Journal of Education, Humanities, Management and Social Sciences (JEHMSS), Vol. 1, No. 1, April-May 2023. https://klamidas.com/jehmss-v1n1-2023-03/ |

||||

|

Odinani: A Discourse in Philosophy of Culture Innocent C. Ngangah Abstract The main goal of this paper is to examine Odinani, the cultural belief system of Igbo people of south-eastern Nigeria. The spiritual, social and cosmic tenets of Odinani are felt through Omenani, the cultural practices this cultural philosophy generates. This paper is not about the latter; its scope is restricted to Odinani, the indigenous philosophical grail by which the Igbo people live, consciously or unconsciously. This study is an exploration of Odinani, its key components, analysed in terms of their epistemic, ontological and ethno-philosophical implications. A significant outcome of this study is the realization that, contrary to popular belief among a section of the Igbo elite and the media, Odinani is not a corpus of religious practices but the traditional belief system or worldview of the Igbo people. Keywords: philosophy of culture, Odinani, metaphysics, ontology, Igbo, eternalism, presentism

Odinani is the governing belief system of the traditional Igbo society. It can be defined as the cultural beliefs and spiritual blueprint of the people. The term “Odinani” means “inherent in the land”. Ani or ala (land) is the place where the monotheistic God, Chukwu (the Supreme Being), in His pantheistic manifestations, created and domiciled humans, animals, spirits and the elements. In Odinani is rooted the Igbo people’s worldview, and the rationale behind their worship of various deities, veneration of ancestors, as well as their masquerade phenomenon. It is important to distinguish, from the onset, Omenani (whose many manifestations are outside the scope of this paper) from Odinani, the belief system of the Igbo and our main focus here. Omenani (literally meaning “Practices of the land”) is the practical expression or dimension of Odinani, the Igbo cultural belief system. It is tempting to equate Omenani with Odinani; while both may seem synonymous, Omenani, strictly speaking, refers to the customary practices of the Igbo (such as their social organization, occupational inclinations, architecture, customary ceremonies, festivals, rituals, rites of passage, arts and craft, etc) whereas Odinani is the Igbo cultural belief system – its customs, mores, spiritual laws and cosmological ethos – that inspires and directs the above cultural practices. Simply put, Omenani is the practical manifestation or expression of Odinani. This paper is restricted to the philosophical examination of Odinani. Odinani as a holistic, interwoven, traditional belief system has inter-generationally been transmitted by oral tradition for hundreds of years. The custodians of Odinani, in pre-colonial times, were usually elderly men and exceptional women of integrity whom age, the gods of the land, and their long involvement with culture and tradition had given the privilege of serving as “tradition-bearers” (Ben-Amos, 1997, p. 802-3) and overseers. Being non-literate, they committed nothing to writing but faithfully passed on their traditional knowledge to successive generations largely by word of mouth and by their own acts of cultural observance which their mentees imbibed and practised. This is how Odinani has survived in Igbo land over the ages. Although a number of publications have documented some ethnographic information about the Igbo, very few have strictly centred their enquiries on Odinani. This paper is dedicated solely to Odinani, not merely to fill the gap but to properly position Odinani as the philosophic belief sysytem of the Igbo, and not merely its spiritual canon.

