistic group but that “In every Bantu language it is easy to recognize the words or phrases denoting a force, which is not used in an exclusively bodily sense, but in the sense of the integrity of our whole being” (31). Before we go further, we need to note the significance of the phrase, “In every Bantu language”. Although Tempels’ research was primarily centred on the Luba, he corresponded with missionaries in other Bantu-speaking parts of Africa, and some evidence of such correspondences on the topic of “vital force” are preserved in his footnotes. Perhaps, this was what led to his use of this phrase. “In every Bantu language” indicates a plurality of languages under this vast language group. As Bendor-Samuel (2017) explains: Bantu languages, a group of some 500 languages belonging to the Bantoid subgroup of the Benue-Congo branch of the Niger-Congo language family. The Bantu languages are spoken in a very large area, including most of Africa from southern Cameroon eastward to Kenya and southward to the southernmost tip of the continent. Twelve Bantu languages are spoken by more than five million people, including Rundi, Rwanda, Shona, Xhosa, and Zulu. Swahili, which is spoken by five million people as a mother tongue and some 30 million as a second language, is a Bantu lingua franca important in both commerce and literature. As will be noted later in this paper, Tempels’ fortuitous use of a Bantu language group has both philosophical and linguistic significance. Meanwhile, let us see what nature of beings possess the aforesaid vital force: “In the minds of Bantu, all beings in the universe possess vital force of their own: human, animal, vegetable, or inanimate” (31) and this vital force springs from God – “the Bantu speak of God himself as ‘the Strong One’, he who possesses Force in himself. He is also the source of the Force of every creature.” (31) Tempels’ Bantu (African) hierarchy of beings emanates from his belief that “the key to Bantu thought is the idea of vital force, of which the source is God… The fundamental notion under which being is conceived lies within the category of forces.” (32) This “category of forces” can be represented as follows:

All these beings exact force on each other with God disposing the highest influence of all. Next to God in influence is the human being: “Each being has been endowed by God with certain force, capable of strengthening the vital energy of the strongest being of all creation: man.” (32) So, Tempels’ scheme of forces is essentially anthropocentric: “Vital force is the reality which, though invisible, is supreme in man. Man can renew his vital force by tapping the strength of other creatures.” (32) Tempels then made an interesting comparison between Western and African concept of “being”, describing the former as “static” and the latter as “dynamic”. He said that the West, borrowing from Greek philosophy, defines “being” as “what is” or “anything that exists” and wrongfully presumes that this “static conception of being” is universally applicable. Herein is to be seen the fundamental difference between Western thought and that of the Bantu… We can conceive the transcendental notion of “being” by separating it from its attribute, “Force”, but the Bantu cannot. “Force” in his thought is a necessary element in “being” and the concept “force” is inseparable from the definition of “being”. He described the Bantu as having “a double concept concerning being” and warns that describing Bantu notion of being as “being is that which possesses force” would be inaccurate: “Force is not for them an adventitious, accidental reality. Force is even more than a necessary attribute of beings: Force is the nature of being, force is being, being is force… in contradistinction to our definition of being as “that which is” or “the thing insofar as it is”, the Bantu definition reads, “that which is force”, or “the thing insofar as it is force”, or “an existent force” (34). The foregoing are the key aspects of Bantu notion of “being” as analyzed by Tempels. Some African philosophers have objected to some of Tempels’ conclusions while others have not only done so but have also offered alternative ontological viewpoints they consider more authentically African. 3. African Philosophers’ Counter Notions of “Being” The three main non-theological objections to Tempels’ conclusions regarding Africa’s notion of “being” can be itemized as follows:

