Journal of Education, Humanities, Management and Social Sciences (JEHMSS), Vol. 1, No. 1, April-May 2023. https://klamidas.com/jehmss-v1n1-2023-02/ |

|||||||||||||

|

Human Rights, Democracy, Development and Cultural Pluralism* Duve Nakolisa Abstract Since the end of the Cold War, the world has not known as much instability as it is currently facing. The Russian invasion of Ukraine and the conflagrations arising therefrom have brought the world to the brink of a 3rd World War and to the possibilty of a nuclear showdown. The effects are multifarious, ranging from widespread military outbursts to economic, social and political upheavals. While the Russian-Ukraine war seems to be the immediate trigger of the worsening volatility, there are a number of remote causes, not the least of which are unsettled post-Cold War issues bordering on human rights, democracy, development and the quest for a multi-polar world order. This paper asserts, via critical examination of the relevant matters, that politicization of issues of human rights, democracy, development and cultural autonomy has for long posed a threat to global understanding and would continue to do so unless an attitude of mutual respect and impartiality is adopted towards these issues. It asserts that unbiased and principled approach to such matters would enhance their inherent capacity to serve as veritable basis for peaceful co-existence among nations. Keywords: human rights, democracy, development, cultural diversity Introduction Across the world, no issue attracts emotional response more than the issue of human rights. Other issues, such as democracy, development, and culture gain credence as far as they are seen to enhance the enthronement or defence of human rights. According to Alston (1988): It is now widely accepted that the characterization of a specific goal as a human right elevates it above the rank and file of competing societal goals, gives it a degree of immunity from challenge and generally endows it with an aura of timelessness, absoluteness and universal validity. In the West, nothing is perceived as threatening “the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government” (Fukuyama, 1988) as deeply as the denial or abuse of fundamental human rights. Whatever guarantees the individual’s rights is presumed to guarantee Western democracy since the latter, in principle, is founded on universal suffrage. Whatever threatens individual rights, even when in favour of social stability and communal harmony – in favour of the overriding good of the public – stands censored by the West. The neo-conservative scholar, Michael Novak (1987), offers an explanation: The capitalist conceives of the common good as being rooted not in intentions but rather in the freedom of persons to have their own individual visions of the common good. And these visions, taken together, produce a higher level of the common good that was previously possible. In Montesquieu’s view, individual rights were of fundamental importance because their exercise enabled commerce to flourish. His Doux-commerce postulation was captured in this well-known sentence: “It is almost a general rule that wherever manners are gentle (moeurs douces) there is commerce; and wherever there is commerce, manners are gentle.” (Hirschman, 1987) Having linked human rights with profit, the West appears reluctant to accept any model of democracy other than Western liberal democracy. It does not matter how unsuitable that model might be for a given culture or people. Western human rights aristocrats believe that only Western liberal democracy can guarantee the presumed superiority of “individual” rights over “collective” rights. The question is: Is one really superior to the other? To assist us in determining that, we must first answer the question: Whose heritage are human rights? Human Rigts: Western or Universal Heritage? Let the kite perch, let the eagle perch. He who says another should not perch, let him be hunchbacked. – A Nigerian traditional adage Is the concept of human rights indeed a Western heritage? The Reagan administration once traced the idea of human rights not simply to the West but specifically to the United States. A State Department country report (1982 issue) tracked “the human rights movement in world politics” to 1776 America: It is this historical movement that democratic countries owe their possessions of rights, and because of it that other peoples express their yearnings for justice as a demand for rights. The heritage question is very important because how a country conceptualizes human rights can be a function of how much of their relevance it is able to locate in its traditional ethos. Each country’s faith in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights may sometimes conflict with its faith in its own peculiar human rights heritage. President Reagan, for example, showed more faith in the American Declaration of Independence than in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights when his administration rejected the concept of collective human rights. The philosophical underpinnings of the American Declaration embodied the concept of natural rights as primarily the rights of individuals. The notion of collective rights as human rights – as opposed to the rights of states and organizations – was therefore