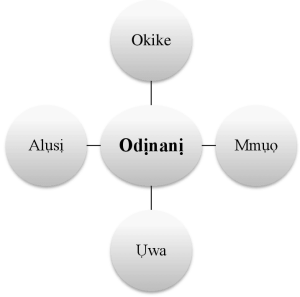

The Igbo people’s traditional belief-system is embodied in Odinani (tonally written and pronounced as ọ̀dị̀nànị̀ in Igbo). Odinani consists of the cultural, spiritual, and cosmic beliefs of the Igbo, and these three are interlinked and almost inseparable. However, for the purposes of this paper, we will try to discuss some aspects of these in separate sections. Ani or Ala (land) holds great spiritual significance for the Igbo people; hence, their entire belief system is symbolically tagged ọ̀dị̀nànị̀” (Isichei 1997, 246-247). Though Odinani literally means “inherent in the land”, its elements include extra-terrestrial forces. To understand the philosophical dimensions of Odinani, we shall discuss these elements in greater detail since the “philosophical categories” of the Igbo peoplde can be “identified through language, culture and metaphysical attributes of their lives” (Nkulu-N’Sengha, 2017). 2.1 Four Core Aspects of Odinani The four core aspects of the Igbo belief system consist of Okike (Creation), Alusi (Deities), Mmuo (Diverse spirits) and Uwa (the visible physical world). Since supernatural and natural forces are interlinked in Igbo cultural belief system, these four aspects are necessarily inter-connected. They can be graphically represented as follows:

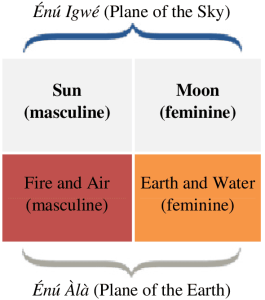

As you can see from the above tetracyclic belief structure, between Creation (Okike) and the created world (Ụwa) are deities (Alụsị) and diverse spirits (Mmụọ). We need to clarify the philosophical significance of each of these four core aspects of Odinani. Since the Igbo concept of existence is fundamentally anthropocentric, we will begin our discussion of these four aspects of Odinani with Ụwa, where created human beings physically dwell and round up with Okike. But, first, let us briefly discourse the cosmic qualities of Odinani. 2.2 The Cosmic Quartet of Odinani The Igbo cosmic quartet consists of Sun, Moon, Fire and Air, and Earth and water. According to traditional Igbo belief, the world (uwa) was created by Chukwu (the Supreme Being) who divided it into four paths, with two parts in the upper hemisphere and two paths in the lower hemisphere. The upper hemisphere is called énú ígwé. It consists of the sky (ígwé) and the rest of the heavenly bodies. The twin rulers of the upper hemisphere are the Sun (gendered masculine) and the Moon (gendered feminine). The lower hemisphere is called énú àlà. The lower hemisphere consists of two masculine elemental forces (fire and air) and two feminine elemental forces (earth and water). (See Figure 2)

These two hemispheres are governed by the Great Spirit (Chukwu) who dictates and moderates the activities of the quartets and ensures that they behave in characteristic ways in accordance with their assigned nature and seasons. The four cosmic paths and the two cosmic hemispheres are some of the reasons the numbers “4” and “2” are sacred to the Igbo.