We will consider each of these objections as they arise in our highlight of alternative notions of “being” projected by some African philosophers. Below are the views of representative African philosophers who have written about this issue from different parts of Africa. We will begin with Alexis Kagame, whose view of Africa’s notion of “being” is closest to Tempels’. In 1956, Kagame published his PhD thesis, La Philosophie Bantu-Rwandaise de l’Etre. That notable work of ethno-philosophy became his major contribution to African philosophy. His views are not, strictly speaking, a critique of Tempels’ but rather a variation of the latter’s theory. Kagame, based on his study of the Bantu people of Rwanda, categorized African philosophy into four principal forces: Muntu (human being), Kintu (thing), Hantu (place and time), and Kuntu (modality). What this means, in Kagame’s ontological scheme, according to Janheinz Jahn, is that “Everything there is must necessarily belong to one of these four categories and must be conceived of not as substance but as force.” (Negedu, 2014) Common to and qualifying these four forces is not the prefix of each word but, rather, the determinative, “Ntu”. Each of Kagame’s four forces represents more than their bracketed meanings indicate on the surface. For example, “though all human beings are Muntu, not all Muntu (Bantu) are human beings, as Muntu includes the living, the dead and spirits” (Negedu, 2014). However, all muntu possess human intelligence; this makes the other categories mentioned above to be dependent on muntu. As for Kintu, what it represents includes animals, plants and all inanimate objects. All of these are energized by “Ntu”: Hence, in the opinion of Kagame, the underlying category of being is Ntu. Ntu is the ultimate cosmic principle that permeates every nature… Ntu, therefore, is a force that manifests itself in individual beings or things. It does not exist alone. This is why it is seen attached to categories such as Mu, Ki, Ha and Ku. (Ogbonnaya 111) Ogbonnaya rightly regards “Ntu” as “the spiritual dimension of being or reality while the four categories of being are the physical dimensions of being or reality.” (112) However, in reflecting some of the aforesaid objections to Tempels’ ontology (Kagame’s primary inspirational root), he erroneously asserts that: (Ntu) is like the Tempels’ vital force or force. But it goes beyond Tempels’ force as he (Kagame) notes that it is not just a physical force. Kagame gives this force an ontological meaning rather than a physical meaning. This is a widespread but incorrect view. Tempels never created the impression that his force was “just a physical force”. Rather, he said that the Bantu have “a double concept concerning being”, which leads to the understanding that although the Bantu force is physical, embedded in their “force is being, being is force” notion is a potential for philosophical abstraction. That is why Tempels says that “Force is not for them an adventitious, accidental reality. Force is even more than a necessary attribute of beings: Force is the nature of being, force is being, being is force”. In other words, adapting the context of the Aristotelian principle, “being” is “what is” and “force” is equally “what is”; so, for the Bantu, “what is” is ontologically “being” and epistemologically “force”. The dynamic unity of this Bantuan wedlock of substance and accident is often lost to Tempels’ critics who refuse to accept that there are other concepts of being other than Aristotle’s. Although Aristotle posits that substance can exist independent of accident, in Bantu concept of being, as documented by Tempels, substance and accident co-exist as two sides of the same coin. The obvious difficulty we experience here in interpreting the Bantu concept of “being” indicates that nobody can replicate the Bantu concept of existence using Western ontological categories. However, the Bantu notion of “being” as it pertains to human beings (“the strongest being of all creation”) can be better understood via Heidegger’s expression, “Dasein” (1962, 27). This is a German compound word whose components are “da” (there) and “sein” (being). Together they mean “being there”; to exist is being there. But in Bantu cosmology, muntu (Bantu word for human being) cannot be “da” (there) without being inseparably an “existent force”. Therefore, for the Bantu, being there (dasein) is being an existent force. This being-force fusion is particularly appropriate for muntu who, like Heidegger’s being, is a practical being of the world (Collins and Selina 61). Apart from Kagame, other African philosophers who tried to interprete Africa’s notion of “being” ended up, basically, giving us their ethnic group’s translation or extension of the word, “being” (Edeh, 1985 and Iroegbu, 1995) or some ethno-philosophic attribute(s) of “being” (Ramosa, 2002 and Asouzu, 2011). Edeh in his book, Towards an Igbo Metaphysics, essentially conducted a linguistic analysis centred around his “onye” (person) and “ife” (thing) hypothesis that ultimately led to the Igbo word, “ifedi” (“ihedi”) which literally means “what is”, an everyday Igbo expression, not one coined by Edeh. This is rather curious when it is noted that Edeh began his enquiry by claiming that “the Igbo has no word that exactly translates the English word ‘being’” (1985, 