unacceptable to the Reagan administration. We shall return to this debate later. For now, we need to examine the claims of the Reagan administration that “democratic countries owe their possession of rights” to the United States and that “other peoples express their yearnings for justice as a demand for rights” because of an 18th century American movement. That the American Declaration of Independence influenced the global quest for freedom is not in doubt. But the State Department’s claim denied other vital contributors due credit. A United States NGO, Americas Watch, has effectively attacked this official attempt at rewriting history: Nazism and its effects do not appear in this account, nor is there a single mention of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the worldwide concern that led to its drafting, or the contributions to human rights law and history made by any other nation. Nor is there any suggestion that international law of human rights owes much to powerful anti-colonial movements in the pre- and post-World War II period emanating from what are now called Third World countries. There is a point at which chauvinism becomes misinformation, and this putative history presents the cause of human rights as American property, as un-codified, and therefore malleable and above all as non-neutral, aligned, thoroughly political. Besides the salient points made by Americas Watch, let us note that if human rights were drawn from the “Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God” (in the words of the Declaration of Independence) – and nature is a global reality – it then means that each nation must have imbibed certain human rights concepts from our common nature. If nature can speak to one, it can speak to all. Nature might have spoken to some group of Nigerians in the words of the saying quoted at the beginning of this section. “Let the kite perch, let the eagle perch” probably dates back to a time preceding 1776 as it is a saying generally considered to be almost as old as the ethnic group itself. For the Igbo, it is the oral encapsulation of human right codes and the basic guide for interpersonal relationships. “He who says another should not perch let him be hunchbacked” recognizes the need for sanctions as a deterrent against human rights violations while implicitly condemning partiality in the application of sanctions. Other groups of Nigerians have their own equivalence for “Let the kite perch, let the eagle perch.” And in the rest of Africa, one will find similar pointers to human rights awareness in pre-historic times. The indigenous traditions of Asia, an aspect of which is examined in the next section, have always embodied a credible concept of human rights. Human rights, therefore, are neither native to America nor to any other part of the West. Defending the cause of human rights as if they are, for instance, American property can make such a defender behave like an overbearing landlord rather than a co-tenant in the universal house of common rights. Of Democracy, Human Rights and Cultural Differences Back to Francis Fukuyama who considered Western democracy “the final form of human government” (Fukuyama 1988). There is a fundamental problem in this viewpoint. Unless Western democracy, as we know it, is dead, it can and must evolve into something better. The dynamics of the system will ultimately change it from within or force it to extract change from without. Yes, there is a without. There are other models of democracy. If the ideologues of the Western model insist that this model is democracy’s final logical form, they will be subjecting Western democracy to the same unbalanced diet which malnourished and finally exterminated Soviet communism. Western civilization cannot abandon eclecticism without risking its own death. And if it must be fed by forces outside itself, then it must tolerate the existence of civilizations other than itself. It must be ready to acknowledge that the sun can be viewed from other sides of the planet. This point is very valid because unless other models of democracy are deemed not only respectable but durable, attitudes towards human rights will continue to be mixed up with the optional question of Western democracy. Many human rights groups have already muddled up the two, and while both may be inseparable in Europe and America, they don’t have to be necessarily so in Africa, Asia and Latin America. Packaging human rights and Western democracy into one campaign may make the exercise unpopular in some non-Western countries, thereby tempting the West to use force of whatever nature to enthrone its own model. This will amount to arrogance and intolerance. It is like saying there may be other models of this thing called democracy, other viewpoints, but (in the words of Fukuyama, earlier quoted), “it matters very little what strange thoughts occur to people in Albania or Burkina Faso, for we are interested in…the common ideological heritage of mankind.” The world has become smaller and smaller, yet it has not produced a global dialect. Clans of ideological persuasions still persist. It does not have to be communism or capitalism. Even within capitalism interpretations differ. The world might have become a global village but it can still do without a village head. No single nation, no matter how powerful or influential its military or propaganda arsenals, should usurp that role. Talks about “the common ideological heritage of mankind” make uncommon, therefore destroyable, other heritages. Human rights should not be made inseparable from Western democracy and individualism. Currently, it is more universally acceptable to deal with human rights outside the West as a separate issue. Why is it difficult for the West to do so? I think it is chiefly because of the following Western assumptions:

A former US ambassador to Nigeria once wrote: I think everyone here will recognize a correlation between economic prosperity and enduring democratic governments. By and large, those nations that have the longest continuing democratic governments are also among the world’s most affluent countries. (Carrington, 1995) The basic question is: are assumptions (1) and (2) above necessarily true? To dismiss (1), one simply has to look at the United States. It is the leading economically developed country but has the worst record in the West for violent crimes and murders. We can use this index of illegal termination of life because it is the worst form of human rights abuse. Russia, still groping in the backyard of capitalism for a way out of its communist hangover, may not be marked off by the core West as having achieved EU-standard economic development. Yet, “the murder rate in Mosow in 1993 was around a third of that of New York” (Gray, 1994). Statistics available from sources within America also indicate a reversal of assumption (1): with economic development, crime has increased to erode the human rights of Americans. The paradox is that America has the largest number of human rights groups in the world. Like the United States itself, some of these groups are specially dedicated to monitoring the rest of the world. Assumption (2) is made ridiculous by the industrial miracles of Asian countries such as Japan, Indonesia and Singapore where, as Gray (1994) noted: The model of economic and political development draws on indigenous traditions such as Confusianism and candidly rejects Western ideals of individualism, human rights and democracy. Its track record in delivering prosperity and social stability is so outstanding that we would expect their achievement to be an object of sympathetic interest in the West. The Asian model, in spite of that region’s stock market meltdown in late 1997 and the currency crises which continued to beset it into 1998, remains a proof that although democracy may be about freedom, freedom is not necessarily about Western democracy. In the United States, “more than 1.25 million Americans (are) subject to some form of imprisonment.” To frame the question in Gray’s own words, If the US has been unable to protect the ordinary liberties of its citizenry even with a Draconian policy of mass incarceration, by what right does it judge the Asian countries, among which Japan and Singapore stand out in their success in assuring security from crime for ordinary people? The dynamics of each society should be allowed to dictate for it what mattered most: security and communal harmony (via collective rights) or insecurity and individualism (via over-emphasis on individual rights). Has the West ever paused to consider why in Africa one-party democracies had engineered stability more than multi-party ones? The philosophical currents of indigenous African political systems are more centripetal than centrifugal. From what this writer knows of the West, the opposite appears to be the case there. The political philosophy of many traditional African societies is defined by the seemingly contradictory binary pairs: disagreement/consensus, division/unity, and submission/rotation. In other words, in spite of disagreement and division, a modern African polity reflective of this traditional model would most likely stand as long as it goes by consensus; and to consensual leaders the people would be loyal as long as leadership opportunities are made rotational among the constituent groups. The zero-sum nature of Western democracy is alien to this traditional model of governance and this probably explains why Western democratic practices in Africa are generally so acrimonious, violent and unstable. Conflagrations between ethnic groups are better not promoted in Africa in the name of anything because once disagreements over-stretch the cultural pool of consensus, armageddon is unleashed. Any wonder Liberia or Somalia proved more disastrous than Bosnia. This writer does not believe in romanticizing Africa’s past. Of course, there were ethnic wars but they generally came after extensive peace moves. Conversely, the cultural underpinnings of the West are characterized by a conflict/conquest ethos: conquer to rule; rule to dominate. This cultural lust for conquest often breeds artificial conflicts. It was the ethological inspiration behind colonialism. This principle propelled Hitler who provoked wars just for the fun of winning them. It made Fukuyama talk about the end of history out of the unnecessary anxiety that the end of the great conflict (the Cold War) might result in the absence of another winnable conflict of that magnitude. Life itself and political systems are energized by conflict. But conflict for conflict’s sake appears to be a subconscious attribute of the West and, by extension, of Western