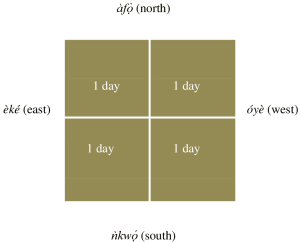

Uwa is not merely the physical world of people, animals, plants and the elements. In Odinani, it has material and immaterial, visible and invisible dimensions across time and space. In this section, we will examine the foundation and governance of Uwa and the metaphysical nature of its time and space. 3.1 Foundation and Governance of Uwa The foundation upon which Ụwa (the world) stands is anị or ala (land). Ala is physical and can be touched, farmed on, and built upon, but it is governed by a metaphysical being called Ala. She is revered as “the mother goddess of the earth, ruler of the underworld and goddess of fertility in all living things” (Praise 2018) and the goddess of morality and nemesis (Oraegbunam 2010). She is the consort of Amadioha (the Sky god), the latter ruling the heavens while she rules the earth. An imposing female figure and the python are some of the notable symbols of Ala. Ala is frequently invoked in Igbo land but nothing celebrates her towering place in the hall of Igbo pantheons better than Mbari house artistically built and dedicated to her. Although there are some which feature the carvings and sculptures of other gods (such as those of thunder and water) and some other beings, Mbari houses, typically constructed over a number of years, are mainly built to celebrate Ala, the most powerful deity of the Igbo. The art theorist and cultural philosopher, Herbert Cole, describes Mbari as “a merging of architecture, sculpture, bas relief, and painting”. Mbari, in physical and aesthetic terms, is a work of art, but it is essentially “a major offering to…the goddess of the very Earth upon which people walk, the source of food, plants and animals, and the main arbiter of tradition and moral law”. Notably, an Mbari house is never renovated after its official consecration by the spiritual elders of the community. No matter its state of dilapidation in subsequent years, it is a taboo for anyone to attempt to repair it, as it must be allowed to decay. So, beyond art and spirituality, Mbari is chiefly a philosophical construct, one that demonstrates that the end of every beginning is an inevitable death and that whatever gives life also contains the seed of death. Cole, in his “Mbari: Art as Process in Igboland”, highlights this ambivalence: Larger than life-size, Ala dominates the most accessible side of houses dedicated to her. Like other Igbo deities, she is ambivalent, considered good—she peels yams for her “children” (villagers) with the knife she holds aloft—and potentially evil—“dark Ala, who kills those who offend her.” …As Earth, she opens “to swallow people” in graves, the same Earth that provides yam, the main prestige food, plus other plant and animal life. Despite being an older woman of high status…she is a principal font of human, animal, and agricultural fertility and productivity. 3.2 Uwa: Metaphysics of Time and Space In his General Philosophy of Science: Focal Issues, Kuipers (2007) dissected various issues centred on “eternalism” (the opinion that all times are real) and “presentism” (the opinion that only present time is real) and the “cumulative” opinion that “all past and present events are real” (326). Uwa is construed in Odinani as a planetary realm in which time and space constitute an endless present-past-future continuum. Okagbue (2013) puts it this way: The Igbo universe is perceived as being made up of three planes of existence: the planes of the dead, the living, and the unborn. These planes correspond to the past, present, and future. Crucially, Igbo religious thought espouses an essential dualism based on a notion of mutual dependence and affectivity between spirit and matter. Every object or phenomenon has both spiritual and material aspects that are mutually complementary and dependent. Both time and space are seen in objective as well as in metaphysical terms, and this is why the days of the Igbo 4-day week have equivalents in the four cardinal points. In Igbo land, a week is called Izu and it has 4 days (ubochi ano). Each day is a spirit saluted by Eri, the sky-born progenitor of Nri Kingdom (a spiritual centre of the Igbo), when he went on a voyage of discovery beyond physical time and space. During that trip, he encountered four spirits – Eke, Oye, Afọ, Nkwọ – and named the days of the Igbo week after them (Isichei 1997, 247). Apart from the first two months which are serially named, the 13 months of the Igbo year are named after spirits or spirit-related ceremonies. Those ceremonies or events ensure that throughout the year, the tenets of Odinani are kept alive in the rituals and cultural acts of the people (Udeani 2007). In Fig. 3 below, we see another important quartet of Odinani. Ani or ala (the earth) is divided into four equal parts corresponding to the four cardinal points.

For the Igbo, Figure 3 represents a cosmic quartet with each “cardinal point” corresponding to a market day, as named and indicated in the diagram. There are four days between two same market days, thus corresponding to the Igbo belief that the world is divided into four parts and the four days symbolize these four parts (Ukaegbu 1991, 60).

The traditional Igbo person’s concept of being can be summarized in the singular word, ike (power). In Igbo ontology, a being, be it animate or inanimate, is that which has power, and that which has power exists. The power to exist is the proof of existence. It is the power a living person exhibits (the power to move, talk and do things) that makes him a being. And this power is not merely physical power, it includes spiritual power, and this is why the ancestors, though deaf, are deemed to be alive. They are alive because they can communicate with the living and have the power to protect their living kinsmen and women. Rivers, mountains, and the elements are all beings because without their inherent power they would not be in existence and can have no effect upon other beings, animate or inanimate. Though power is inherent in all beings, beings differ in the degree of power they possess and in their attributes and use of their power. The four core aspects of Odinani (see Fig. 2), with Alusi and Mmuo grouped together, reflect the three broad categories of beings in Igbo ontology, and these categories, in their order of power and influence, are as follows:

The Supreme Being is Chineke, about whom we will discuss later in this paper. Deific beings are comprised of alusi (deities) and mmuo (diverse spirits) while earthly beings, the most multifarious of the three broad categories, include human beings and all animate and inanimate, living and non-living, beings.