93). Apart from translating being as “ifedi”, Edeh failed to tell us what Being (“ifedi”) means in Igbo cosmology. He did say that within that context the “notion of being could be derived from our concept of man” (1985, 100) but never told us what that notion is. Iroegbu (1995), sharing the same cultural roots with Edeh, disagrees with the latter’s approximation of “being” as “ifedi”; he prefers another Igbo word, “uwa”, which literally means “world”. Iroegbu invests the term, uwa, with ontological meaning, pointing out that: The entirety of existence, from God the highest being to inanimate beings of our cosmos can be summarized in the englobing concept of the Igbo term Uwa. Uwa is all-inclusive. It mirrors being, existence, entity, all reality…animate and inanimate, visible and invisible. It is comprehensive, universal…It has transcendent and immanent scope as well as explicative and progressive elasticity. (1994, 144) According to Iroegbu, uwa has 15 connotations but in time-space context it has six zones, five of which are located in spiritual realms and only one of which is earthly. In Iroegbu’s opinion, uwa is “being”, any form of being, and none of his beings are supposedly bifurcated since they are all enclosed in his ontological globe. The fact is that Iroegbu’s book is an interesting piece on the metaphysical connotations of the Igbo word, “uwa”, but he certainly did not succeed in turning that word into an acceptable definition of “being”. The next African philosopher who tried to redefine “being” is the South African philosopher, Mogobe Ramosa. His views reflect his pan-Africanist inclinations. His book, African Philosophy through Ubuntu (2002), positions “ubuntu” as the foundation of African philosophy. In spite of sharing the same stem, “ntu”, with the four words representing Kagame’s four forces of African philosophy, Ramosa’s “ubuntu” concept is clearly different from Kagame’s notion of being as “force”. In Kagame’s, the fundamental category of being is Ntu” (force) while Ramosa’s “ubu” is the essence of being. It should be noted, however, that Ramosa’s “ubu” cannot manifest in concrete form except through “ntu” (the epistemological being). Both are bound together and none can exist independent of the other, just as Kagame’s “ntu” can only manifest as a concrete being only when bound to Mu, Ki, Ha and Ku. This two-in-one reality makes Ramosa to conclude that: ubu-ntu is the fundamental ontological and epistemological category in the African thought of the Bantu–speaking people. It is the indivisible one-ness and wholeness of ontology and epistemology. (2002, 41) One should add that Ramosa’s “ubuntu” concept makes sense only when narrowed to a specific being – the human being (“umuntu”) – for the word, “ubuntu” literally means “humanity”. Since not all beings are human beings, this cannot be an all-inclusive meaning of “being”. Innocent Asouzu’s notion of “being” is an all-embracing one. Using the Igbo aphorism, “ibuanyidanda” (“nothing is too heavy for Danda, the ant”), he conceptualizes an elastic ontology that stretches its scope, in the spirit of cooperation and complementariness, to accommodate all forms of existence within a non-bifurcated, unified whole. As he puts it: If now a philosophy of essence polarises reality, ibuanyidanda philosophy explores a method and principles for coalescing the real and the ideal, the essential and accidental into a system of mutual complementing units. It is a challenge to show how philosophy can be relevant to all units constituting a whole, such that the essential and accidental, the necessary and contingent, the universal and the particular, the absolute and relative…the transcendental and world-immanent, can more easily be between being and its negation. This is why within this context the negation of being is nothingness. (Asouzu 101-102) Asouzu sees every being as an agent performing a role that fills a vacuum in the theatre of reality and, from this standpoint, opines that beings essentially exist to perform functions that close gaps in reality’s interconnected chains: In Ibuanyidanda philosophy, I see it otherwise. Hence, I dare define the idea of being; here I claim that being is that on account of which anything that exists serves a missing link of reality. In other words, within an Ibuanyidanda context reality presents itself to us as missing links of reality within whose framework the idea of being reveals itself and is defined. Asouzu (2007) is known to have criticized Temples’ categorization of beings as forces, and this could be one of the reasons he articulated his own vision of being in African philosophy. In making his own notion of being non-bifurcated, he cleverly guided it away from the strong pull of Aristotle’s substance-accident concept. But “ibuanyidanda” definitely is not being, although it could be said to be an extended attribute of being.