democracy. Western individualism waters this lust for conflict. In the West, human rights, in themselves desirable, now provide easy excuses for conflict multiplication. Agitations for new human rights have proliferated in the West, especially in the United States where every conceivable deviant publicly demands for rights. In Africa and Asia, the situation is different. Here, individual rights have traditionally sucked nourishment from the collective. The individual owes his self-expression to the harmony of the community. The common good is a guarantee for the individual good and, where necessary, may supersede the latter. Japan can be used to illustrate this point. There, the driving principle is group loyalty and accommodation. According to a Time (1983) investigation, “although the Japanese have a highly developed sense of individual rights, social harmony, not personal justice, is the basis of their law…” Equality to the Japanese is tempered by deference, by the Confusian “system of social ethics based on five relationships: father and son, older brother and younger brother, ruler and subjects, friend and friend, husband and wife…the Japanese find it easier to deal with one another as unequals than as equals” (Time, 1983). According to Time, the Japanese emphasize the stability of these relationships over individual claims to human rights: The American civic principle is freedom and equality. The Japanese civil logic is mutual obligation, hierarchy and the overriding primacy of the group. Japan is governed by on, by an almost infinitely complicated network of responsibility and debt and reciprocity: what each Japanese owes every other, and what each owes the entire group… Many a Japanese company, reflecting this bond, can truly be called, in the words of Sony’s Aiko Morita, a “fate-sharing vessel”. This is true not only because of widespread factory-worker ownership of a substantial percentage of the shares but because of, in comparison with the United States, the insignificant level of litigation brought against the company by the workers. The American emphasis on individual freedom and equality often invites confrontation and disharmony to ensure the enthronement of these rights. The Japanese enthrone both individual and collective rights by doing exactly the opposite: avoiding confrontation and social discord. This is a case of the same human rights crossing cultural boundaries leading to marked differences in interpretation and application. A typical Western-style human rights campaigner (or his Third World colleague), without appreciable sensitivity to the cultural peculiarities of a given society, will attempt, with the cultural needle of the West, to inject into that society the universal commonwealth of rights. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights and all the international covenants leave room for accommodation of cultural differences. The bottom line is the dignity of the human person or group as enshrined in the provisions: each nation must mould its own cultural shape or perspective with the settled clay of the codes. But no nation or group should impose, by whatever guise, their own preferred shapes on others. Many African and Asian countries are, very often, victims of selective criticism by the West for their human rights records. Human rights questions are used to camouflage political and economic self-interests. One thing that must be said here is that when the Universal Declaration was adopted by the United Nations these countries were not independent. The dominance of Western countries at the time ensured that its provisions were largely individualistic. One notices this tendency most in the West-styled “first generation” rights (Civil and Political Rights) and the “second generation” rights (Economic and Social Rights). Individualism is generally minimal in the “third generation” or so-called new human rights (Collective Rights). It is more than mere coincidence that the “generational” ladder became more collective as African, Asian and Latin American countries, now independent, lent their emphasis on the collective to the debate. Some of the collective or solidarity rights which now enjoy some force of law include the “Right of Peoples to Peace” adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 1984, and the “Right to Development,” adopted by the General Assembly in 1986. The African Charter of Human and Peoples’ Rights (1983) specifically recognizes the right to development, and we will shed more light on this later. The right to humanitarian assistance and environmental rights have also won broad sympathies. The collective rights movement, at present improperly coordinated, will ultimately drive the world to a fresh consensus on human rights in general. Many Western intellectuals are opposed to the adoption of these rights as human rights because they know such a move may query more formally the role the West has played and is playing to perpetuate the underdevelopment of the Third World. If “the Right of Peoples to Peace” and “the Right to Development” are treated strictly as human rights, then the Structural Adjustment Programme of the IMF and the Word Bank in Third World countries will automatically amount to gross violations. These two agencies have masterminded the implementation of economic downsizings which have