Deities (Alụsị) and diverse spirits (Mmụọ) constitute the second broad categories of beings in Igbo ontology. 1)eities are seen as powerful agents of the invisible God. They are venerated and their intervention is sought for all manner of spiritual, physical and material issues. The commonest deity in Igbo land is Ikenga, which literally means “power (ike) of going somewhere (nga)”. Ikenga symbolizes, for the Igbo person, the power of his life’s journey or the strength of his destiny. That is why it is kept by the traditional Igbo man as his personal god, as a conduit of the spiritual support of his ancestors, and as the strength of his right hand. Basden (1921), writing about the Igbo in the early 20th century, notes that ikenga occupies “the position of honour” in a typical Igbo compound. More than 40 years later, in the 1960s, Herbert Cole, re-echoes the significance of ikenga in the traditional Igbo person’s estimation and offers the following explanation: Ikenga, he notes, is “a male altar or shrine dedicated to a person’s right arm and hand, which are considered instrumental to his personal power and accomplishment.” Various types of ikenga are produced by master carvers and Cole describes some of their physical features as follows: Horns, as seen on…ikenga…are their diagnostic attribute. Many feature a seated warrior holding a knife in the right hand and a trophy head in the left, symbols, respectively, of decisive action and success. Others…show a horned head above a geometric, spool-like carving that stands for a body. Cole notes that the standing carving may be “a variant of full figure, warrior versions” of ikenga and may include “the image of a turtle who in folktales is a crafty trickster and…a symbol of wisdom”. An ikenga must be consecrated before it can work for its owner. It becomes spiritually activated when the blood of an animal, typically a fowl, is poured on it by the head of a man’s extended family or some other spiritual leader. Thereafter, a man sacrifices and prays to his ikenga daily or every four days. Mmuo or diverse spirits, in comparison with deities, are relatively less powerful spiritual beings. The inhabitants of the world (earthly beings) and diverse spirits constantly interact, though most people are not conscious of this interaction. Human beings living in the physical world interface with the Creator through deities and diverse spirits. The commonest deities and spirits among the Igbo are ancestral spirits and these are symbolized by mmanwu (masquerade). Masquerades, “in their ritualistic or theatrical functions” (Enekwe 2009), demonstrate the Igbo belief that there is an unbroken communion between the dead, the living and the unborn. Ancestral spirits refer to spirits of the ancestors of a given family, group of families or community. The ancestors, it is believed, though dead, hover in the spirit realm from where they oversee the affairs of living members of the extended family. Hence, prayers and libations are frequently offered to them. Every day in traditional Igbo settlements, as many times as families receive visitors and offer them kolanuts, the ancestors are called upon for provision, protection and guidance. Not all the clan’s dead are ancestors. To qualify as an ancestor, the dead must have lived a noble life worthy of emulation, a life credible enough to be respected by the living. As an informed commentator put it: Death is not a sufficient condition for becoming an ancestor. Only those who lived a full measure of life, cultivated moral values, and achieved social distinction attain this status. Ancestors are thought to reprimand those who neglect or breach the moral order by troubling the errant descendants with sickness or misfortune until restitution is made…serious illness is thus a moral dilemma as much as a biological crisis. (Britannica 2019) Ancestral veneration is rooted in the conviction of the Igbo that life is not terminated by death but continues thereafter in the realm of the spirit world. This is reinforced by the Igbo belief in reincarnation, that is, in the re-emergence of the dead, as a new-born baby, into the world of the living to live another life. A baby believed to be a reincarnation of a dead relative has the soul and some characteristic qualities of that dead person but otherwise is a baby in every other respect. Such a baby, however, may be given a curious name. If it is believed that it came as a reincarnation of either of its father’s dead parents, the baby may be called “Nnanna” (meaning, “The father of his father”) or “Nnenna” (meaning, “The mother of her father”), whichever is appropriate. Thus, the belief that the living and the unborn are inextricably connected to the dead is reinforced even in the naming of a new-born baby. Just as some Christians believe in the intercessory powers of saints, the Igbo, through ancestral worship, appease the ancestors and seek their intervention in the affairs of the living and the unborn (Elochukwu 2014, 184). For the traditional Igbo, existence is essentially cyclical across the realms of the dead, the living and the unborn. To conclude this section, it should be noted that there is no independent existence in the Igbo cultural belief system. Mortal and immortal beings are spiritually and cosmically connected. Although the High God (as Chukwu or Chineke) is not directly accessible to the Igbo traditional devotee, there are deities (alusi) and diverse spirits (mmụọ) through whom He can be reached. Every alusi is believed to be an incarnation of Chukwu who is considered too complex and too sacred for direct interaction with the ordinary traditional worshipper. So, a traditional priest called Dibia (a word which, depending on the context, also means seer, herbalist or healer) interfaces, using the medium of an alusi, to offer help to anyone in need of the deity’s spiritual intervention. Dibia has two main methods of mediating between the people and the deity, namely,