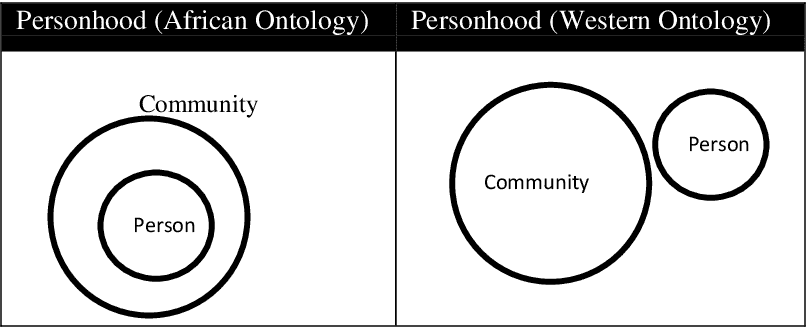

We will explain here how Tempels’ vital force thesis is reflected fundamentally in Africa’s concept of personhood, community, and human rights. Africa’s “dynamic” notion of “being” as vital force determines the nature of its social organization. How expansive is this dynamic concept of being? Tempels expatiates: African peoples…still preserve their essentially dynamic concepts of being, of growth and diminution of being, of the interdependence and interaction of beings, of vital ranks and of the ontological hierarchy. Their ontology remains over attached to their ancient and indestructible faith that all life proceeds from God or from our own conformity with the laws of the natural order of things. (Tempels 115) Below, we will look at how this conformity with natural vital forces is expressed with regard to the way the community is organized, the way the individual is conceived, and the way human rights are understood and administered in the African traditional setting. (a) Vital Force, Community and Personhood in African Philosophy For Tempels, as earlier noted, the key to the African’s thought and behavior is “the idea of vital force” and “the fundamental notion under which being is conceived lies within the category of forces.” Of the seven forces that make up Temples’ hierarchy of forces, of which the first is God, three are essentially human. These three are: spirit of the first ancestors, the other dead, and living human beings. Beneath these three human forces are three non-human forces, namely, animate being, vegetative being, and inanimate being. These three non-human forces “possess vital force of their own” but are under the control of the human forces. The anthropocentrism inherent in this hierarchy of forces is very glaring but there is an underlying framework that ensures that human beings’ governance of the human and non-human forces, under God, is spiritually and socially streamlined. That framework is founded on the communal understanding that all beings are spiritually interrelated forces that exact consequential influence on all individuals within a given spiritual, ethical and social order. According to Encyclopedia.com: Spirits may be divided into human spirits and nature spirits. Each has a life force devoid of physical form. Individuals who have died, usually ancestors in particular lineages, are the human spirits. These spirits play a role in community affairs and ensure a link between each clan and the spirit world. Natural objects, such as rivers, mountains, trees, and the Sun (as well as forces such as wind and rain), represent the nature spirits. Africans integrate this religious worldview into every aspect of life. (2019) Community life in traditional African society is governed via a customary hierarchy of forces. This force-driven order is defined, sustained, administered and enforced by the community through folkloric practices that involve verbal, material and customary artefacts employed to institutionalize the people’s traditional ways of worship and social system. The individual cannot exalt himself above his community’s religious and social practices because of the hierarchy of forces that ensure communal control over the behaviour of persons and groups. So, as Odozor (2019) has observed, Tempels’ hierarchy of forces is more than an abstract spiritual reality: This hierarchy is also evident in human society, where there are chiefs, clan heads, family heads, older siblings, and so on. Second, Africans believe in a moral order given by God, stipulated by the ancestors in the past. Observing this moral order ensures harmony and peace within the community. What instruments are used to maintain this moral hierarchy. As in every other society, laws basically are used, but these are laws, notes Odozor, that derive their power more from tradition than from coded rules: The moral and religious order in the universe is articulated and expressed in a variety of taboos and customs that prohibit specific actions contravening such order. Taboos and customs cover all aspects of human life: words, foods, dress, relations among people, marriage, burial, work, and so forth… This brings us to the question of personhood in African societies. Whereas in the Western world every individual is assumed to be a person by the mere fact of being an individual human being, in Africa personhood is defined within the context of societal expectations and the significant fulfillment of those expectations by the individual. In the West, personhood is attributed to anyone by the mere fact of their being a human being; in Africa, personhood is invested on deserving individuals by the community. John Mbiti (141) has famously framed it this way: “I am because we are, and since we are, therefore I am.” This means that, in Africa, the individual is not defined apart from his or her society. Rather, it is the society that informally invests him or her with personhood upon their performance of certain social-cum-personal obligations (such as rites of passage, marriage, participation in communal functions, etc) and/or demonstration of competence in the acquisition/awareness