led to massive enslavement (devaluation in official parlance) of currencies, collapse of local industries, massive unemployment, erosion of living standards, social disruptions and political instabilities. It is high time the world embraced cultural pluralism, a phenomenon behind what Huntington (2011) called “intercivilization” conflicts. In his seminal work, The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order, Huntington argued that cultural distinctions over issues such as democracy and human rights would dominate politics in the post-Cold War world. Within the scope of this discourse, we have looked at cultural differences as they touched on democracy and human rights. But there are other debates we have left untouched. For instance, where human rights conflict with religious injunctions, will it amount to a violation if the latter is given the upper hand? In circumstances of endemic and recurrent military interventions, as used to be the case in Nigeria, where civilians themselves have at times openly invited the military and where calls for what might be called militocivilian democracy have been made by some members of the political class, will it amount to human rights violation if such a unique system gains popular acceptance and workability? Space constraint hinders us from exploring these questions here, but Walter B. Wriston (1987), former President of Citicorp, once spoke a word fit for a preliminary response: “When all is said and done,” he said, “the maximizing of human liberty is the most important moral imperative.” The International Bill versus the New Rights The International Bill of Human Rights is composed of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the international human rights covenants. The covenants include International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), and the two optional protocols to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. The Universal Declaration, which has become an essential guide to the interpretation of the UN Charter, is mainly concerned with human rights emanating from “the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights” of the individual, which rights it declares as “the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world.” The international covenants mainly focus on the duties of States towards the undertaking parties, and assurance by the States to each other that they will respect “all peoples” exercise of the rights contained in the Covenants. The new rights, so-called, which are also known as group or people’s rights, cover such rights as the Right to Self Determination, Right to Development, Right to a Safe Environment, Right to Democracy and the Rights of Minorities. These rights, in reality, are not new as some provisions of the Universal Declaration had already mentioned them, albeit without elaboration, or recognized the principles from which they derive validity. Many Western human rights philosophers, however, have consistently refused to acknowledge them as human rights in the context of international law. When they shift from insisting that they constitute mere principles, they grudgingly concede that while they may serve as rights, they should be cordoned off as group or people’s rights – as distinct from human rights. This is not mere sophistry: the aim is to elevate the “personal” rights of the Universal Declaration over and above the collective claims of the new rights. The new rights appear to subvert the philosophical roots of the Universal Declaration which largely could be traced back to 18th Century Western concept of natural or moral law (Lex Aeterna). The natural rights model considers the Universal Declaration as “clearly and unambiguously conceptualized as being inherent to humans and not as the product of social cooperation. These rights are conceptualized as being universal and held equally by all; that is, as natural rights” (Donnelly, 1982). This argument, a foretaste of which we saw earlier in this discourse, implies that the individual draws his rights from nature, that is, from the mere fact of being a human being; while the group or “people’s” rights derive validity not primarily from nature but from the decisions of individuals within the polity – that is, from social mediation. This reasoning is persuasive but misleading: never at any time has Nature or the inaudible winds of morality attributed any set of rights to human beings. Rather, human beings themselves conceptualized, derived and coded the rights of the Universal Declaration. And since self-preservation is the first law of nature, it is not surprising that most of the provisions of the Universal Declaration seek to ensure personal freedoms. But this should not be reduced to the absurd conclusion that any right which deals with groups of individuals or social concerns is not a human right. The word, “human,” is not controversial; neither should the rights, whatever rights, which it defines or qualifies. All rights derived by humans for the freedom and security of humans in their relationship with humans, nature or human institutions are human rights. Being thus definitively and equally human, all of these rights, for practical purposes, can be sub-divided. They can, as human rights (as defined above) and according to the content of their provisions, be sub-divided into subsidiary categories such as, among others,