Okike or Creation is directly under the control of the Supreme Spirit, Chukwu or Chineke. Chukwu is invisible, immortal and inaccessible to mortal beings. As such, no altar or place of worship is built for him. In Igbo cultural belief system, God is popularly conceived in terms of His creative essence. And in this sense, the Igbo call Him Chineke, a closed compound word pronounced as a single unit of meaning but which, morphologically, is made up of three words, Chi (Supreme Force), nà (“and”) and ékè (“create” but, in this usage, “[one who] creates”). These two keywords are joined by the preposition nà (“and”) because neither Chi nor ékè is adequate enough as an independent noun to express the Igbo concept of “The Supreme Force who is Creator.” The duality in “Chi na eke” is a gendered one. Chineke as the progenitor of all things is conceived as embodying the timeless womb from where all things emerge. Hence, “Chi” is regarded as a masculine or father-figure force while “Eke” is perceived as a feminine, life-mothering, essence. In “Chi na eke” (compounded as Chineke), therefore, the masculinity and femininity of God, as conceptualized by the Igbo, is given singular expression. It should be noted that “Chi”, in the above contexts, is a corporate Being. But every individual has got his or her own “Chi” – an earth-bound personal god or guardian spirit which Chukwu assigns to every individual before their birth and which guides them throughout their lifetime. Every one’s destiny is a delicate balance between the dictates of their personal Chi and the resilience or feebleness of their own will. Hence the saying, “Onye kwe, Chi ya ekwe” (meaning, “If someone says yes, his or her Chi would say yes”). The duality in Chineke is, perhaps, the foundation for the pantheistic aspect of Igbo religion and the pantheon of gods spurned by this attribute. But in Odinani the Igbo religion is also monotheistic and God is primarily conceived as the Supreme Being before being a being of dual or multiple essences. In reflection of this monotheistic aspect of Igbo spirituality, God is called Chukwu (the Greatest Being or the Greatest Spirit). God as the Ultimate Chi is a singular Being distinguished from other Igbo conceptualizations of God by the superlative adjective, “ukwu” (meaning “greatest” or “highest”). Chukwu (Chi ukwu), therefore, is the timeless Supreme Being who, as Chineke, created all things. Chukwu is the Supreme Deity in Odinani as He is the Head of the pantheon of Igbo gods and the Igbo people believe that all things come from Him and that everything on earth, in heaven and the entirety of the spiritual world, is under His control (Onwuejeogwu 1975, 179). Identified as the Creator of the planets, principally the earth, Chukwu is also known as Chikeluwa (Chi kelu uwa), which means “God who created the earth.” As Chikeluwa, Chukwu is regarded by the Igbo as a solar (masculine) deity while Ani (land) is a feminine “being” who provides sustenance for human beings, animals and plants.