of critical lore (such as the community’s oral history and customs). Everyone who qualifies to be regarded as a person, in a cultural sense, is seen and known to have done so through their general conduct and quality of interaction with other members of the community. The mere fact of being an adult does not automatically confer personhood on an individual; often one hears the community referring to an adult who does not play any responsible role in the society as “onye a akaro bulu mmadu”. What this means is that “This being (in spite of his or her vital force) is not yet a person”. (Brackets mine) So, the vital force of the individual only elevates him or her to the level of personhood when the` overarching force of the communal authorities deems them to have qualified for such honour. In the traditional African setting, a person is a subset of a community in an ontological and epistemic sense whereas in the West a person, in both senses, is not regarded as a subset of the community. In Western societies, every individual is a person whether they conduct themselves in line with or against the norms of their community. Using set theory, we can represent African and Western notions of personhood as follows:

In Africa, personhood is conferred on the individual by the community based on his attainment of a prescribed level of social force, and not based on “some isolated static quality of rationality, will, or memory” (Menkiti 1984). We conclude this segment of our discussion with Menkiti’s reference to the incisive distinctions made by Tempels’ Luba people: This is perhaps the burden of the distinction which Placide Tempels’ native informants saw fit to emphasize to him–i.e. the distinction between a muntu mutupu (a man of middling importance) and muntu mukulumpe (a powerful man, a man with a great deal of force)…the word “muntu” includes an idea of excellence, of plenitude of force at maturation…Thus, it is not enough to have before us the biological organism…We must also conceive of this organism as going through a long process of social and ritual transformation until it attains the full complement of excellencies seen as truly definitive of man. And during this long process of attainment, the community plays a vital role as catalyst and as prescriber. (Menkiti 1984) (b) Vital Force and the Concept of Human Rights in African Philosophy The superiority of communal force over the individual’s force, as epitomized by the power of the community to act as the prescriber of personhood criteria, also places the community over the individual in matters of human rights. In the traditional African setting, the rights of the community incorporate, and sometimes supersede, that of the individual. The individual’s rights are governed within the context of communal rights, duties and obligations, as enshrined in the community’s customs and traditions, and in recent communal decisions. In African traditional environment, rights are conceived to preserve and sustain communal living, thereby ensuring that the wellbeing of the majority of communal dwellers is protected against the excesses of any individual. Laws are aimed at preserving the common good over and above the unbridled ambition, exploits and deviant lifestyle of the individual. As a guiding principle, communalism is elevated over individualism. This is in sharp contrast with what obtains in the West where the rights of the individual are deemed as the fundamental natural rights, with negative implications for the quest to build a more egalitarian social order: Human rights ideas in international for a have historically been derived from a Western natural rights perspective. The perspective indeed denies the existence of the needy’s right to economic sustenance and society’s obligation to satisfy this right. The African sense of community obligation that goes beyond charity is just what is needed to foster economic rights and push the idea of economic rights beyond the demands of human rights activists and human rights textbooks. We need to take such non-Western conceptions seriously. Western social scientists are increasingly questioning the sanctity of the liberal individualist paradigm in their search for answers to contemporary Western problems. (Cobbah 311) It should be noted that the supremacy of the communal rights over the individual’s rights does not necessarily approximate to oppression or suppression of any individual. Fair play, fair hearing and due process are integral aspects of the traditional rule of law. The Ghanaian scholar, Asante, who conducted a research on this topic, refreshes our memory in Bennet (1993): The notion of due process of law permeated indigenous law; deprivation of personal liberty or property was rare; security of the person was assured, and customary legal process was characterized not by unpredictable and harsh encroachments upon the individual by the sovereign, but by meticulous, if cumbersome, procedures for decision-making. The African conception of human rights was an essential aspect of African humanism sustained by religious doctrine and the principle of accountability to the ancestral shades (73-4).