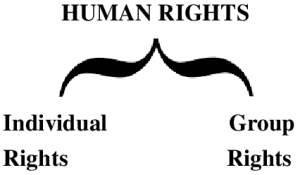

All of these sub-divisions, for ease of reference, can be consolidated into two broad categories:

Outside these two sets, we have the non-human rights, such as the rights of animals or animal rights. When consensus is reached on it, animal rights may be defined as rights derived by humans for the freedom and security of non-human animals in their relationship with humans, nature and human institutions. Hence, this writer posits that human rights, as distinct from non-human rights, constitute or should constitute one body of rights in international law context. Admittedly, making actionable the right to development, peace or self-determination poses extraordinary jurisprudential challenges. How do you define and enforce some of their terms, such as the frequent recourse to “people” rather than “person” or “everyone”? We know who a person is; the question as to who constitutes “people” in the light of a given provision entails sorting out potentially controversial issues of identification and differentiation. These are real problems but we need not run from the desirability of codifying these rights as intrinsic parts of international human rights law or from the harder task of making them justiciable. Elevating the personal or so-called natural rights over the collective or “people’s” rights on the grounds that the personal rights are “above and prior to the state and would continue to exist regardless of action by the international community to revoke their recognition” (Alston, 1988) is overlooking the operative clause of Article 29(1) of the Universal Declaration. This provision states that everyone owes duties to the Community “in which alone the free and full development of his personality is possible.” (Italics mine) The implication: everyone, for all their individual rights, is in a crucible called the Community or the State in which alone he can experience the exercise of his rights. The Community or State is the crucible, the arena of play. The question of human rights arises basically because people are in interaction with people in society. Human rights are about how homo sapiens (thinking human beings) can relate with one another in society. This is why only humans and human institutions – not domestic or wild animals, and not trees – are required to respect human rights. But human rights are not simply about people, not simply about the Community or the State. Human rights are about people in society. Societal interaction generated the need for recognition and observance of these rights. So, there is a social mediation to every human right. Therefore, freedom to exercise individual rights within the framework of social justice should be the directive principle. On the Right to Development The UN Declaration on the Right to Development, like other so-called “Collective Rights”, is often wrongfully given subsidiary importance by governments and human rights activists of the developed countries. Western scholars hail the UN Declaration on Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights as “the basic human rights instruments” (Steiner, 1997). Western human rights defenders sometimes behave as if this is true. Classifying the development of human rights into generations, an acceptable practice in the West, leads to the erroneous order which ranks rights as follows:

The first two generations involve rights enshrined in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) respectively. The so-called Collective Rights, so named to deprive them the personal force accorded the first and second generation rights, include the right to development, the right to safe environment, the right to self-determination, and the right of minorities, among others. Neither the Universal Declaration nor the Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action support this view of compartmentalizing rights into hierarchies or generational classes. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights simply called itself “a common standard of achievement for all peoples and all nations” (UDHR, 1948) while the Vienna Declaration clearly emphasized that “All human rights are universal, indivisible and inter-dependent and inter-related. The international community must treat human rights globally in a fair and equal manner, on the same footing, and with the same emphasis” (VDPA, 1993). Chapter IX of the UN Charter, titled “International Economic and Social Co-operation”, supports the pursuit of “higher standards of living, full employment, and conditions of economic and social progress and development; solutions of international economic, social, health and related problems; and international cultural and educational co-operation.” In Article 22-27, the Universal Declaration on Human Rights clarifies the agenda of the Charter by naming a specific list of economic, social and cultural rights. These rights are expanded in scope and force in the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. The covenant obligates state-parties to enforce these rights. Both the ICCPR and ICESCR were adopted at the same time in 1966 and indeed could as well have been one document if not “because of the different nature of the implementing measures which would generally be involved, and not so as