The major aspects and elements of Odinani explored in the foregoing have shown that Odinani is not just the spiritual belief system of the Igbo but their overall cultural and philosophical canon. All the cultural practices of the Igbo, spiritual and temporal, collectively called Omenani, and their overall perspectives on diverse aspects of life (family values, success drive, and burial rights) spring from the tenets of Odinani they have consciously or unconsciously imbibed. The view in some quarters, which has gained currency in some sections of the media, that Odinani is “the traditional spiritual practices of the Igbo people” needs to be revised. And if this paper has succeeded in raising awareness in this regard, it would have made a significant contribution. For long, the overall body of Igbo cultural beliefs has been taunted as the religious practices of the group. This is not true. And probably the confusion arises because, in the words of Okagbue (2013), “For the Igbo religion is a way of exploring, understanding and coming to terms wth both the natural (material) and the supernatural (spiritual) aspects of their world”. Odinani conceptually includes the material and spiritual aspects of the Igbo world. It is the Igbo worldview, not its religious practice. The Igbo religious practice is called “Ịgọ mmụọ” (worship/appeasement of or appeal to deities and diverse spirits). We conclude by re-asserting the position of this paper: Odinani is not a cultural practice (religious or otherwise) but a cultural belief system. Although it is not exactly what Nwala calls “Igbo Philosophy”, it has certain elements of Nwala’s characterization of “that philosophy”: That philosophy is unwritten and unsystematic. It was at the same time personalistic, highly ritualized and full of myths…It was pragmatic, meant to solve practical problems of food, security, peace and the general welfare of the community. It was thus non-systematic, less abstract in content, a bit conservative…Its ontology emphasized their belief in the spiritual nature of things and a type of cosmic harmony in which man and his actions are central, with supernatural powers and forces superintending. (Nwala 1985, 7-8) Odinani is the cultural belief system of the Igbo people that directs and informs their customary practices (spiritual and non-spiritual). Odinani is a system of traditional beliefs of the Igbos, their unwritten canon that instigates their cultural practices. Works Cited Basden, G.T. Among the Ibos of Nigeria. Seeley, Service and Co., 1921 Ben-Amos, Dan. “Tradition-Bearer”. In Green, Thomas (ed.). Folklore: An Encyclopedia of Beliefs, Customs, Tales, Music, and Art. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. 1997, pp. 802–03. Cole, Herbert M. “Igbo Art in Social Context”. https://africa.uima.uiowa.edu/topicessays/show/15?start=5 Cole, Herbert M. “Mbari: Art as Process in Igboland”. https://africa.uima.uiowa.edu/topic-essays/show/14 Elochukwu, Akuma-Kalu Njoku. Interface Between Igbo Theology and Christianity. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2014, p. 184. Enekwe, Ossie O. Igbo Masks: the Oneness of Ritual and Theatre, (Indiana University, 2009) Isichei, Elizabeth Allo, A History of African Societies to 1870, (Cambridge University Press Cambridge, UK. 1997), p. 512. Kuipers, Theo A.F. General Philosophy of Science: Focal Issues. North Holland. 2007, p. 326. Nkulu-N’Sengha, Mutombo. “Bantu Philosophy”. Encyclopædia Britannica, June 23, 2017. www.britannica.com/topic/Bantu-philosophy Nwala, T. Igbo Philosophy (Lagos: Lantern Books, 1985), pp. 7-8. Okagbue, Osita. African Theatres & Performances (Routledge, Oxford, 2013), p. 18 Onwuejeogwu, M.A (ed.). The Social Anthropology of Africa: An Introduction. Heinemann, 1975 Oraegbunam, Ikenga KE. “Crime and punishment in Igbo customary law: The challenge of Nigerian criminal jurisprudence.” OGIRISI: A New Journal of African Studies 7.1, 2010, 1-31. Praise, Billy, “The Gods and Goddesses of the Earth”. The Guardian, April 22, 2018 Udeani, Chibueze C. Inculturation as dialogue: Igbo culture and the message of Christ. Rodopi. 2007, pp. 28–29 Ukaegbu, Jọn Ọfọegbu. “Igbo Identity and Personality vis-à-vis Igbo Cultural Symbols”. Pontifical University of Salamanca, 1991, p. 60. www.britannica.com/topic/ancestor-worship. Retrieved October 12, 2019

|

||||