We have shown, as observed by Tempels, that African ontology is the foundation of African philosophy and that the concept of vital force, governs personal and social lifestyles and organization in traditional African societies. While a number of African philosophers have propounded their own versions of the African concept of being, none of them has come up with a notion of being definite, authentic and widespread enough to uproot the belief that vital force encapsulates Africa’s notion of being. Indeed, vital force is what sets African ontology apart from Western notion of existence. We have also tried to demonstrate this through our comparative analyses of African and Western notions of personhood, community and human rights. In the light of all this, “We might say that in African conception the capacity for doing is identified with being and therefore with act or perfection…” (Rush in Ogbonnaya 2014). To sum up, we have argued, and hopefully also demonstrated, that in Africa a being is essentially what it is, and what it is also amounts to what it can do. Works Cited Aristotle, The Metaphysics. Translated by McMahon, John H. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 2007 Asante, S.K.B. “Nation Building and Human Rights in Emergent African Nations”. Cornell Int Law Jnl. vol. 2, 1969. Asouzu, Innocent I. “Ibuanyidanda” and the Philosophy of Essence 1. Filosofia Theoretica, vol. 1, no. 1, December 2011 Bendor-Samuel, John T. “Bantu Language”. Encyclopaedia Britannica, January 25, 2017. https://www.britannica.com/art/Bantu-languages. Accessed on September 23, 2019. Bennet, T. W. “Human Rights and the African Cultural Tradition”. African e-Journals Project. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.1027.7005&rep= rep1&type=pdf. Accessed October 6, 2019 Cobbah, Josiah A. M. “African Values and the Human Rights Debate: An African Perspective”. Human Rights Quarterly, vol. 9, no. 3, August 1987, pp. 309-331. DOI: 10.2307/761878 DeLong, Jeremy C. “Parmenides of Elea (Late 6th cn.—Mid 5th cn. B.C.E.)”. The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ISSN 2161-0002s, https://www.iep.utm.edu/, September 20, 2019. Edeh, E. Towards an Igbo Metaphysics. USA: Loyola University Press, 1985. Graham, Daniel W. “Heraclitus”. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Edited by Edward N. Zalta, September 3, 2019. URL https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/ fall2019/entries/heraclitus/>.= https://science.jrank.org/pages/10652/African-Philosophies-Major-Themes.html Iroegbu, I. “Being as Belongingness: A Substantive Redefinition of Being”, Ekpoma Review, 2004 Janheinz Jahn, Muntu: An Outline of the New African Philosophy, (New York: Grove Press Inc; 1961), p. 100. Kanu, Ikechukwu Anthony. “The Quest for the Nature of Being in African Philosophy”, Filosofia Theoretica: Journal of African Philosophy, Culture and Religion, vol. 2, No. 2, 1 July 2013, pp. 391-407(17). Mason, Andrew S. Plato (Volume 8 of Ancient Philosophies). Acumen, 2010. Mbiti, John. African Religions and Philosophies (New York: Doubleday and Company, 1970), p. 141. Menkiti, Ifeanyi A. “Person and Community in African Traditional Thought”. African Philosophy: An Introduction, edited by R. Wright, University Press of America, 1984. Nalwamba, Kuzipa and Buitendag, Johan. “Vital Force as a Triangulated Concept of Nature and s(S)pirit”. HTS Teologiese Studies /Theological Studies, vol. 73, no 3., 2017. htps:// doi.org/10.4102/hts.v73i3.4506 Negedu, Isaiah Aduojo. “Beyond the Four Categories of African Philosophy”. International Journal of African Society Cultures and Traditions, vol.2, no.3, December 2014, pp.10-19. Nkulu-N’Sengha, Mutombo. “Bantu Philosophy”. Encyclopædia Britannica, June 23, 2017. www.britannica.com/topic/Bantu-philosophy Odozor, Paulinus I. “The Essence of African Traditional Religion”. Church Life Journal. University of Notre Dame, 2019. Ogbonnaya, Lucky U, “The Question of ‘Being’ in African Philosophy”, Filosofia Theoretica: Journal of African Philosophy, Culture and Religions, Vol. 3 No. 1 January – June, 2014, p. 108. Rubbens, A. La Philosophie Bantoue. Congo: Lovania, 1952. Tempels, Placide. Bantu Philosophy. Translated by Rubbens, A. Paris: Presence Africaine, 1959. Wallace, William A. The Elements of Philosophy: A Compendium for Philosophers and Theologians, Eugene OR: Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2011.

|

||||