to imply any divisibility or hierarchy among the rights concerned” (Diller, 2012). If the society or community “in which alone”, according to the Universal Declaration , human beings realize their rights is accorded the right to develop, such a right cannot be any less human than the aggregate rights of the persons in the community. The right to development is driven by the need of human beings in any given society to realize their right to personal freedom and pursuit of happiness. Underdevelopment dehumanizes as much as sustainable development humanizes. The right to development, therefore, is the right of humans to realize their full human potentials. Just as, analogically speaking, the right pertaining to the protection of the womb (in which alone the unborn person can exercise other rights) can be said to encapsulate the right of the unborn person, the right to development, in sustaining the flourishing of human rights, can be said to be a human right. Some Western governments tend to de-emphasize this linkage because intrinsically the right to development challenges certain Western practices and approaches that undermine the economic and social aspirations of the developing countries. In 1997, during the 53rd Session of the UN Commission on Human Rights, Western countries demonstrated this attitude in voting against the drafts which later became resolutions 1997/7, 1997/10 and 1997/103. The first resolution, on human rights and unilateral coercive measures, called on all states to desist from implementing economic measures of “a coercive nature with extraterritorial effects, which create obstacles to trade relations among states, thus impeding…the right of individuals and peoples to development.” Developing countries, according to the resolution, are particularly victims of such measures because of the “negative effects (of the measures) on the realization of all human rights of the vast sectors of their populations, inter alia, children, women and the elderly.” Resolution 1997/10 on effects on the full enjoyment of human rights on the economic adjustment policies arising from foreign debt and, in particular, on the implementation of the Declaration on the Right to Development was also critical of the negligent attitude of the developed nations. The resolution called for the establishment of a just and equitable international economic order which will guarantee developing countries the following:

These constitute bona fide rights of developing countries under the principles enunciated in the UN Declaration on the Right to Development. But Western countries, preferring to parrot other rights which do not question the global lopsidedness in development, ganged up to vote against not only the resolution but the related one (1997/103) on the effects of structural adjustment policies on the full enjoyment of human rights. Structural adjustment policies failed woefully in many developing countries because they were addressing cosmetic economic issues rather than the fundamentals. Globalization is a buzzword in today’s economy. It spells profit for Western multi-national companies wading into so-called emerging markets. But unless it also spells responsibility for Western governments, the global stock market crash of 1987 and similar economic catastrophes may continue to occur from time to time. That crash that saw the Dow plunging 22% on October 22, 1987 should have opened the eyes of Western nations to the need for mutually beneficial economic co-operation among nations, including developing nations. The mini crash of 1997, ten years later, emphatically illustrated this point. The latter crash started with currency devaluations in Thailand – and from there it spread to the rest of Asia, including Hong Kong, and then extended its impact to London and New York. The West, fearing that the economic crisis will hurt their investments in South Korea, quickly favoured that country with a $60 billion World Bank loan. Although there were other factors responsible for that crisis, one might opine that if the West had responded to early signs of distress in the economies of the Asian tigers, that economic crisis could have been averted or its impact significantly reduced. An evidence of the bad policies of the West towards the development of the developing countries is the US’ exit from the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) in 1996. Its exit diminished the impact of that organization in developing countries. It also gave a wrong signal leading to the exit of key UNIDO contributors such as Australia (1997), United Kingdom (2012), New Zealand (2013), France (2014), Belgium (2015), and Denmark (2016). Germany, who joined UNIDO in 1985, had threatened to pull out after the US’ exit but Mauricio de Maria y Campos, who was UNIDO director-general at the time, reportedly reminded Germany that German industries cooperating with UNIDO were receiving orders worth $10 million a year – “an amount more or less equivalent to Germany’s contribution to UNIDO” and which also demonstrated the kind of reciprocity the protection of the right to development of developing countries will engender for all nations, including developed countries. Interestingly, Germany opted to remain a member of UNIDO. In his so-called “Africa Initiative”, President Clinton emphasized the kind of economic reciprocity we are talking about when he noted that “although the US accounts for only 7% of African imports today, the continent already supports some 100,000 US jobs” (D+C, 1997). The UN Declaration on the Right to Development and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, if treated with the kind of global support – in terms of expedited policy implementation – accorded the ICCPR, will enhance the human rights of everyone across the world. The right to development is a human right. Implementing instruments such as UN Commission on Human Rights resolutions 1997/7 and 1997/10 (highlighted above) and similar resolutions passed by the Commission will enhance the improvement of the economic condition of billions of poor people across the world, most of whom reside in the developing countries. No human right, including the right to development, should be de-emphasized or ignored. As former UN Secretary-General, Kofi Annan, put it: One cannot pick and choose among human rights, ignoring some while insisting on others. Only as rights equally applied can they be rights universally accepted. Nor can they be applied selectively or relatively, or as a weapon with which to punish others. (UN Press Release, 1997) (Italics mine) Conclusion There is need to reiterate the importance of fairness in the application of the Universal Declaration and international human rights covenants within and amongst states. The Universal Declaration called itself “a common standard of achievement for all peoples and all nations.”122 The UN should ensure that human rights questions are settled “in the light of applicable international standards or international norms, or both” (UDHR, art. 29 (1)). As the Vienna Declaration (1993) has said: While the significance of national and regional particularities and various historical, cultural and religious backgrounds must be borne in mind, it is the duty of states, regardless of their political, economic and cultural systems, to promote and protect all human rights and fundamental freedoms. In other words, rights should remain rights but one should be sensitive to the peculiarities of the community where they are being exercised. References African Charter of Human and Peoples’ Rights, reprinted in Staff of the House Comm. on Foreign Affairs, Human Rights Doc.: Comp. of Doc. Pertaining to Human Rights 155 (1983). Alston, P. (1988). Making Space for New Human Rights: The Case of the Right to Development. Harvard Human Rights Yearbook, 1: 21–22. Brown, C. (ed.). (1985). With Friends Like These, The Americas Watch Report on Human Rights and US Policy in Latin America 28. Carrington, W.C. (1995). A Stimulant to Economic Growth in Nigeria. Crossroads, 1 (10), 3.) Charter of the United Nations, Chapter IX, Article 55 D+C International Journal, 5/1997, p. 33 Declaration on the Rights to Development, G.A. Res. 41/128, Annex. 41, UN GAOR Supp. (No. 53) at 186, UN Doc. A/41/53 (1986). Diller, J. M. (2012). Securing Dignity and Freedom through Human Rights: Article 22 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Leiden: Martinus Nijhorf Publishers. Fukuyama, F. (1988). The End of History. National Interest. Gray, J. (1994). The Hubris is Staggering. World Press Review, p.50. Hirschman, A. (1987). Rival Views of Market Society. Dialogue, 4, USIA, Washington DC, p.41. Huntington, S.P. (2011). The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order. Simon & Schuster. International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, G.A. Res. 2200, 21 UN GAOR Supp. (No. 16) 56 UN Doc. A/6316 (1966). International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, G.A. Res. 2200 (XVI), 21 UN GAOR Supp. (No. 16) 49 UN Doc. A/6316 (1966). Jack Donnelly, J. (1982). “Human Rights as Natural Rights,” Human Rights Quarterly, 4. Novak, M. (1987). Capitalism and Ethics: A Symposium. Dialogue, 4. 1987, USIA, Washington DC, p.35. Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, G.A. Res. 2200, 21 UN GAOR Supp. (No. 16) 59 UN Doc. A/6316 (1966) and Second Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, aiming at the abolition of the death penalty, Adopted and proclaimed by General Assembly resolution 44/128 of 15 December 1989. Rights of People to Peace, G.A. Res. 39/11, Annex. 39, UN GAOR Supp. (No. 51) at 22, UN Doc. A/39/51 (1984). Steiner, H.J. (1997). Do Human Rights Require a Particular Form of Democracy. Cairo, Egypt. Time (Special Issue), August 1, 1983. UN General Assembly. Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action, 12 July 1993, A/CONF.157/23, Part 1, paragraph 5. UN General Assembly, Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action, 12 July 1993, A/CONF.157/23, Part II, para. 3. United Nations Press Release SG/SM/6419 HR/4347 OBV/34 9 December 1997. Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). Preamble adopted by the United Nations General Assembly at its 183rd session on 10 December 1948 as Resolution 217 at the Palais de Chaillot in Paris, France. Universal Declaration of Human Rights, (UN Doc. A/811), art. 29 (1). US Department of State, Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 1982. Wriston, W.B. (1987). Dialogue, 4. 1987, USIA, Washington DC. * Taken from the author’s longer work, The Politics of Human Rights: A Discourse on the Theory and Practice of Human Rights.

|

|||||||||||||